Dr Nikolaos Metatoxos has written an excellent article ‘How to establish a successful practice in aesthetic medicine’, which looks at the business of aesthetic medicine and underlines some very important ethical issues. When comparing hospital doctors and aesthetic medicine practitioners Nikolaos makes this very pertinent observation: hospital doctors want their patients to get better and not return, aesthetic medicine practitioners want their patients to return “as often as possible.” He then asks, why would patients return?

This is a very important question to ask for anyone who wants to make a business out of aesthetic medicine. It is good to hear people who will speak up and say that “results are rewarded” because this is the philosophy of the outcome-based medicine school. I am using the term ‘school’ to designate a ‘school of thought’, not an institution. In some respects it is not surprising to read that service is valued as much as the medical procedure. From a technical point of view the medical procedures have limited scope for variation, certainly limited when compared to the abundant variations possible when considering the services associated with the delivery of the procedures.

The figures quoted from the American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery also make a very telling point about the divergence of aesthetic medicine from aesthetic / plastic surgery. The reaction to this new reality exposes the true nature of those who have at some point in their careers elected to pursue the specialty of plastic surgery in their clinical training. It is apparent that for some the specialty was an end in itself; the challenge of creating a better quality of life for those injured or left with post surgical oncological defects or born with anomalous anatomy or function. The challenge when met with a positive outcome for the patients was the source of professional fulfilment and satisfaction. For others, though, the specialty was a means to an end. And the end was personal wealth creation. Whilst the former have not been affected so much with the recent trends in aesthetic medicine, those who are seeking more tangible, financial rewards, are having to make some difficult choices. Indeed, the choices can ultimately redefine the specialty of plastic surgery.

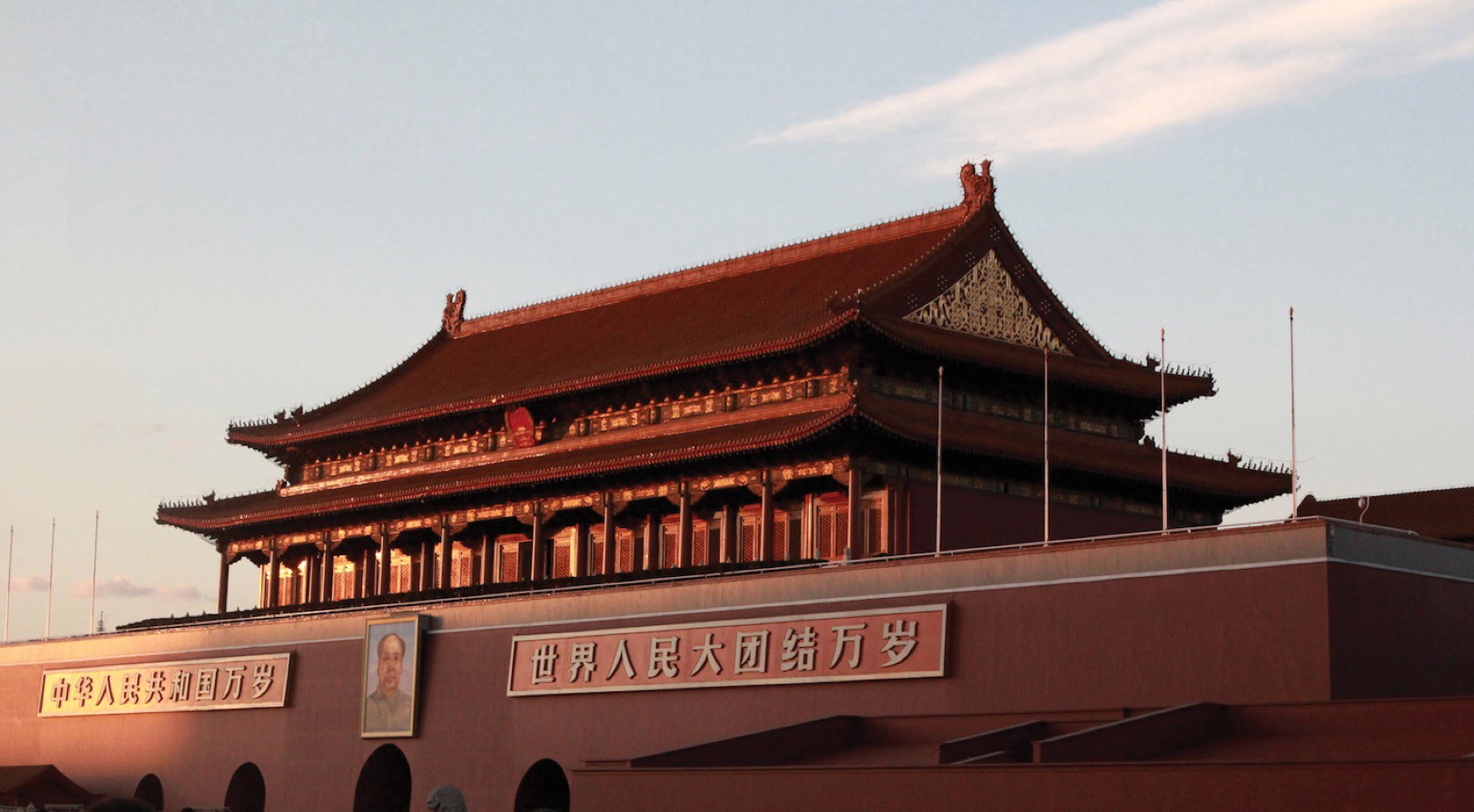

This has become a major issue in Hong Kong and I was recently invited to Beijing to talk about the current status of plastic surgery in Hong Kong. The invitation came from Dr Wang who is the Head of the Division of Plastic Surgery at the Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH). The occasion was the opening ceremony of the Plastic and Aesthetic Surgery Division of the Cross-Straits Medicine Exchange Association and the China Plastic and Aesthetic Surgery Summit. PUMCH is a remarkable institution and provides an exceptional level of high quality care across the full spectrum of acute medicine. In addition, however, the plastic surgery division provides a medical aesthetic service, which also serves to give hands-on training in the non-surgical procedures to the plastic surgery residents. This is a model of service delivery, which is possible when hospitals are run as business ventures, albeit within the scope of a generally public service.

The situation in Hong Kong is quite different and the four year long training programme based in the public Hospital Authority (HA) system contains no such exposure to the non-surgical or even the surgical ‘cosmetic’ procedures. Also, for historical reasons plastic surgery in Hong Kong does not include hand surgery or lower limb trauma as, for example, in the British model of training. The result then is a rather idiosyncratic specialist who has to make some tough decisions about whether to remain as a plastic surgeon in the public sector or transform into a part-time plastic surgeon, part-time aesthetic medicine practitioner in the private sector. There are those who have made the transition very effectively and have diligently pursued the extra training necessary to provide an excellent service in aesthetic medicine.

There are others though who have tried to control the market through making claims that are just not true; for example that specialists in plastic surgery are the only specialists trained in cosmetic surgical procedures. Such a statement has two effects, one is to drive legislation that restricts the provision of certain cosmetic procedures to those with specialist status and the other is to convey to the public that only specialists have the training and the competences to deliver the outcomes patients desire.

The problem arises when such a perspective is formally detailed in a professional society website. This website links specialist status to training and competence but omits two very important points: just under half of the specialist plastic surgeons in Hong Kong have not been through a formal training programme in plastic surgery, neither have they undergone any assessment of their surgical and clinical competence in plastic surgery; the second point being that even those who have undergone the formal training programme and assessment have little or no exposure to cosmetic procedures by the time they can officially call themselves ‘specialists’.

In Hong Kong, as in other parts of the world, it is an offense for ‘traders’ to give false descriptions of their training, expertise and service. However, the Fair Trade Description Ordinance and its amendments list a number of exempt people and these include medical practitioners. The reason is that medical practitioners are subject to the professional control and regulation of the Medical Council of Hong Kong (MCHK) and it is up to the MCHK to enforce the spirit of the law, as well as the law within the medical profession. The problem is that the MCHK is a party to the confusion over specialist status. This relates to the establishment of the Hong Kong Academy of Medicine (HKAM) in 1993. This was a time when Hong Kong was looking to the post-colonial future and wanting to protect the local medical profession from being overrun by doctors from Mainland China. The HKAM is the institution to affirm specialist status and works with the Academy colleges to maintain standards and foster a mature, collaborative profession that works in the best interests of the people of Hong Kong. Without being flippant the Hong Kong Academy of Medicine Ordinance Chapter 419 contains an aspirational list of aims and objectives that reflects an idealistic rather than a realistic world.

In order for such an Academy to flourish it needed support; fellows and subscriptions. Hence the addition of Bylaw 16, which set a very low admission criteria for the founding fellows and was rescinded five years later. For some it was a ‘grandfather’ clause, but for others it was a shortcut to specialist status. This was the case for the speciality of plastic surgery that was not formally recognised in Hong Kong before 1993. So the founding fellows of the Plastic Surgery Board within the College of Surgeons of Hong Kong (CSHK) were an eclectic mix of general surgeons, orthopaedic surgeons, head and neck surgeons, who were united in one goal and that was to be called plastic surgeons. It was this group that defined the specialty without realising that it was an idiosyncratic mix that could find no partners in the wider world, e.g. plastic surgery in Hong Kong is the only surgical specialty that does not have a conjoint examination with the Edinburgh College of Surgeons.

So what could I say when I went to Beijing? First let me put in perspective my relationship with PUMCH. My connection goes back a long way and certainly I was visiting Beijing long before I took up post in Hong Kong. I was a Visiting Professor at PUMCH and was delighted to invite Professor Qiao Qun to Hong Kong and explore a residence exchange programme. When I was invited to Beijing in December of last year it was on the basis of a personal invitation and not an official invitation through virtue of any position in Hong Kong. It was on that basis that I accepted the invitation, but gave a talk that was not expected. Plastic surgery in Hong Kong is in a state of crisis. The Chinese ideograms to depict the word ‘crisis’ consist of two concepts, danger and opportunity. I explained that the danger is that the current projection for plastic surgery in Hong Kong is oblivion. It remains caught up in a time warp determined by the self-interest of a few who want to maintain an exclusive status based on the name of the specialty rather than the service, the training and the competences associated with the name.

An indication of this comes from the professional website, which quite falsely links the title of specialist with completion of training and formal assessment. Whilst this is true now it is not true of the founding fellows and I can state as a fact there are founding fellows who would not even make the training programme today let alone complete such a programme. That would not be a major problem if such fellows kept quietly in the background. Unfortunately that is not the case and it is profoundly disappointing for me to see a noble specialty being brought into disrepute by those who are plastic surgeons in name only. The background and history are complex, but that is the nature of life and there comes a time when the complexity is impossible to unravel and the best recourse is to cut it out and start again.

This is what I indicated in Beijing. The current political position of Hong Kong is succinctly described as one country, two systems (for a limited period). As such there is a limited period in which Hong Kong can maintain the status quo with regard to professional regulation and control. I am not talking about government politics here, as that would be unwise. No, it is a matter of looking forward to keep plastic surgery alive for those who see the specialty as an end and not a means to an end. In that respect I suggested that we should see how plastic surgery in Hong Kong can align itself with the Mainland. That will require some drastic changes in attitude but also flexibility in training and rotations through hospitals that deliver aesthetic medicine as part of the specialty. This would be one way to address the evolving nature of the relationship between the more traditional (reconstructive) plastic surgery and emerging specialty of aesthetic medicine. We have to accept that the world is changing at an unprecedented pace and plastic surgery is no exception. If we embrace change we will survive but if we resist change we will not survive. The crisis in plastic surgery is not unique to Hong Kong but what is happening in Hong Kong is a salutary lesson from which others can learn.

In Hong Kong there are attempts to limit who can perform certain procedures, not based on ability or competence but on the title of the practitioner. Those who have the title, not through merit, but through a historical anomaly, most actively support this move. The title in question is ‘Specialist in Plastic Surgery’. The MCHK, the HKAM and the CSHK are all aware that there are those specialists who have the title not through training and objective assessment but through virtual self-selection. The problem arises when such specialists claim competences they do not have and then proceed to undertake procedures outwith their expertise. In the UK the concept of ‘revalidation’ was proposed to address such concerns but this regulatory concept, whilst sounding excellent in theory is proving far more difficult to establish in practice.

So what is the solution? Regulation and control or a ‘free market’? Both are open to abuse, but the ‘free market’ is more responsive to changes in the consumer base. Outcome-based medicine is the way of the future and, when I use the word ‘outcome’ I am considering the patient outcome, not the financial outcome for the practitioner. As such, taking a patient perspective, I would like to see enough regulation and control to ensure products, materials and facilities are safe but ultimately who performs any procedure should be based on the skills and competences that produce the best outcomes. Again, taking a patient perspective, surely I decide what are the best outcomes, not some professional regulatory body with all of those inherent ‘conflicts of interest’? Put it another way: a specialist is only a specialist if they are special but you do not need to be a specialist to be special. For the patient it is far more important for the practitioner to be special than to be a specialist.

For a response by Lee Seng Khoo to this article, please see:

IN RESPONSE TO: Plastic surgery and aesthetic medicine: specialties and specialists

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME