The demand for reconstruction of mutilated female genitalia is increasing in Europe due to the empowerment of immigrant and naturalised women from Africa. Their wish for reconstruction is more than a matter of surgery, as these women still have to deal with prejudice from peers, family and, last but not least, our society [1,2,3,4]. Furthermore, there is a real chance of reliving the trauma of the initial mutilation [1,3,5]. Such patients require a multidisciplinary team approach to address their needs in a holistic manner.

Definition and background

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons” [1]. FGM is practised as a cultural ritual in Africa, and to a lesser extent in Asia, the Middle East and within immigrant communities in Europe. It is typically carried out, without anaesthesia, by a traditional circumciser using a knife or razor. The age of the girls varies from toddler to puberty [1].

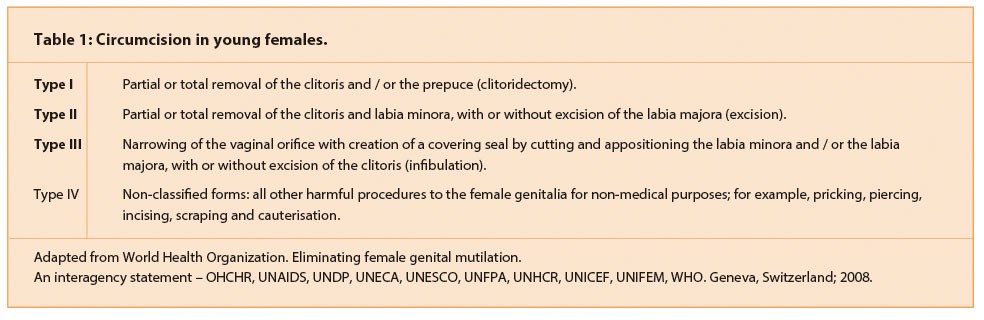

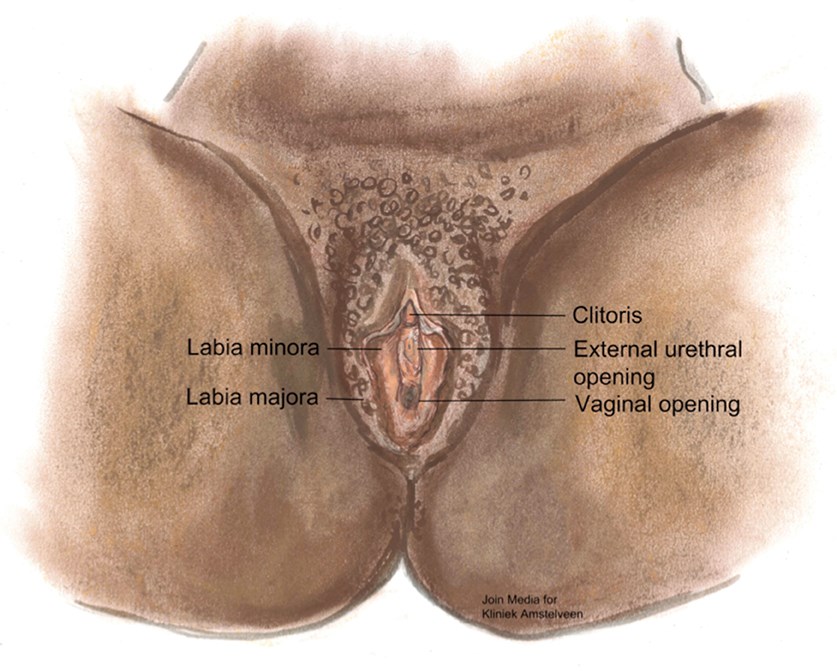

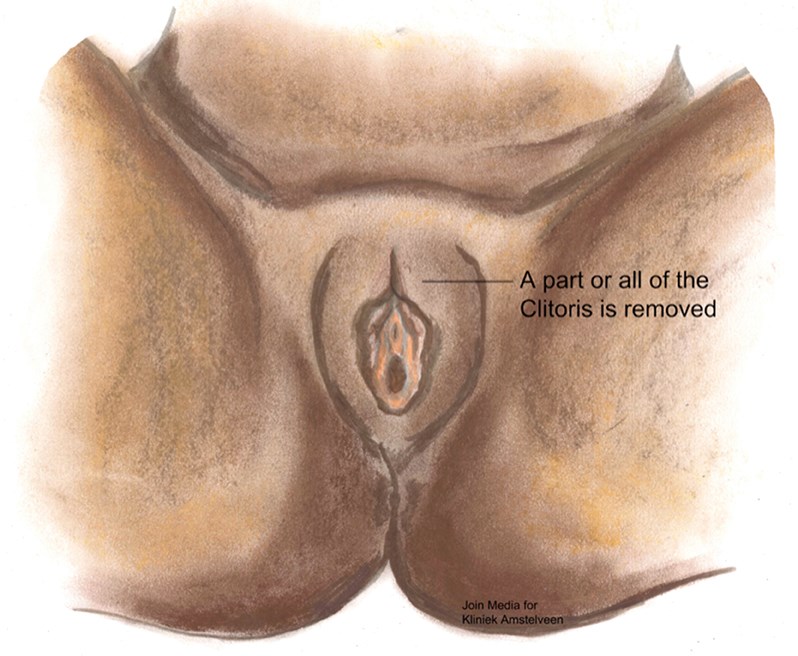

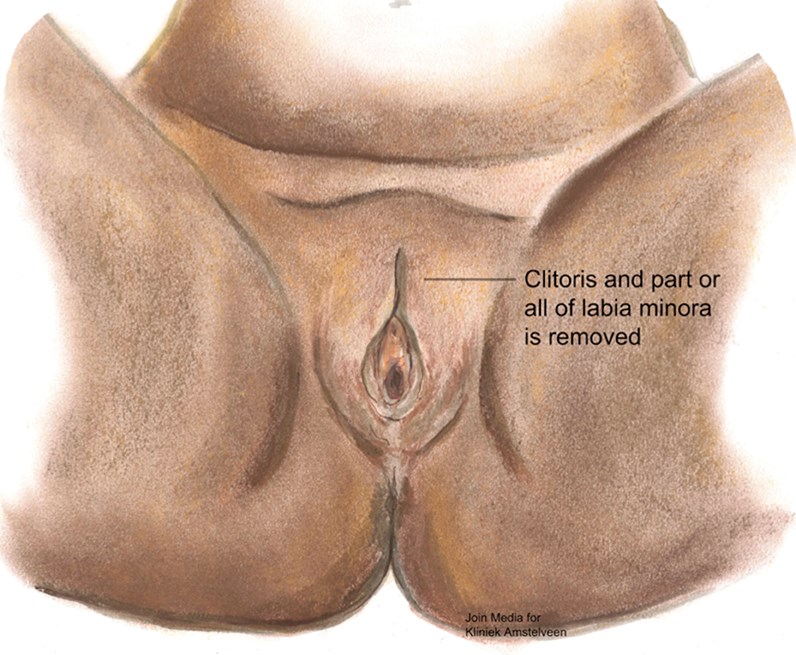

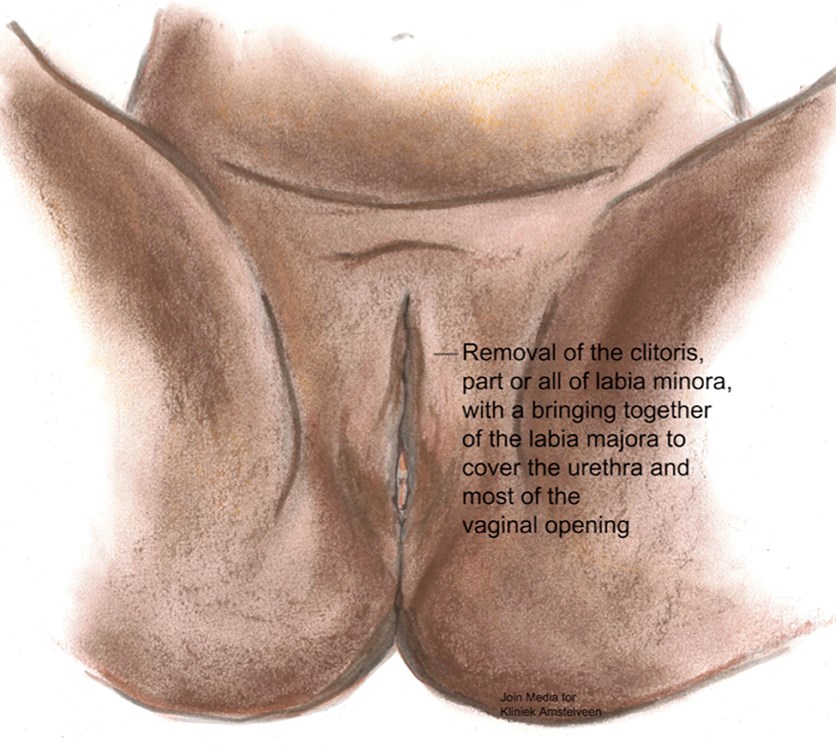

The practice involves one or more procedures (Table 1), which vary according to geographical region and local cultural practices (http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs241/en/). All procedures include removal of all or part of the clitoris and clitoral hood (Figure 1 and 2); Type II is combined with the removal of inner labia (Figure 3); and in its most severe form (infibulation) all or part of the inner and outer labia are removed and the resulting wound is sutured (Figure 4). In this last procedure, Type III FGM, a small hole is left for the passage of urine and menstrual blood, and the wound is opened up for intercourse and childbirth. The detrimental effects on health depend on the procedure [1,4].

Figure 1: Normal female genital anatomy.

Figure 2: Type I female genital mutilation.

Figure 3: Type II female genital mutilation.

Figure 4: Type III female genital mutilation.

About 125 million girls in Africa and the Middle East have undergone FGM [1]. The practice has a tribal origin, probably based upon gender inequality. It is broadly supported by women and men in countries that practise it. The women are the gatekeepers and initiators of this rite and they generally see it as a source of honour and authority, and a part of raising their daughters.

Complications

By definition, FGM does not serve a medical purpose. It has immediate and late complications, which depend on several factors: the type of FGM; the conditions in which the procedure took place and whether the practitioner had medical training or not; whether unsterilised or surgical instruments were used; whether surgical thread was used instead of thorns; the availability of antibiotics; how small a hole was left for the passage of urine and menstrual blood [1,3]. Immediate complications include bleeding, infection, urinary retention and infection, septicaemia, tetanus and of course transmission of hepatitis and HIV. It is not known how many girls die from the initial procedure [1].

Late complications vary from the formation of scars and keloids and strictures leading to obstruction. Damage of the urethra and bladder may lead to chronic infections and incontinence and in severe cases the developing of vesicovaginal or rectovaginal fistulae. Genital tract damage includes vaginal and pelvic infections, painful periods, pain during sexual intercourse and infertility, among others [1,4]. Other complications include epidermoid cysts that may become infected and neuroma formation [1,4]. When this type of late complication occurs it can complicate pregnancy and thus has a higher risk for obstetrical problems.

Psychological complications such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder are more often seen in this group [1,2]. Feelings of shame and physical incompleteness may develop when the women learn that their condition is not the norm. Painful sexual intercourse and reduced sexual feelings are common but FGM does not necessarily destroy sexual desire in women.

“The wish for reconstruction is growing throughout Europe and has to be addressed by the medical community.”

Awareness and policy in western countries

New immigrants from Africa brought the tradition of FGM to Europe and the practice spread throughout Europe and North America. Families who have emigrated from practising countries initially send their daughters home to undergo FGM, and there have been reports of parents arranging for traditional circumcisers to fly to Europe to perform the procedure. This was a new phenomenon which required action from the European community.

Since the 1970s there has been a global effort to achieve a humanitarian consensus to stop this practice. In Europe, Waris Dirie, a former top model from Somalia, has contributed to raising the awareness of the reality of FGM through the Desert Flower Foundation which remains an active voice [6] (www.desertflowerfoundation.org). The European and African effort, with both big and small projects, culminated in a political voice and a resolution in 2012 by the United Nations General Assembly to take steps to end FGM. Today a total ban on all forms of circumcision in young girls is the standard policy in Europe.

Genital reconstruction the next step

Due to the empowerment of the naturalised women from Africa, the wish for reconstruction is growing throughout Europe and has to be addressed by the medical community. The French Surgeon, Pierre Foldès, was the first to reconstruct the clitoris after FGM and achieved good results [5,7,8]. His procedure consists of the removal of scar tissue, and lowering of the clitoris stump by cutting ligaments that support it while preserving nerves and blood vessels. In his latest study, 2938 women received clitoral reconstructive surgery, during which 5% experienced minor complications following surgery. Eight hundred and sixty-six women responded to a follow-up survey conducted a year later, 821 reported that their pain had improved, 815 reported that clitoral pleasure had improved, 2% had less clitoral pleasure than before the procedure [5].

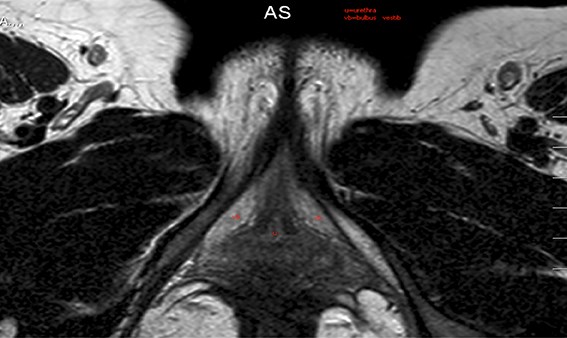

Figure 5: MRI of the clitoral crurae.

