The visual impact of having a face which has scars from an accident or burns like mine or a birthmark, a cleft lip and palate, a Bell’s palsy or a skin condition is arguably not taken seriously enough by clinical teams today – and perhaps that is not surprising given the great sophistication and specialisation of medical and surgical specialists like you.

It has to be hard for you to gain sufficient understanding of the particular and unique aspects of the psychology of disfigurement – and it is still a young and not-widely-shared specialist subject in its own right.

But if one of your patients has one of those conditions, on their face in particular but it could be anywhere on their body, you’ll probably know that emotionally and socially, it is the visual impact that matters the most. Almost as much as – and some would say more than – the physical discomfort and functional problems which can be associated with those conditions.

That’s partly because, in 21st century culture, we are all so appearance-conscious, even obsessed, but also because if a person’s face has a scarred complexion or is asymmetrical or doesn’t function perfectly, he or she will get (often adverse or unwelcome) attention wherever they go. They will be the face in the crowd. The one who stands out and this can make them feel very self-conscious; low and very alone.

Here’s how one social anthropologist, Frances Cooke Macgregor, described the experience 40 years ago after studying veterans of the Vietnam and Korean Wars with disfigurements after returning to civvy street [1]. What she describes is still the case today, and perhaps even more so. People with facial disfigurements experience “a loss of civil inattention… which everyone else takes for granted.”

She went on: “In their attempts to go about their daily business, people with disfigurements are subjected to visual and verbal assaults, and a level of familiarity from strangers not otherwise dared: naked stares, startled reactions, double-takes, whispering remarks, furtive looks, curiosity, personal questions, advice, manifestations of pity or aversion, laughter, ridicule and outright avoidance.”

So what can you, the surgeon or nurse or health professional, do to help? This is the second of two articles where I ask you to get into the shoes of your patient, and see and experience the world through their eyes and their sensitivities. This is empathy.

So, just imagine for the course of this article that you are the patient. How could ‘you’ be helped to manage that reality, a viewpoint which, I believe, enhances the understanding of health professionals.

To revisit what is known about that reality, you (again as the patient) are likely to experience, psychologically and socially, three key problems:

- Intra-personal: inside, you may feel a mixture of grief at the loss of your identity, anger, aloneness and depression, denting your self-esteem.

- Inter-personal: you will probably find that everyday social encounters become very challenging: being stared at intrusively, avoided, asked curious questions, patronised, called names, and worse – being ridiculed or rejected.

- Medical uncertainty: understanding what’s happened to you and making decisions about potential treatments can be problematic.

The good news, however, is that many people do adjust successfully to these challenges – some do so entirely on their own and quite quickly though most acknowledge the support and benefit from professional help. However, there are others, too many, who do not adjust quickly and, not knowing that there is professional help available, suffer in silence.

Research [2] and Changing Faces’ experience over more than 20 years has established that adjustment is enhanced if people like you have access to the FACES package:

- FINDING OUT: You find out what medicine, surgery and other treatments, such as skin camouflage, can offer and decide what’s right for you.

- ATTITUDE: You and your family develop positive attitudes and beliefs about the future, quashing the prevailing pessimism about your prospects if you look unusual.

- COPING: You come to terms with your feelings and that may require some outside help.

- EXCHANGING: You discover you are not alone with your condition and you may benefit from meeting others in the same boat.

- SOCIAL SKILLS: You learn the social skills to manage other people’s various reactions to your unusual appearance.

The first article [3] focused on the importance of F for ‘finding out’ – and being helped to find out – what your condition is, how it can be best treated, what the risks and benefits are of such interventions, etc, all of which will enable you to be more in control of the condition itself. It also explored the significant value of cosmetic camouflage creams as one of the range of physical therapies available.

This article looks at the other four elements of the FACES package which Changing Faces has evolved from our 22 years of helping thousands of people with disfigurements like you and from the limited amount of research that has so far been done on the psycho-social issues and interventions of ‘looking unusual’.

We train ‘Changing Faces Practitioners’ (CFPs) to deliver the FACES package. They are professionals already trained in the caring professions to offer sensitive, confidential and empowering support which enables many people to acquire ‘disfigurement life skills’.

A practitioner could enable you to feel more understood and more positive about your appearance and your future. A CFP can support you to enhance your self-confidence and self-belief by carefully assessing and then encouraging you to choose, with suitable advice, from the FACES package of help, which complements the other interventions such as plastic surgery which you may be undergoing concurrently:

A – Attitude-building

Today’s culture is full of images and stories about the downsides of having a disfigurement to your face or body and it is therefore understandable that you may well imagine this to be a disaster. Assumptions and myths about what life is like for someone living with a disfigurement are deeply rooted in our culture and can distort the reality of disfigurement. People can react with fear when seeing someone with a disfigurement, perhaps a consequence of the myth of evil being linked with scars and marks that is so propagated across the media [4].

These negative connotations and the stigma often associated with disfigurement makes managing other people’s reactions and unwanted attention (staring, double takes and comments) upsetting and intrusive, and can make daily activity difficult to cope with.

Part of our work at Changing Faces is to ‘change minds’ by campaigning for what we call ‘face equality’ (like race equality). We challenge misrepresentations and instances of facial prejudice prevalent in today’s culture with the aim to transform public attitudes towards people with an unusual appearance. But that will take years to deliver, we know.

In the meantime, our practitioners can support you to develop a realistic, positive and strong outlook to your future, helping you to review any unhelpful thoughts (‘self-talk’) and negative beliefs about your disfigurement, and / or to meet or hear about role models in order to be encouraged and motivated to see a better future and be strong in the face of negativity.

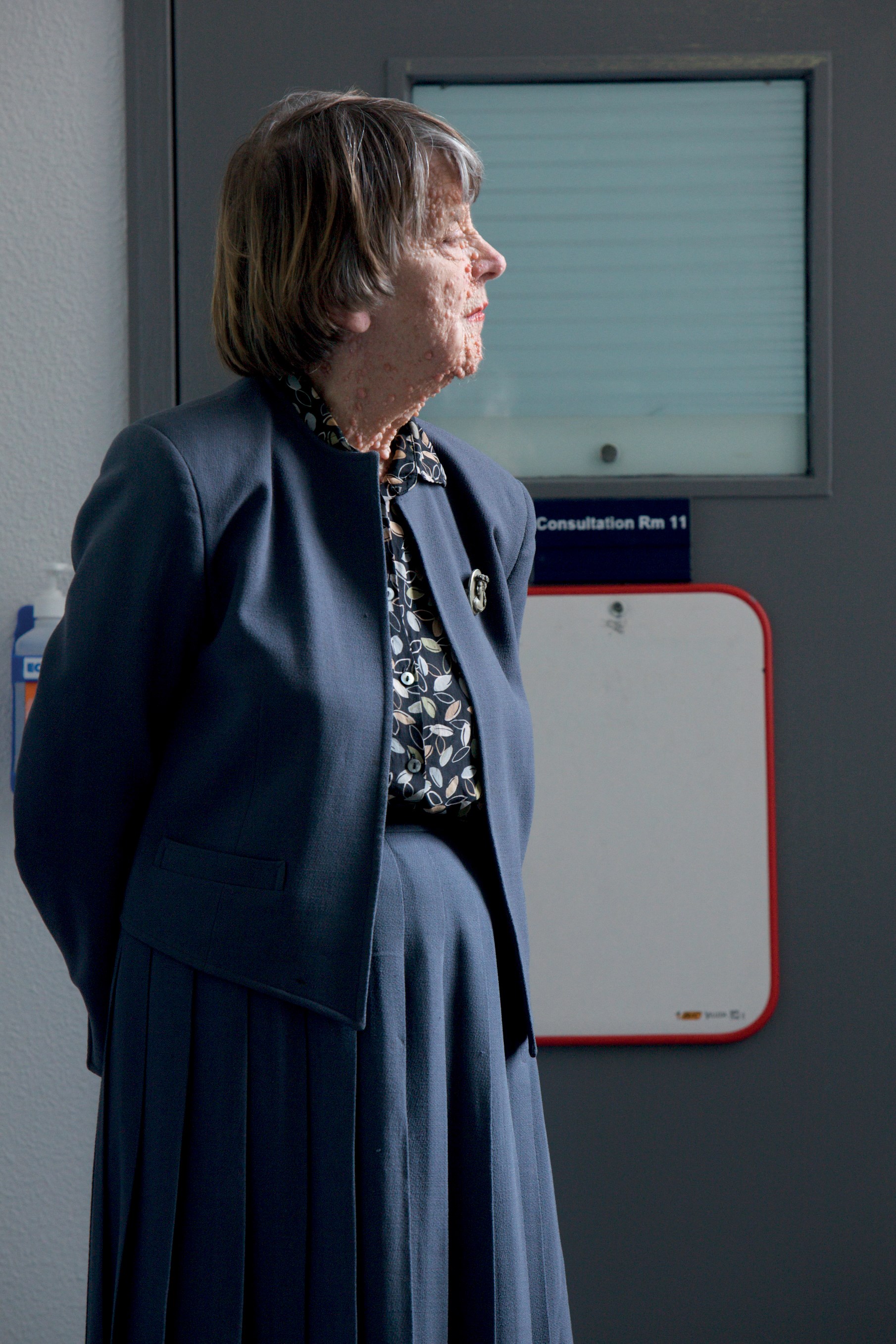

© Piers Allardyce for Changing Faces

C – Coping with feelings

Having an accident or operation that affects your face or body, or acquiring a facial palsy or skin condition, can be very distressing indeed for the individual affected and their whole family. There are many things that can contribute to how you cope and adjust positively to your disfigurement. Social support from your friends and family can be vital. And you may find joining a local support group helpful too.

But you may want to confide how you feel about what you are going through. Maybe to your family or close friends although many people find this difficult.

Our CFPs can provide a safe space for you to explore your feelings and help you to develop coping strategies to reduce distress and support you to cope with your feelings of grief, anger, sadness and lost identity. They can help you develop resilience which is not always an innate trait but can be learnt over time [5]. With the right support, you can come to terms with your feelings and develop resilience that will help you adapt to difficult situations and have a positive outlook about your future.

E – Exchanging

Many people have never met anyone who has a disfigurement and so it is not surprising that you may feel very alone, very different and even outside the norms of society. Meeting and sharing experiences, exchanging information as well as knowing you are not facing disfigurement alone, and finding out that others share similar challenges can help you normalise your feelings.

People often contact Changing Faces in the hope of meeting others who are going through a similar experience, to exchange notes, share feelings and gain mutual support. Our CFPs run workshops to bring people together and can signpost you to appropriate information and support groups [6].

S – Social skills

First time meetings are challenging for us all. Meeting someone with a facial disfigurement for the first time can be daunting for anyone. And if you have a disfigurement, you can find everyday social encounters such as walking down the street very difficult to manage. People often say they find it difficult – and are afraid – to leave the house, to make new friends or socialise with old, and to find a job. And school playgrounds, social media and public transport can be a nightmare.

To live confidently with a disfigurement, it is vital that you develop robust and effective skills to manage other people’s reactions using a wide and flexible range of skills. Our practitioners can help you to learn new strategies for managing everyday encounters and other people’s reactions to your disfigurement, such as staring, questions and rudeness, and to strengthen your skills for asserting yourself and becoming more socially confident.

Social anxiety, other mental health concerns and behavioural issues can arise in response to disfigurement and to the attendant stigma and discrimination which adults, young people, children and their families experience. The impact of these difficulties on social interactions, school engagement and employment (all of which are evidenced to be critical factors in quality of life and well-being) can be extremely detrimental.

So you may find access to the FACES package useful – and there are several ways of accessing it: by making personal contact, by looking at our self-help guidance online [7] or by asking your surgical team if the sort of help that CFPs offer is available locally. And if it isn’t, perhaps the team could find out from Changing Faces how such a post could be created. Key elements of the FACES package have been tested in our own setting, within the NHS and in other countries and have been found to be effective for children, young people and adults. However, there is still a lack of high-quality trials.

The good news is that new psychological support services reflecting the FACES principles are emerging in the NHS, with (and sometimes without) our support. As well as the CFPs employed by the charity in London and Sheffield, there are now three other CFPs working in NHS settings, the first from September 2012 in the paediatric plastic surgery team at the Royal Hospital for Sick Children in Edinburgh, and the others in the Dermatology team at Great Ormond Street Hospital and the Yorkhill Hospital for Children in Glasgow. An adult-focused CFP works in the maxillo-facial surgery team at Salisbury Hospital. The first primary care CFP service opened in North Leeds in February [8]. In NHS terms, CFPs are offering primarily a Tier 2 service. We aim that they become embedded in many more NHS clinical teams in future years.

A recent report on the work of the CFP at the Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh found that last year, she supported 173 children, teenagers and parents. It also reported that every single child and parent reached said that they felt more able to manage the issues that were previously concerning them. “I feel like a weight has been lifted,” said one parent. Our 2013-14 clinical audit demonstrated that 91% of patients surveyed believed the service was helpful or very helpful for coping with a disfigurement.

A key aim of our practitioners’ role, in addition to providing direct support to you as the patient, is raising awareness and educating health professionals, schools and others about Changing Faces and the psycho-social impact of disfiguring conditions.

© Piers Allardyce for Changing Faces

The CFP employed by the Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh since 2012, has demonstrated that support from our practitioners can reduce clinical contact time and save the NHS money. A consultant cleft and plastic surgeon within the hospital commented that: “My clinics are less likely to overrun since patients are well informed (by the CFP) and I do not need to do the signposting towards Changing Faces (community service) that I used to do. Additionally, if a child is distressed about bullying or name calling they now receive all the support they need from (the CFP) (including ongoing support and home visits). Previously I would have done all I could to counsel the child and family and offer support, worried that in the absence of this, the family had no other access to the support they needed. This however, always used to lead to my clinics running very late, inconveniencing other patients and their families [9].”

So, to conclude, there is a lot that you – as a person or patient with a disfiguring condition – can be helped to do by your healthcare team. Research suggests that the right psycho-social support at the right time not only reduces the distress experienced by patients like you, it also significantly reduces the risk of developing psychological problems later in life.

The message to clinicians is that ensuring that patients have access to the FACES package is likely to significantly improve their self-esteem and confidence and their quality of life, as well as reducing the workload for healthcare professionals.

References

1. Macgregor FC. Facial disfigurement problems and management of social interaction, implications for mental health. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery 1990;14(4):

249-57.

2. Clarke A, Thompson AR, Jenkinson E. CBT for Appearance Anxiety: Psychosocial Interventions for Anxiety due to Visible Difference. Wiley Blackwell; 2014

3. Partridge J. Looking unusual: what it’s like and how skin camouflage can help. PMFA News 2014;2(1):6-8.

4. Changing Faces’ Face Equality campaign:

https://www.changingfaces.org.uk/

Face-Equality

Last accessed March 2015.

5. The Road to Resilience. American Psychological Association (APA); 2008.

http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/

road-resilience.aspx

Last accessed March 2015.

6. The Changing Faces’ adult support service:

https://www.changingfaces.org.uk/

Adults and workshops:

https://www.changingfaces.org.uk/

Adults/Workshops-for-adults

Last accessed March 2015.

7. Changing Faces e-resource on social skills for young people:

http://learn.happyelearning.co.uk/

clients/changingfaces/home.html;

self-help guides for adults:

https://www.changingfaces.org.uk/

Adults/Self-help-guides;

self-help guides for parents:

https://www.changingfaces.org.uk/

Children-and-Families/Self-help-information-for-parents;

self-help guides for children and young people:

https://www.changingfaces.org.uk/

Children-and-Families/Self-help-information-for-children

Last accessed march 2015.

8. Gulland A. Can GPs do more to help patients with facial disfigurement? BMJ 2015;350:h1160.

9. Report on the evaluation of the CFP employed by the Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh: available on request.

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.

Editor’s comment

I have known James for many years and recognise him as a very special person. He exudes a natural charisma and charm and one wonders where he would be now if the Landrover had been designed with the petrol tank at the rear. He is a tremendous example that there can be triumph over adversity. There are many good quotes that are applicable to James and the Changing Faces team and this is just a selection. http://www.goodreads.com/quotes/tag/triumph

James, I salute you and deeply appreciate your inspired and sensitive contribution to rebuilding the lives of so many people. Thank you, AB.

Exploring the Psychological and Social Challenges of Disfigurement

Explore how you can support your patients to face the psychological and social challenges following disfigurement at a Changing Faces Study Day and earn a minimum of six CPD points. For more information visit the website https://www.changingfaces.org.uk/Health-Care-Professionals/Training/Study-days or contact Swati Pandit at Changing Faces on swati.pandit@changingfaces.org.uk or 07535026628.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME