“It is an interesting biological fact that all of us have, in our veins the exact same percentage of salt in our blood that exists in the ocean, and, therefore, we have salt in our blood, in our sweat, in our tears. We are tied to the ocean. And when we go back to the sea, whether it is to sail or to watch it we are going back from whence we came.”

JF Kennedy, 1962

The gentle slide into professional senescence after a quarter century of professional post-graduate efforts was blown out of the water, as it were, by a somewhat unexpected ‘life event’. After, in retrospect, a gratifyingly short period of aimless flailing I recalled decades previously my father passing on Sir Robin Knox-Johnston’s book A World Of My Own [1].

Post-FRCS Part 2 euphoria saw me interviewed by the great man himself in a stately home somewhere in Leicestershire. Delight at being accepted as crew for the inaugural Clipper Round the World Yacht Race – for amateur sailors only – in 1995-96 was, however, swiftly curtailed. The terse “you either wish to be a surgeon or **** about on a boat for a year” was my then Professor’s pithy response. After due reflection I accepted his proffered Lecturership in Surgery. A long-held enthusiasm for teaching meant it was no great hardship and led to other useful things, not least a Master of Surgery and patent for something of potential therapeutic benefit in breast oncology.

My second interview, on this occasion at Clipper’s base in Gosport, saw selection as crew for the 2017-18 race. It should be noted the itinerancy of a career in plastic surgery had precluded progress in sailing endeavours other than the all-too-infrequent weekend jaunt along east coast rivers, primarily as a prelude to socialising. As with surgery, things had progressed in the interim and four solid weeks of training was now mandated, soberingly due to the loss of two crew from the 2015-16 edition.

Being a product of what we would probably now view as the ‘old fashioned’ surgical apprenticeship model, I had orbited a small, but influential handful of forward-thinking mentors who had selflessly imparted their accumulated wisdom. Over the years this had nurtured my interest in personal development, along with the evolution from an IQ (intelligence quotient) to an EQ (emotional quotient) perspective. The latter being a measure of ability to understand, use and manage own emotions in positive ways to ameliorate stress, communicate effectively, empathise with others, overcome challenges and defuse conflict [2]. Deeply rooted in psychology and sociology – subjects sadly under-appreciated by the author whilst at medical school – a belated appreciation for not only interactions with patients, but human consciousness at large coalesced personally.

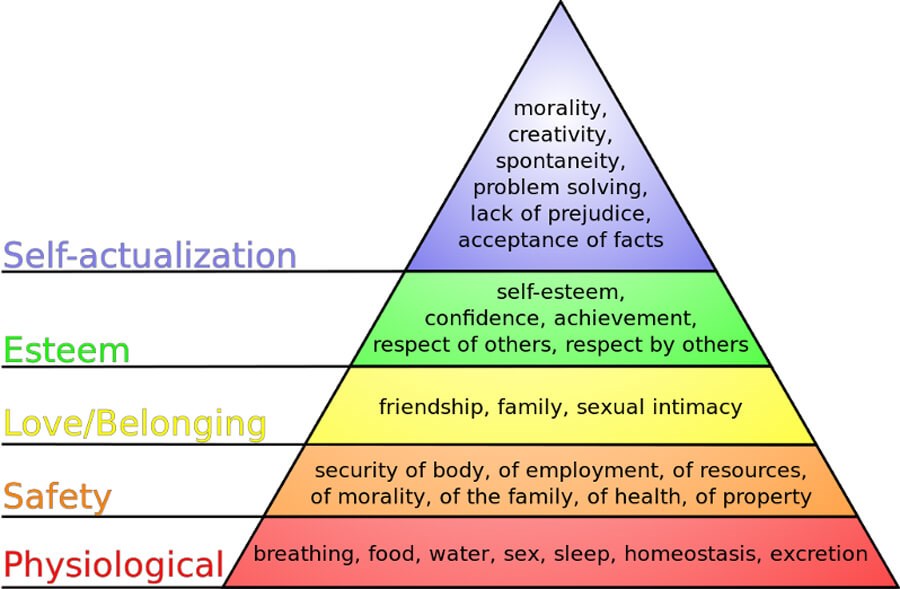

Figure 1: Schematic representation of Abraham Maslow’s pyramidal ‘hierarchy of human needs’.

With permission to reproduce granted by Finkelstein J, 27 October 2006.

Most have a passing knowledge of Abraham Maslow’s pyramidal ‘hierarchy of human needs’ (Figure 1), which by way of brief summary, holds a tenet that human motivation is driven by a hierarchy of needs [3]. Importantly, those needs are pre-potent; indicating each requires satisfying prior to progressing to the next. Thus, satisfaction of the physiological – physical discomfort of hunger, for example – would allow moving on towards safety – including the psychological security of employment, for example, although this model is now considered a little simplistic. Acceptance into a social or personal relationship satisfies belonging, thereby permitting individual freedom to work towards a degree of mastery or achievement with the ensuing recognition offered by the esteem level. Finally, self-actualisation, which aims towards the fulfilment of potential, a more esoteric stage if you will, characterised by creativity, morality and challenge. With more degrees than absolutely necessary, a clutch of post-graduate qualifications and a nascent surgical practice, I suspect it was the challenge aspect that drew me towards ocean racing.

The life of an aspirant surgeon has myriad challenges including, but not limited to: frequent geographical relocations, limited job security, professional examinations (with the odd retake!), numerous interview panels and instances of high adrenaline, possibly even panic situations. Intellectually, I surmised such features might be shared with competitive sailors and found myself giving increasing introspection into possible reasons why I should wish to risk limb, hopefully more than life, at a time of waning corporeal dexterity and energy.

With the two sharing similarities I wondered whether there were any systems for measuring changes in such environments. As fate had it, the very first week of training found me crewing alongside a personal development coach and the idea of a study promptly hatched. We sought data that might provide measurable metrics of adult development, rather complex though this ultimately proved due to the relative paucity of published literature in extreme sports. After some investigation the STAGES system was selected for being most likely workable from a data collection perspective [4], sufficiently robust to allow the possibility of tangible results and sufficiently detailed to perceive subtle shifts.

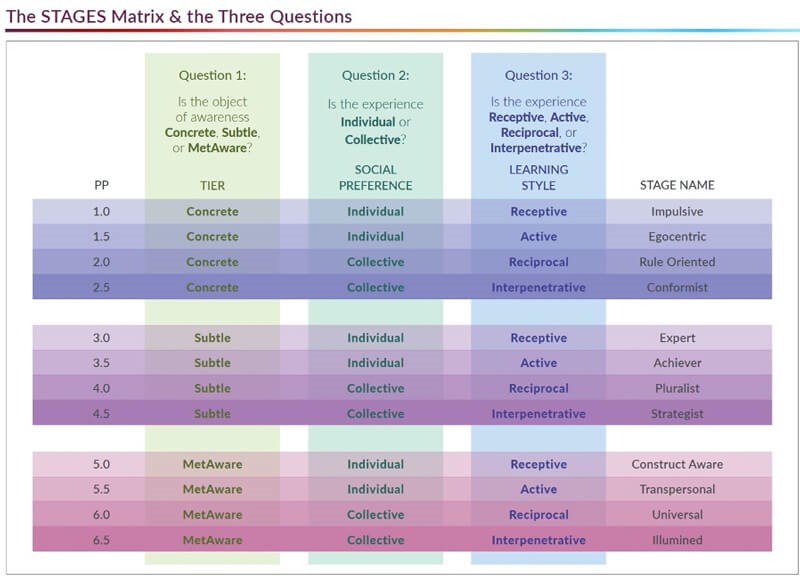

Figure 2: The Stages matrix demonstrating the benefit of parameters rather than categories for the

evaluation of development, with the three Tiers of concrete, subtle and metaware.

The STAGES system is an initially intimidating matrix (Figure 2). Part terminology, part complexity it does, however, provide a nominal scale of human development, which may therefore be measured. The matrix is a model of ego development starting at infancy and moving into increasing levels of differentiation and integration through adulthood. With 12 stages, and six different kinds of ‘perspectives’, from the first person perspective of an infant, to the third-person perspective of the scientist, to the sixth person perspective of the most advanced ego-stage on, we presently have research. Not a fixed hierarchy, the model is more like a balloon, which as our perspectives expand, transcends and includes our previous capacities. In essence, there are three tiers, more simply defined by the object of our awareness. These column 1 parameters are referred to as concrete, subtle or metaware. Column 2 defines our social orientation, individual or collective: more simply, ‘me versus we’. The final column has four subdivisions of ‘learning style’: receptive, active, reciprocal and interpenetrative.

Progressing from the rigid sense-making and thinking patterns of the concrete stage and into the subtle, we develop more abstract thinking capacities and a more subtle emotional range. Instead of simply seeing, or calling to mind, an object, there is an increased interest, and ability to, relate to how our mind actually works. This is a significant shift involving three parameters and we hypothesised the majority, if not all, the participants in an ocean race would have already achieved this developmental level, i.e., 3.0. Subsequent levels are said to be the hardest, and potentially lengthiest, to navigate.

Whilst only a single parameter shift, transition from 3.0 to 3.5 is a fundamental one in which mere curiosity and desire to understand the mind gives way to the desire to acquire understanding of how to proactively operate it. 4.0 is characterised by a more collective orientation, where relationships and collaboration become more prominent and whereby rationalisation of our own multiple ego states can lead to greater meaning and happiness. Perhaps Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life provides an apt descriptor; if not the surrealism of the film itself! 4.5 throws focus on the ability to understand, and generate systems, that allow not only our own but a greater good, from which reciprocal benefit results. Ideal qualities it would seem for harmonious function of teams in the increasingly complex surgical milieu.

Figure 3: The impressive sight of 12 identical 70-feet ocean racing yachts

ready to depart for their circumnavigations of the globe.

Statutory training saw me twice overboard in the surprisingly cold Solent, although as planned ‘rescue swimmer’ for MOB (man over board) drills, and I once experienced an inkling of genuine fear being awakened by the disorientatingly violent boat movements of a nocturnal squall during my first night sail. Race start finally arrived and we assembled in our teams on 12 identical, but rather basic (not a single shower across the fleet!), ocean-racing yachts in Liverpool’s Albert Dock (Figure 3). There is a definite hierarchy aboard and after the Skipper – the sole professional on the boat – engineers and those with any degree of medical / nursing skills were relatively sought after for obvious reasons. RTWs (round the world-ers) also exerted bragging rights over we ‘leggers’. Although a trifle incongruous to find myself ‘2nd assistant medic’ after Skipper and the RTW nurse, I was secretly delighted as I firmly intended a break after 25 virtually uninterrupted years at the sharp end.

Unfortunately, my most enjoyable and anonymous sabbatical came to an abrupt end a week into the journey to Punte del Este, Uruguay when in a sudden midnight squall in the Bay of Biscay our Skipper managed to partially avulse his left thumb. I happened to be closest, and recall two things clearly: the first being a seemingly seamless switch into ‘surgical’ mode. I also learned much from the surprising degree of ‘panic-freeze’ in some of the seasoned sailors, whilst two of the smallest and least experienced, female, crew stepped up far beyond all expectations whilst 70 feet of glass-reinforced plastic crash-gybed uncontrollably in violent wind and seas. The initially avascular digit responded slowly, but hearteningly well to metacarpophalangeal joint relocation and rudimentary treatment, but the sleepless night was filled with memories of innumerable junior nights on call as I provided a particularly attentive ‘vascular observations’ service. Being too far from land we required sea-based evacuation by the Portuguese rescue service and the surreal experience of pushing our only professional mariner off his own vessel remains on Youtube for those who may wish to view it [5]. Thereafter, I appeared to have become the de facto fleet ‘doc’, with a number of dockside ‘consultations’ at each stopover, although never was my singularly narrow skillset as apposite as when first called upon.

After a brief stopover in Porto, the Deputy Race Director took over as Skipper. I have frequently wondered whether he pushed us extra hard to avoid undue dwelling on matters, but two crew had disembarked leaving us at the bare minimum to safely crew a racing yacht across an ocean so it may equally have appeared that way. Later, I also experienced what it feels like to be outside the boat, a relatively minuscule piece of life-preserving plastic that sustains life in the unfathomably huge and ocean, during a tethered MOB situation. My providence being brought forcibly home only two legs later when a crewman of another team in a similar position was not so fortunate and perished. In any case, 33 days after leaving Liverpool we reached Uruguay and, to the chagrin of some teams already long docked, were awarded a time redress that saw us winning both Ocean Sprint and overall Leg 1 race. The pennant felt hard won by us all and remains a treasured possession.

To the study itself, numbers were always going to be limited by the practicalities of a ‘four hours on, four hours off’ watch system in which on-watch equates to safely manning the boat and off-watch the possibility of sleep. I say possibility as repairs, eating and personal hygiene are undertaken within the latter: the ‘all hands’ call mandating attendance on deck for sail wardrobe evolutions trumping all other considerations. By the time of race start we had 17 randomly selected participants who underwent a Stages assessment by a trained counsellor. After race completion a second assessment and diaries were supplied by 12. It is therefore a pilot study at best, but perhaps no less interesting for that.

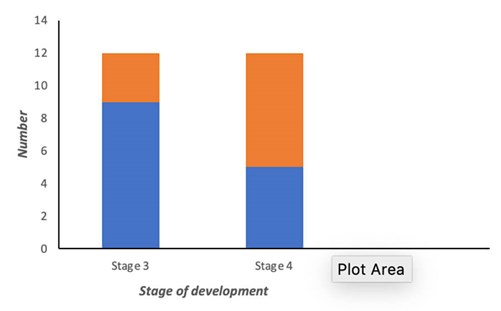

Figure 4: Pre- to post-race comparison showing a shift from the third to fourth developmental stage.

We found all participants initially had a centre of gravity from which they normally evaluated the world around them in the range Stage 3.0 to 4.5 – the full range of the subtle Tier – perhaps no surprise given the demands of the race. The apparently meagre shift to a range of 3.5 and 4.5 post-race actually shows a more marked shift when analysing the individual Stages. As Figure 4 demonstrates, four made the two-parameter jump from third to fourth person perspective. We believe this adds a little scientific weight to the intuitive belief that extraordinary challenge (or, for that matter, an extremely adverse situation as seen in one participant) catalyses human development.