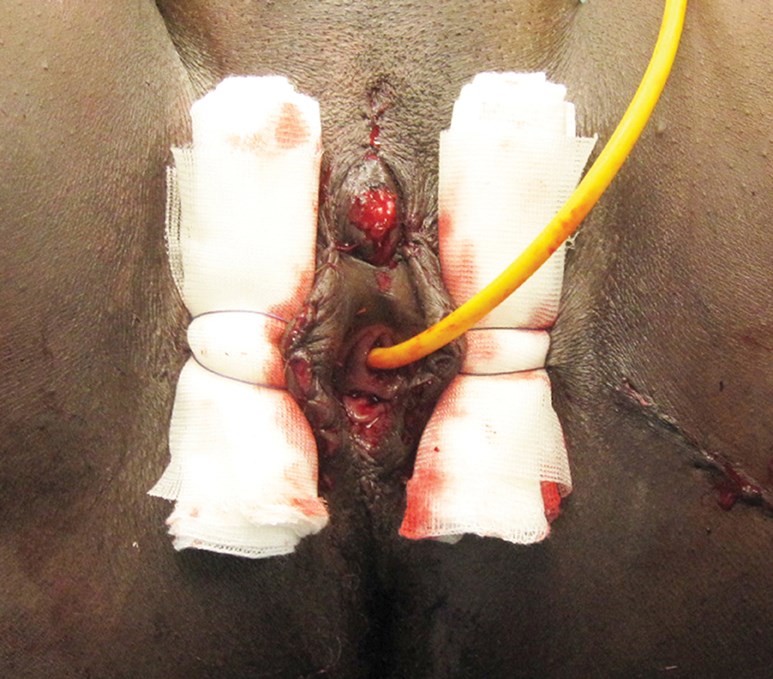

In 2010 the first patient came to our outpatient clinic with the request for genital reconstruction after FGM. Since that time there has been a steady stream of patients coming to our clinic. Many of these women have a common history of fleeing warzones in Africa and also being victims of war violence. Furthermore many of these women could still recall the trauma of the initial rite. By taking the decision to undergo genital reconstruction these women are facing the possibility of being alienated from their own family and culture. While treating these patients it is essential to keep this social / cultural context in focus. We try to match the patient with a female case manager whom the patient can approach for support and information and who can be an advisor throughout the course of treatment. In the beginning we take scans to visualise the clitoral stump (Figure 5). At present we are operating on at least two patients a month. The operation can be done as a day surgery procedure under general anaesthesia. If the patient also wants a labia minora reconstruction then they need to be admitted for at least 24 hours. See Figure 6 for surgical photographs of the reconstruction.

Figure 6a (above left): Preoperative.

Figure 6b (above middle): Perioperative.

Figure 6c (above right): Direct postoperative.

Reimbursement

This new demand for basic healthcare causes the health insurance companies some embarrassment. Should they pay or not pay for this treatment [9]? In principle this is a task for national policymakers and the national parliaments. Widespread political support is needed. As long as there are no national guidelines the health insurance companies may do as they please and the patients are at the mercy of arbitrary decisions of individual agents.

Conclusion

FGM is recognised internationally as a violation of human rights. Today a total ban on all forms of circumcision in young females is the standard policy in Europe. As we accept this as a mutilation then we have to take the next step to try to reconstruct the patient, if and when there is a demand for a reconstruction. Therefore we believe, from both medical and ethical perspectives, that genital reconstruction after FGM should be provided as a service to be undertaken by specifically trained surgeons and should be reimbursed from the basic healthcare insurance policy. Finally, one of the greatest benefits of genital reconstruction is that these women will, in turn, protect their daughters from the cruel and inhuman abuse that constitutes female genital mutilation.

References

1. World Health Organization. Eliminating female genital mutilation. An interagency statement – OHCHR, UNAIDS, UNDP, UNECA, UNESCO, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNIFEM, WHO. Geneva, Switzerland; 2008. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/

publications/fgm/9789241596442/en/

Last accessed March 2014.

2. Vloeberghs E, Knipscheer J, van der Kwaak A, et al. Versluierde pijn, Onderzoek naar psycho-sociale gevolgen van meisjesbesnijdenis. 2010-120 blz.-978-90-75955-72-9-ISDN.

3. EURAPS 2013. Reconstruction after FGM Kliniek Amstelveen.

http://www.youtube.com/

watch?v=ck9d-PErYWM

Last accessed March 2014.

4. Vos C, van Roosmalen J. Een klein onderwerp: vrouwelijke genitale verminking Ned Tschr Obst Gyn 2013;126:447-50.

5. Foldes P, Cuzin B, Andro A. Reconstructive surgery after female genital mutilation: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 2012;380(9837):134-41.

6. Dirie W. Desert Flower: The Extraordinary Life of a Desert Nomad 1st edition. William Morrow Pub; 1998.

7. Foldes P. Chirurgie plastique reconstructrice du clitoris apres mutilation sexuelle. Prog Urol 2004;14:47-50.

8. Foldes P. Reconstructive surgery of the clitoris after ritual excision. J Sex Med 2006;3(6):1091-4.

9. VAGZ. Werkwijzer beoordeling behandelingen van plastisch-chirurgische aard. 2012

https://www.iak.nl/Zorg/~/media/

Files/Zorg/2013/Overig/Werkwijzerbeoordeling

behandelingenvan%20plastisch

-chirurgischeaard01-2013.pdf

Last accessed March 2014.

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.

TAKE HOME MESSAGE

-

FGM is recognised internationally as a violation of human rights.

-

By definition, FGM does not serve a medical purpose. It has immediate and late complications.

-

The need for genital reconstruction is growing in Europe due to the empowerment of the migrated and naturalised women from Africa in our culture.

-

The next step is to reconstruct the patient, if and when there is a demand for a reconstruction.

-

Furthermore there is no better warranty than a reconstructed mother to protect her daughters against FGM.