The authors provide a comprehensive and thought-provoking discussion of the multidisciplinary nature of caring for someone undergoing gender reassignment surgery.

In the last 50 years in the UK an estimated 130,000 people have changed their gender assigned at birth (assigned gender) to align it with their preferred gender [1]. The majority of healthcare providers within the field of plastic surgery will have knowingly or unknowingly encountered gender diverse persons in our professional or personal lives. The term ‘gender diverse’ is currently the most widely accepted term being used to encompass those who do not identify with their assigned gender and will be used throughout this article.

Please see Figure 1 for a glossary of terms commonly used in this field. This article provides an overview of the different members of the multidisciplinary team (MDT) who are likely to be involved in the care of a person who is undergoing gender affirmation surgery.

Figure1. Glossary

Assigned gender

The sex of a child is assigned at birth by medical or obstetric practitioners, or midwives. The child therefore is expected to take on the gender role of their assigned sex. This gender (role / identity) is referred to as the assigned gender.

Gender diverse persons

This is an umbrella term for individuals who identify as trans* and in some communities, intersex persons.

Gender dysphoria

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) defines gender dysphoria in adults as a “general descriptive term which refers to an individual’s affective / cognitive discontent with the assigned gender”. The incongruence between one’s experienced or expressed gender and primary (genitals) and / or secondary sexual characteristics (facial / body hair, fat distribution, Adam’s apple) commonly causes distress leading to functional impairment in psychosocial functioning. This is usually accompanied by a strong desire to be rid of sexual characteristics associated with one’s assigned gender and to obtain the sexual characteristics of the preferred gender.

LGBTQI+

One of many inclusive acronyms (e.g. LGBTQ*, LGBTQQIAAP) currently used by individuals or communities to define their gender and sexual identity. L=lesbian, G=gay, B=bisexual, T=trans*, Q=queer/questioning, I=intersex, +=asexual, pansexual, allies.

Non-binary

Individuals who do not identify exclusively as either male or female gender identities. It may be associated with other gender non-conforming identities such as genderqueer, genderfluid.

Preferred gender

The gender identity of a person is their preferred gender.

Trans*

An umbrella term for individuals who do not identify with their assigned gender. This includes transgender, transsexual and other non-binary gender identities. The term is slowly being supplanted by the term gender diverse person.

Transgender

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) definition is “the broad spectrum of individuals who transiently or persistently identify with a gender different from their natal gender”.

Transsexual

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) definition is “an individual who seeks, or has undergone, a social transition from male to female or female to male, which in many, but not all, cases also involves a somatic transition by cross-sex hormone treatment and genital surgery (sex reassignment surgery)”.

Background

Unless one has been shunning social media, popular culture or the news in the last decade, there seems to be an increase in society’s acknowledgement of the existence of gender diverse persons. With this acknowledgement comes some acceptance that this group faces inequalities in addressing their healthcare needs, including within the UK [2]. The rise in recognition of the diversity of gender identities is reflected in the recent increase in referrals to gender identity clinics [3] and thus, for gender affirmation surgery.

“The crux of gender dysphoria is distress caused by the incongruence of a person’s gender identity and their biological or assigned sex.”

Gender is arguably a social construct. It is the norms, roles and relationships that each society defines as characteristic of being male or female [4]. Gender is a separate entity from biological sex. The latter is determined by sex chromosomes and phenotype, e.g. expression of secondary sexual characteristics. The dichotomy of human sex and gender is being replaced by the concept of sex and gender being a continuum or spectrum. Disorders of sexual development demonstrate the diversity of sex. The term gender diverse (in the context of LGBTQI+ identities) encapsulates the colourful terms the community uses to express who they are in the spectrum of gender identity, such as transgender, trans*, non-binary, genderqueer, etc. This is a community that does not completely agree with the rigid binary structure of male or female gender identity that have been assigned to them by society.

The term gender is commonly used instead of sex, when biological sex is actually the intended meaning. This may be because gender seems a more polite word to many. In the context of gender dysphoria, a clear definition of gender and sex is essential. The crux of gender dysphoria is distress caused by the incongruence of a person’s gender identity and their biological or assigned sex.

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) Standards of Care

No article on the care of gender diverse persons would be complete without mentioning the Standards of Care (SOC) for the health of transsexual, transgender and gender nonconforming people. The current, seventh version, is a clinical guide that is based on current evidence and expert consensus [5]. It provides the basis for standardised, safe pathways to be adopted in different healthcare systems globally.

The treatment pathways consist of medical, surgical and ancillary interventions to align the body closer to the person’s gender identity. The process of realignment is referred to as the transition. This article will focus on the surgical aspect of transitioning.

Before surgery

Getting the diagnosis right

Gender identity clinics (GIC) in the UK, both the NHS and private providers, conform to the WPATH SOC. Two members of the GIC team must confirm the diagnosis. This can be a complex task. Patients with gender dysphoria experience higher rates of psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety. Gender-affirming medical intervention improves the prevalence of these disorders. The rates of other psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia are similar to the general population [6].

In the previous and current International Classification of Diseases (ICD) classifications, gender dysphoria is a mental disorder. ICD-11 will make a significant move of utilising the umbrella term of gender incongruence and reclassified as a sexual health condition [7]. The implications are to remove the stigma from the diagnosis and to allow greater access to healthcare for health systems that rely on codes for remuneration.

When the patient has expressed a desire for gender affirmation surgery (also known as gender reassignment surgery, gender realignment surgery, sex reassignment surgery) and they have fulfilled the relevant surgical criteria outlined in the SOC, the patient will be referred to the appropriate healthcare professional.

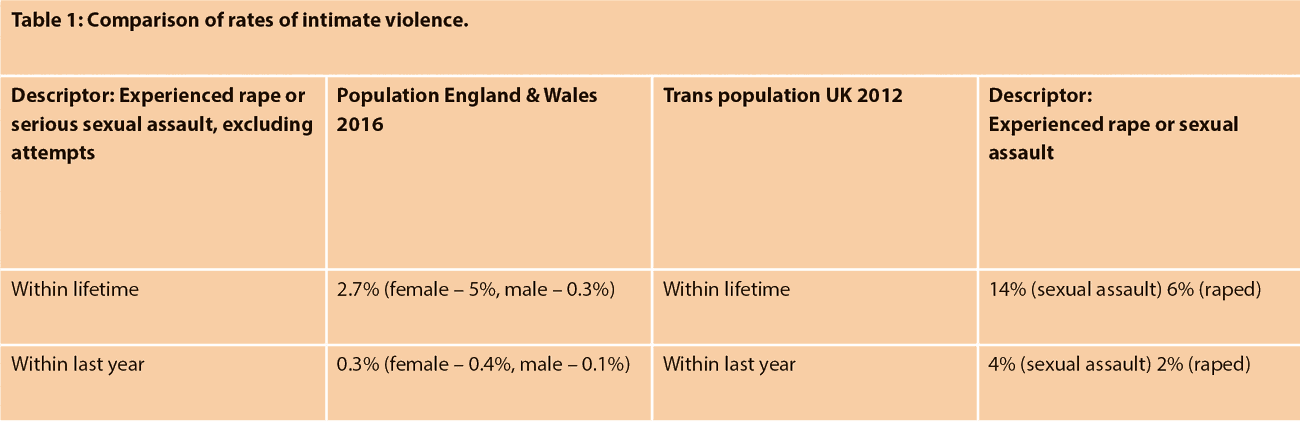

Healthcare professionals involved in optimising outcomes

Psychiatric and psychological evaluations and interventions may be required for a subset of patients prior to surgery. This is especially pertinent if other mental health problems, such as anxiety and depression which may or may not be related to their gender dysphoria, have been identified by the GIC. A significant number of gender diverse persons in the UK have experienced or know someone who has experienced harassment, physical assault and sexual assault, including rape, because of their gender variance [8]. There are no direct comparisons of the rates of intimate violence of gender diverse persons and the population. Table 1 attempts to compare the rates of sexual assault experienced by gender diverse persons and rates provided by the Office of National Statistics for the population of England and Wales in 2016 [9]. The different methodologies, definitions of sexual assault and statistical calculations have to be taken into account prior to drawing one’s own conclusions.

Surgery is a further stress factor in life. Managing existing mental health problems, and providing tools for coping and building resilience are essential in ensuring that the stress of undergoing surgery, managing its complications and the dissatisfaction of unmet expectations do not precipitate deterioration in the patient’s mental health.

Endocrinologists, physicians or GPs are generally needed to manage pre-existing co-morbidities, hormone replacement therapy and monitor for potential side-effects of hormonal therapy.

The infectious diseases team may be needed to treat blood borne virus (BBV) infections such as HIV and hepatitis. These infections are more prevalent in gender diverse persons as they tend to be socially isolated, vulnerable and therefore more likely to engage in substance abuse [8], or because of high-risk sexual behaviour to earn a living due to marginalisation from society [10]. By minimising the long-term damage to organs by BBVs, it may reduce the risk of general anaesthetic and wound healing complications. It also reduces the risk of exposure to the surgeon.

Laser hair removal services provided by accredited practitioners are essential in reducing unwanted hair from donor areas for genital reconstruction. Scrotal and perineal hair is removed prior to vaginoplasty or vulvoplasty. Forearm or thigh hair is removed prior to phalloplasty depending on the technique used. A hairy neophallus or neovagina is aesthetically displeasing. More importantly, hair within the neourethra can cause problems with urine flow and consequently infections and, less commonly, renal complications.

Urological assessment is indicated if patients are symptomatic of pathology within the urinary system, specifically bladder outlet obstruction, recurrent urinary infection and renal calculi. Any preoperative symptoms need to be managed as there will be significant alteration to urine flow postoperatively.

Gynaecological assessment is required as it may be necessary to perform hysterectomy and bilateral-salpingo oophorectomy if requested by the patient. This may be performed with a vaginectomy prior to phalloplasty as a combined or two-stage procedure. Legal gender change does not require medical or surgical sterilisation in the UK, although 22 other countries in Europe previously required sterilisation. A 2017 European Court of Human Rights ruling has stated that sterilisation was a violation of human rights, but laws in these countries are slow to change.

Adjuncts to improve the process of transition

Voice coaching is targeted at those who intend to sound more female especially on the telephone. Hormone replacement therapy does not significantly change the post pubertal vocal cords of those assigned male at birth. Voice coaching is sometimes utilised by those transitioning to a masculine gender identity prior to starting testosterone.

Wigs are commonly used by those with a feminine gender identity but exhibiting male pattern baldness. A good wigmaker ensures that the hair naturally blends in with the general appearance, rather than accentuate the attempt at feminising one’s appearance.

Gamete storage should be discussed prior to any irreversible surgery to remove gonadal tissue. Ideally, gamete retrieval and storage should be brought up by the GIC clinicians and referral offered prior to starting hormone treatment. Assisted conception units provide counselling and advice regarding gamete storage and assisted conception options. The NHS, since 2018, is to provide equal access for gender diverse persons to gamete retrieval and storage. There are different options available, depending on age (pre-pubertal, post-pubertal) and stage of transition (pre-transition, post-transition).

Surgery

Overview

Surgery can be classified into feminising or masculinising surgery. Surgery achieves what hormones, good make up and clothes cannot: permanent alteration of one’s physical appearance. Surgery generally has two aims: one, for others to perceive the patient as the intended gender at first glance, and two, for the patient themselves to feel comfortable in their own body. The roles of the different surgical specialties overlap and vary depending on geography and other factors. Therefore, for clarity and brevity, the discussions will be based on the surgical procedures rather than the individual specialty.

Feminising

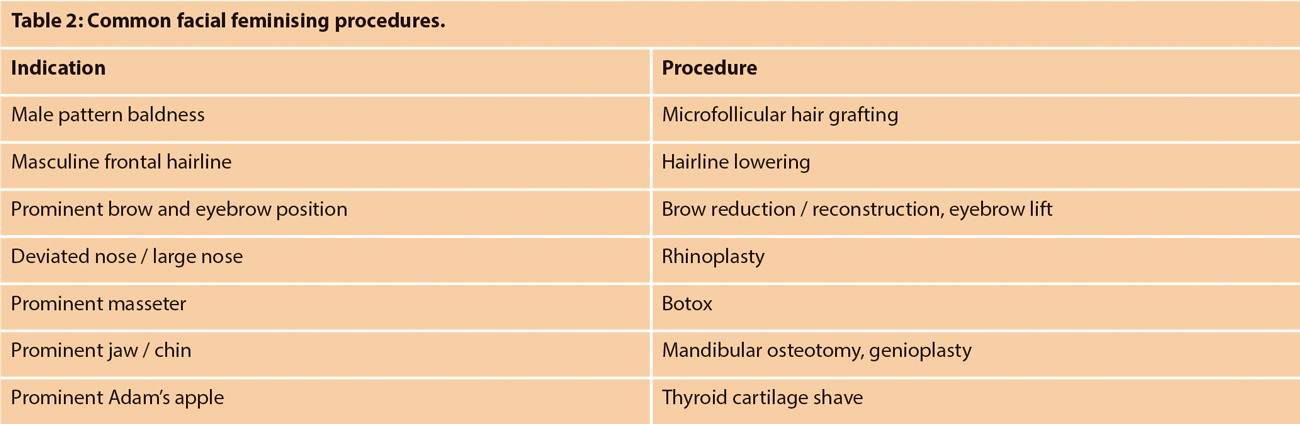

Facial feminising surgery is performed by maxillofacial, craniofacial, plastic and ENT surgeons. The aim is to reduce masculine facial features. Visual cues such as hairline, position of eyebrows, prominent brow, larger nose, jaw and chin, provide subtle signs of masculinity. Anecdotally, rhinoplasties for gender diverse persons are commonly performed to correct previously broken noses, as well as refining its appearance – this could perhaps allude to the frequency of physical assault experienced by gender diverse persons although, of course, there are different reasons for this injury occurring. Table 2 summarises the common procedures.

Speech modification is performed by ENT surgeons. It is performed when speech therapy fails to modify the pitch and resonance. There are multiple approaches, with no one more effective than others. The methods include cricothyroid approximation, laser vocal cord thinning, anterior vocal cord webbing, anterior partial laryngectomy and thyrohyoid elevation.

Chest feminisation is performed by plastic surgeons and less commonly, breast surgeons. It aims to increase the volume and shape of the breast to appear more feminine. Native males have larger chest walls than native females. These proportions do not change with hormone therapy, and thus the breasts tend to look proportionally smaller with a higher inframammary fold. Augmentation is achieved by breast implants and more recently, lipomodelling. Although the use of autologous flaps for chest feminisation has not been described in the literature, some centres have begun utilising local perforator flaps. The patients should be counselled, as with any breast implant procedure, about the risk of breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL). Patients should also be encouraged to self-examine and attend breast screening programmes, as their risk of developing breast cancer is similar to the general female population [11].

Genital feminising procedures are most commonly performed by urologists and / or plastic surgeons. Vulvoplasty creates the appearance of the external female genitalia, without the vaginal canal. This is suited for those who, due to existing co-morbidities, are not fit for a long anaesthetic procedure or those who do not intend to have penetrative sex. Vaginoplasty creates both the appearance of the external female genitalia and a vaginal canal. Colorectal surgeons harvest the sigmoid colon for sigmoid vaginoplasties, and repair any perforation of the rectum during the dissection of the neovaginal space.

Body sculpting is most commonly liposuction by plastic surgeons to create the appearance of a waist. Other, less common, procedures include trochanteric or buttock implants to create a more feminine silhouette.

Masculinising

Chest masculinising procedures are performed by plastic or general surgeons. The aim is to create a masculine appearing chest by removing breast tissue, removing the excess skin if required, and reducing and reshaping the nipple areolar complex. Unlike a therapeutic mastectomy, some breast tissue is left behind. The risk of breast cancer is similar to the general male population [11].

Genital masculinising procedures are performed by plastic surgeons and / or urologists. Depending on the aims of the patient, two different procedures may be offered. Metoidioplasty produces a micropenis with erogenous sensation and the ability to stand while voiding, but not to have penetrative sex. Phalloplasty results in a penis with reduced erogenous sensation, the ability to stand while voiding and likely penetrative sex. The procedures have a high risk of complications. Exploration of the urinary tract should be done by a urologist with experience of managing reconstructed urethras.

Other members of the MDT Anaesthetists aim to secure the airway without obstructing the surgical field with special consideration to facial feminising surgery. If previous vocal cord surgery has been performed, the anaesthetic team would exercise caution as there may be unpredictable scarring. Fibre optic intubation may be utilised to minimise complications.

Specialist nurses generally build a better rapport with patients as they will see the patient more often in the perioperative period. They offer invaluable support and advice to the patient. They are usually the key liaison healthcare professional.

Physiotherapists are perhaps not an obvious member of the team. In the postoperative period, patients who have undergone major reconstruction need rehabilitation to get them back to their previous level of mobility to reduce the risk of chest infection and thromboembolisms. Some specialist physiotherapists provide scar massage to counter the scarring, for example in phalloplasty donor sites.

Third sector organisations, such as formal and informal peer support groups, provide an essential social network to mitigate some of the social isolation and vulnerability experienced by gender diverse persons after their gender affirmation surgery. There is a level of unrealistic expectation that gender affirmation surgery would improve their well-being significantly. Patient-reported dissatisfaction with surgery was associated with poorer mental health and lack of support [12]. This is contrasted by satisfied patients, who had support from peers and their mental health team [13].

“Successful gender affirmation surgery relies on an integrated, multidisciplinary team.”

Conclusion

Successful gender affirmation surgery relies on an integrated, multidisciplinary team [14]. The MDT includes a reliable gender identity clinic, dedicated surgeons from various specialties, as well as support from other medical specialties and third sector organisations.

References

1. Barrett J. Gender dysphoria: assessment and management for non-specialists. BMJ 2017;357:j2866.

2. Whitehead B. Inequalities in access to healthcare for transgender patients. Health and Social Care 2017;2(1):63-76.

3. Joseph A, Cliffe C, Hillyard M, Majeed A. Gender identity and the management of the transgender patient: a guide for non-specialists. J R Soc Med 2017;110(4):144‑52.

4. World Health Organisation (WHO). Gender and Health. 2018.

5. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of Care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender nonconforming people. 7th version, 2011.

6. Dhejne C, Van Vlerken R, Heylens G, Arcelus J. Mental health and gender dysphoria: A review of the literature. Int Rev Psychiatry 2016;28(1):44-57.

7. World Health Organisation (WHO). ICD-11: Classifying disease to map the way we live and die, 2018.

8. McNeil J, Bailey L, Ellis S, et al. Trans mental health and emotional wellbeing study. UK; Scottish Transgender Alliance; 2012.

9. ONS. Focus on: Violent crime and sexual offences, year ending March 2016 – Appendix tables. [Excel spreadsheet] 2018. Available from:

https://www.ons.gov.uk/

peoplepopulationandcommunity

/crimeandjustice/datasets/

appendixtablesfocusonviolentcrime

andsexualoffences

[Last accessed December 2018].

10. Baral SD, Poteat T, Strömdahl S, et al. Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infectious Diseases 2013;13(3):214‑22.

11. Brown GR, Jones KT. Incidence of breast cancer in a cohort of 5,135 transgender veterans. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2015;149(1):191-8.

12. Dhejne C, Lichtenstein P, Boman M, et al. Long-term follow-up of transsexual persons undergoing sex reassignment surgery: cohort study in Sweden. PLoS ONE 2011;6(2):e16885.

13. De Cuypere G, Elaut E, Heylens G, et al. Long-term follow-up: psychosocial outcome of Belgian transsexuals after sex reassignment surgery. Sexologies 2006;15(2):126-33.

14. Monstrey S, Hoebeke P, Dhont M, et al. Surgical therapy in transsexual patients: a multi-disciplinary approach. Acta Chir Belg 2001;101(5):200-9.

Further reading

1. WPATH SOC

– www.wpath.org/

publications/soc

2. Intercollegiate Committee of the Royal College of Psychiatrists Good Practice Guidelines (adopted by England and Wales)

– https://doi.org/10.1080/

14681994.2014.883353

3. Scottish Gender Reassignment Protocol

– www.sehd.scot.nhs.uk/

mels/CEL2012_26.pdf

4. Salgado CJ, Monstrey SJ, Djordjevic ML. Gender Affirmation - Medical & Surgical Perspectives. New York, USA; Thieme; 2017.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME