What madness makes a human being perpetrate a crime that is so horrible, so evil that makes it a capital offense (in Bangladesh) even though the death involved is of a person who remains alive? The motivation behind an interpersonal assault with chemicals is often complex and poorly reported. Assaults with acid predominate due to easy availability, not to any understanding of the nature of the difference between acid and alkali.

Thank goodness, as the destruction of tissues with alkali involves the process of liquefaction necrosis with a more prolonged phase of deep tissue damage if the victim is not appropriately treated. Acids produce a coagulative necrosis and up to a point this can limit the penetration of the destructive fluid. Having seen the limitations of the conventional treatment for the acute injury I now advocate a very aggressive approach to the physical removal of the chemical load. This involves treating the acute burn as a surgical emergency.

P and P

The PRACTICE may vary

But

The PRINCIPLE remains…

Following a chemical assault injury:

• First aid – lavage, lavage, lavage

• First treatment – acute surgical removal of chemical and then continue

• Lavage, lavage, lavage.

The background and genesis of this approach has been described in a paper that was, interestingly, rejected by the editors of leading medical journals in the West but appeared in the Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery [1]. My co-author was Kauser Ahmed who had worked with the Acid Survivors Foundation in Bangladesh, a country with, globally, one of the highest incidences of acid assaults.

I am sure it was the word ‘pragmatic’ in the title that caused some discomfort in the worlds of those who desperately want to say they promote evidence based medicine (EBM). The reality though is that in burns care in particular, EBM is often a luxury, which our humanity and compassion regard as an indulgence. I have no hesitation in repeating what I have long taught:

“In many aspects of burns care we have neither the patients nor the patience to practice evidence based medicine.”

and

“Evolution of treatment is more often driven by experience that traditional strategies do not work, rather than evidence that new ones are better.”

I will not dwell on this further because I want to focus on the later stages of management, but as in all aspects of burns care, prevention is the best treatment. Primary prevention involves changes in social and cultural values together with legislation that must be enforced; secondary and tertiary prevention involves the emergency care outlined in our paper cited above. Quaternary prevention involves a degree of honesty and maturity that can neither be taught or learnt but can only be discovered through the most severe and critical self-analysis that unfortunately eludes too many surgeons. It is not a simple question of surgical ability. It is more a question of identifying the general and specific needs of a unique individual in the context of the limitation of the available facilities, resources and personnel to address those needs.

The assessment

The reason I talk about ‘renaissance’ rather than ‘reconstruction’ is that the goals are very different. Renaissance means re-birth. The goal is to help a person start a new life, which is not based on the physical appearance of the old one. Going back to the motivation of the acid assaults, these can be broadly defined as the three Ls: land, love and loans. In each case the perpetrator does not want the victim to physically die (too quick), they want them to suffer the death of their identity and social acceptance, and they want that suffering to be lifelong. Reconstruction would attempt to restore the pre-injury appearance and lifestyle but until and unless we unlock the secrets of tissue regeneration we will never be able to re-create the pre-injury form and function.

Renaissance is far more subtle in terms of the holistic implications. And I say this having been involved in post-burn facial reconstruction for rather a long time! Yes, the face is a key feature of the post acid attack surgical challenge. In a small review of cases we published some time ago, over 90% of acid attack victims have facial involvement. Destruction of identity is, after all, one of the key motivations of the attack.

It is apparent, though, that we are at a very rudimentary phase of aesthetic analysis and this will become more obvious as we become more critical, more objective and more astute in assessing the outcome of our interventions. There is an ‘ambience of aesthetics’ which can be illustrated by the way one face can become many faces by altering lighting, sound, mood and emotion. The effects of lighting are revealed in an interesting video ‘sparkles and wine’ (http://www.nachoguzman.net/gallery-category/video/#sparkles-and-wine).

So how do we make an assessment of a scarred and distorted face in an emotionally scarred and deeply injured individual? How do we begin to see their world through their eyes, which now may be less able to see, as we see, because of corneal scar? How do we begin to make an assessment of a person who has already received multiple operations (elsewhere) and remains unhappy, incomplete and despondent?

I pose these questions without being able to provide detailed answers, at this time. One of the quests of PMFA News will be to further the exploration of a more holistic aesthetic analysis. It is in that spirit that I share a few cases, some good, some bad, with an open invitation for critical comment.

Case 1

Figure 1.

See Figure 1. This young lady was the most beautiful girl in her village. She was pursued by an older man but rejected his advances. The response was “If I cannot have you, no-one will have you.” She was attacked in a rural environment and did not receive any acute care. She presented with established scarring with functional incapacity and obvious disfigurement; eyes, nose, mouth, neck.

There have been attempts to classify the effects of scarring by looking at the dysfunction of the anatomy; contractures affecting joints can be measured in terms of the restriction of range of motion, mouth opening can be measured in millimetres as can lack of eye closure. But these are objective, external and may not relate to the more subjective, internalised concerns of the patient. This young lady had already ‘died’ as an ‘object of beauty’. She would cover her head if she went out of her house. Her major concern, or the one which she was able to express, was her inability to retain fluids in her mouth, the difficulty of eating with impaired oral continence. The solution was ‘easy’: release the contracture, restore the anatomy, assess the soft-tissue defect and fill it. But then the practical reality of logistics, process and outcome make the ‘easy’ solution of the novitiate surgeon an example of folly. I met this young lady some years ago in Cambodia whilst on a short surgical ‘mission’ from the comforts and sophistication of Hong Kong. I would not do now what I did then. A pedicled Latissimus dorsi flap from the unscarred back inserted into the right side of the neck allowed the tissues to be advanced and the mouth to close. I envisaged a subsequent division of the pedicle and resurfacing of the left side of the neck. I had not even begun to consider the implications of staged surgery in an environment where a single surgical intervention is an unachievable dream for many patients with acquired deformities and disabilities.

Case 2

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

What about Madam T (Figure 2), a wonderful woman from Guangdong province in the south of China who had urged her younger sister to break up a relationship with a ‘bad’ man? The result was the ex-boyfriend decided to punish the older sister by throwing acid in her face. Madam T came to Hong Kong, blind and scarred to seek ‘reconstruction’.

This was a completely new challenge for me, as I had not previously thought about how you discuss the realistic expectations of aesthetic surgery in a patient who cannot see. This opens up yet another unexplored dimension of aesthetic analysis, the tactile assessment. Madam T was, by training and occupation, a beautician. From years of treating clients with facial massage she had learnt to ‘read’ faces with her fingers. She could assess the symmetry of a face by feeling the shape, she could assess the plasticity of the tissues, the location and density of subcutaneous fat and she could correlate what she could feel with what she could see.

A scalp tissue expander allowed advancement of the anterior hairline and resurfacing of the forehead; nasal reconstruction was a staged procedure with a free style perforator flap from the medial thigh; eyebrows were created with composite grafts and a visiting surgeon from Italy performed an osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis in the left eye.

The procedures were undertaken over a number of years as she had relocated to Hong Kong to spare her husband and daughter the distress of seeing her. She was a very intelligent and sensitive lady and whilst she expressed gratitude and optimism when she visited the hospital she was quietly dying inside. Our focus had been too much on the tangible, physical, appearance and with the lack of trained and experienced psychological support we did not address the holistic renaissance I now advocate. I present her as one of my profound failures because she ultimately jumped to her death from her 14th floor apartment five years after the assault.

I pondered on the mechanism of aesthetic assessment of the blind person in an editorial I wrote some six years ago, but I have not made much progress since [2].

After her death I was given a copy of a picture taken at her wedding (Figure 3). This filled me with a sense of sadness as I imagined her lying alone each night, searching with her sensitive fingertips for the face she once knew.

Case 3

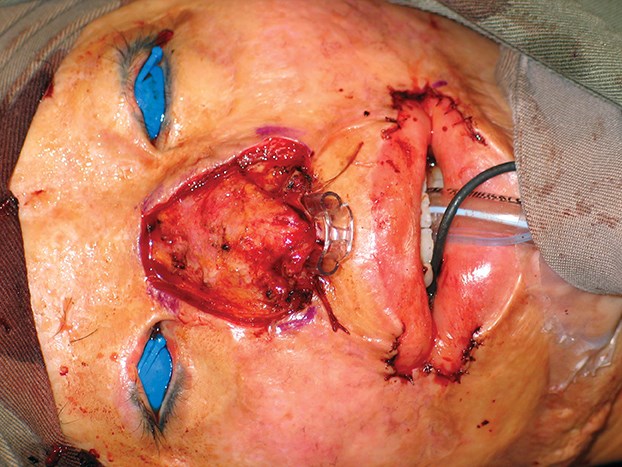

Figure 4.

Madam H was another victim of an acid assault from Southern China (Figure 4). I share her case to underline the economy of truth that has become ingrained in too many modern plastic surgeons. Microvascular free tissue transfer has opened up many new reconstructive opportunities but it does not necessarily make the totality of the surgery easier, better or quicker. Let me explain.

Madam H presented with scarring and functional impairment of both hands and her face; a not unusual distribution where the victim has tried to protect himself or herself by covering the face with the hands.

The burns are different in terms of the depth and the tissue response and again this adds to the challenge of assessing the dynamic aesthetics of the post-burn face. Ah, yes! I must mention that this is not a ‘post-burn face’ we are looking at, but a patient with scars on the hands and the face; she has deformity and disability. But deformity does not necessarily produce disability; attitude, education, training can all optimise the function of a deformed part, perhaps enhance the form and function of an opposing or balancing part and the result is ‘normal’ ability. Independence. Self-caring.

There are several different routes, involving different costs, in terms of time and chance and risk. And you cannot really express any of this unless you enter the needs, the wishes, the desires, the hopes and the fears of the patient. It takes time, and often a multidisciplinary, multi-professional approach for the patient to feel confident, comfortable, or at times desperate enough to consent to surgery. It is a big responsibility to take a person’s life in your hands as a surgeon. If renaissance is true, if it is real, if it happens; then you are the mother and the father of the child.

It is a big responsibility and I am not talking here about routine scar release in the post-burn limb for example. No. I am talking about those who have had their identity stolen by scarring that deforms and disfigures and destroys, forever, a life defined by that face. This is the death. Even in the midst of the closest families there will be this death. Because it is a death within. I am using some rather florid imagery to try to convey the sense of responsibility you must commit if you want to care for such patients.

So what about Madam H? Flaps and grafts for the hand releases and then a session on the face. And another. And another. This is the reality of post-assault burn facial surgery. And once the surgery is over, the aesthetic medicine specialist will come in with the fine-tuning of the aesthetic appearance, mainly in terms of contour and expression. And then the beauty therapists will work on creating and maintaining a healthy and viable skin which in turn the beauticians will use as the canvas for the applications of cosmetics to cover and conceal the flaws and enhance the residual features of beauty.

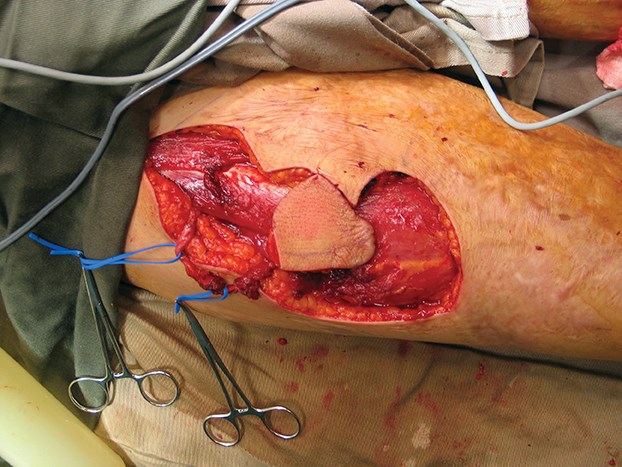

It takes time, it takes commitment and it takes a therapeutic relationship that transcends the limitations of a single profession or specialty. And so we follow Madam H as the microstomia is treated and a new nose is fashioned from a free style free flap from the anterior thigh (Figure 5).

Figure 5a.

Figure 5b.

Figure 5c.

Figure 5d.

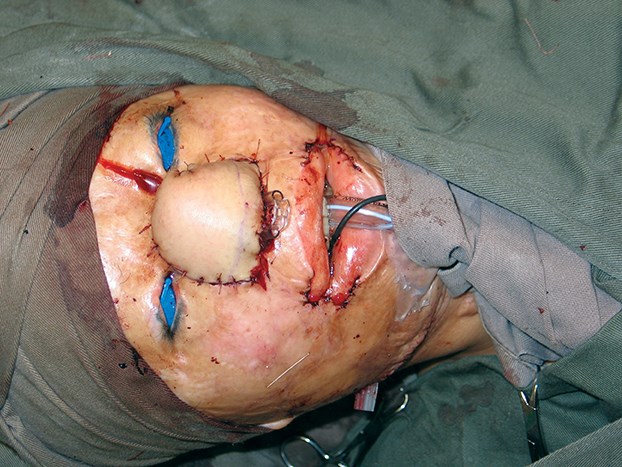

This last picture in the series always paves a way to an interesting discussion amongst medical students as I proudly put up Figure 6 and ask for their comments.

Figure 6.

I know I have some honest students when they express some shock, even horror, at the result. This opens up the discussion to reviewing what has happened and what is going to happen. This is, again, a very important part of the counseling of the patient as it is important to keep them focused on the process of ‘renaissance’. I liken this to the work of the potter who takes moist clay from a drum and throws it on the spinning wheel. This is stage one and now the artistry begins, as the transformation begins to fashion from that ‘lump of clay’ to a work of art. This does not happen quickly or in one go. Time and patience are needed and once the basic contours are right the facial resurfacing begins with dermabrasion and split thickness sheet grafting.

The resurfacing is done, beginning with the lower third of the face and then the middle third and all the while taking care of those little irritations such as milia and overgrafts (Figure 7). The journey is long but over time a new face can be built and a new person can emerge (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Figure 8.

What are the aesthetic changes in these faces? I should mention that the two rather out of focus ones were not my originals but they have both been given to me by Madam H with her consent to use them in any way that can help. And so I focus on outcome and time, and patience. And I wonder who Madam H sees in the face in the mirror. Does she move her cheek to see the response? Is it her or is it someone else? Is she happy with progress? Actually yes, and for me she represents a happiness in medicine, in the art and craft of plastic surgery. We will continue with a little bit of laser, some microdermabrasion, microfillers, etc. And Madam H will regain her confidence, her independence, her life. There will always be a special relationship between a patient and ‘their’ surgeon and it is important to remember that. The deserving surgeon will be put on a pedestal, and with that recognition goes a responsibility. And in some ways that responsibility can be summed up in the word ‘recognition’. Surgeons may have many patients but each patient has only got one surgeon. They will never forget you and you must never forget them. That is the responsibility (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

In conclusion

Before I draw this brief glimpse into the world of post-burn aesthetics to a close I must share one last ‘tension’ with you and that is the ongoing tension between psycho-social rehabilitation on one side and composite facial transplantation on the other, with regeneration pulling in yet another direction.

Facial transplantation is in the very early stages of assessment in terms of outcomes. Four recipients of facial transplants have died. Grumbling chronic inflammatory reactions related to the ongoing immunological interactions between the graft and the host have distorted the tissues of other recipients with fibrosis. I could have been more negative about facial transplantation if I had written this morning. But a free paper in Pacific Coffee, the China Daily, Hong Kong Edition, contained a syndicated article from the New York Times which shouted out to be read. The headline was ‘Ghastly crime, a new face’. I wondered who on earth was in charge of approving that one? It was the story of Carmen Tarleton who had a very destructive chemical poured on her face one night by her estranged husband. Some years later she received a facial transplant in Boston performed by Dr Pomohac’s team and the article, more appropriately subtitled ‘A crime victim gets a new face’, gives an account of the ongoing processes of psychological re-adjustment [3]. There is also a video that can be viewed online:

http://www.nytimes.com/

video/us/100000002494852/

a-face-in-progress.html

I will leave regeneration for another time and move on quickly to psycho-social rehabilitation. Nobody understands the importance of this more than James Partridge, the founder of the charity Changing Faces [4]. James wrote an autobiography entitled Changing Faces: the Challenge of Facial Disfigurement. The following could be a brief plot synopsis:

‘Through a deeply personal journey, a severely burned university student rediscovers his ‘face’ in the community and in the process gains a wife and a new life.’

And what an amazing life it has been. Figure 10 was taken in South Africa some years ago. The lady sitting next to James was, in the times of Apartheid, branded a terrorist by some, a freedom fighter by others. She has gained great respect from her fight and now acts as a community liaison officer between the impoverished inhabitants of the Cape Flats and the white health care workers in the local hospitals. But what emerged from the dinner table discussion that night was that Apartheid, at least a form of it, still exists. But now it is not colour but aesthetic appearance that separates people.

Figure 10.

References

1. Burd A, Kauser A. The acute management of acid assault burns: a pragmatic approach. Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery 2010;43(1):29-33.

2. Burd A. Plastic surgery, body image and the blind. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery 2007;60:1273-6.

3. For victim of ghastly crime, a new face, a new beginning. The New York Times. October 26, 2013. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/26/

us/for-victim-of-ghastly-crime

-a-new-face-a-new-beginning.html?_r=0

4. Changing Faces:

https://www.changingfaces.org.uk/Home

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.

TAKE HOME MESSAGE

-

The aim of many who assault with acid is to punish another by a lifelong imprisonment in a prison of scar. A scar that deforms, disables and destroys a person’s identity.

-

Urgent and appropriate first aid can reduce the effects of the chemical destruction but inevitably there will be those victims whose facial destruction is so great that there can be no prospect of restoring the appearance to the pre-injury state.

-

Embarking upon the surgical and psychological rehabilitation of such patients is a big responsibility and should not be undertaken lightly.

-

To be part of a rebirth which gives rise to a new person is a very complex process which requires not only a comprehensive range of surgical skills but also a profound understanding of the human psyche; how much it can be harnessed to give a positive outcome and how much it can be challenged to be a key driver of the process.

-

Specific techniques can be addressed in the future but this introductory article outlines the general approach.