It is worth acknowledging the small numbers and drop-out rate that impose their own confounding, but the speed of development – in most, Stage shifts require many years – is suggestive of correlation if not causality. As to myself, innate competitiveness, most frequently a characteristic of the 3.5 Achiever stage, whether innate or externally driven by surgical training, engendered disappointment in not having made a full Stage shift. My leadership coach’s assertion that Stage 4.0 is one of the longest, along with a considerable proportion of people who never make the shift provided a degree of mollification. I have, however, undergone intra-stage development, moved clearly beyond the goal-orientation of Stage 3.5 and entered the realm of Stage 4.0’s contextualisation and reciprocity. Moreover, I am finally appreciating the benefit of feedback (in actuality a personal stumbling block) and am, apparently, wrestling with the separate egos that form the human psyche and understanding it is normal for them to be in conflict. It is worth noting the possibility that higher than average exposure to stress-inducing situations, through surgical training, might have inured me somewhat. Evidence for emotional blunting and non-reactivity parallels between surgeons and psychopaths have been noted previously [6].

In summary, what have I learned? And would I do it again? Firstly, the reserves of human resilience are deeper than we believe. Surgery, like sailing, is very much a ‘team sport’ and anything facilitating such understanding I firmly believe translates usefully into our profession. It was volunteered after my return that I was more relaxed and a better ‘team-player’. Such excitement as witnessed aboard also tends to place tiny irritations firmly into context. Whilst exams and publications are important metrics of career progression, there are other more ‘fuzzy’ aspects that contribute to a rich and satisfying professional life. Funnily enough, they often augment professional practice. Having not ever taken more than a 10 day break previously, I was apprehensive about two full months sailing the Australasian Southern Ocean along with the ‘bucket-list’ Sydney-Hobart Race, but it proved not to be the practice-killer anticipated. In fact, quite the opposite seems to have occurred. Many, if not the majority, gravitated towards the ocean race at a challenging time of their lives and the fact we now struggle to find time for even the shortest of the great offshore races – such as the Fastnet and Antigua 600 – may be the most eloquent surrogate marker of group development in the broader concept of our lives.

Figure 5: Life at 45° when beating upwind. The sea’s surface and sole standing lookout provide spatial orientation.

Surgical skills are not just the obvious, practical ones such as witnessed during my transatlantic leg, but those we often take for granted, such as the ability to remain calm and clear-headed in times of extremis. Additionally, basics such as preparing food, and disposing of its post-digestion waste product, is really rather challenging although ultimately possible with gymnast-level contortion and practice at a not predictably stable 45° (Figure 5). Recently, it has been observed that surgeons, like sailors, must acquire a significant technical knowledge, practical skills and utilise their expertise in a very visible arena so the early findings of this study may be more applicable than first we imagined [7]. Indeed, our Skipper was the consummate technical and professional sailor, who matured from the Stage often referred to as Expert, 3.0 to the 3.5 Achiever Stage.

Finally, would I recommend it? As Sir Robin frequently reminded us, fewer have circumnavigated the planet than climbed Everest and whilst I took part in only two legs, four races and almost 11,000 nautical miles it has reminded me how useful our medical and interpersonal skills are. I now also have a rather varied, yet tight-knit group of friends I feel able to rely upon and trust implicitly in such difficult situations that might arise.

References

1. Knox-Johnston R: A World Of My Own: the first ever non-stop solo round the world voyage. Adlard Coles Nautical: London; 2004.

2. Arora S, Ashrafian H, Davis R, et al. Emotional intelligence in medicine: a systematic review through the context of the ACGME competencies. Med Educ 2010;44:749-64.

3. Maslow AH. A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychol Rev 1934;50:370-96.

O’Fallon T. StAGES: Growing up is Waking up—Interpenetrating Quadrants, States and Structures. Available from:

https://www.stagesinternational.com/

wp-content/uploads/2019/04/

StAGES_OFallon.pdf

4. https://www.youtube.com/

watch?v=ZXm6hZBh8KM

5. Pegrum J, Pearce O. A stressful job; are surgeons psychopaths? The Bulletin 2015;97(8):331-4. Available from:

https://doi.org/10.1308/

rcsbull.2015.331

6. Hotton MT, Miller R, Chan JKK. Performance anxiety among surgeons. The Bulletin 2019;101(1):20-6. Available from:

https://doi.org/

10.1308/rcsbull.2019.20

(All links last accessed October 2020)

Acknowledgement

We would like to gratefully acknowledge the input of our fellow crew in providing data at some of the most challenging times.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME