The demand for female cosmetic genital surgery (FCGS) has increased over the last decade [1]. This rise is difficult to quantify, as the majority of these procedures are performed in the private sector. However, this trend is also obvious within national health systems (NHS, UK), where the number of operations coded as ‘excision of excess labial tissue’ increased from 568 in 2002 to 1,064 in 2008 [2].

A number of reasons could explain the increasing demand for FCGS. Younger women favour less pubic hair, which results in easier visualisation of the external genitalia [3]. Increased access to female body images on the Internet, TV and in magazines has raised awareness of genital appearance and skewed the perception of normality towards adolescent features, with flat vulvas without protrusion behind the labia majora [4]. TV shows and articles in lifestyle magazines on FCGS might also influence the desire for a ‘face lift of the vulva and vagina’, together with the rising number of cosmetic procedures in general.

Advertisement and aggressive marketing of FCGS could also inflate the demand for surgery. A recent Google search for ‘cosmetic genital surgery’ highlighted more than 2,000,000 items, whereas a Pubmed search found only 234 items, demonstrating the huge increase in interest regarding this type of surgery by the general public with the medical profession being far less well informed.

The quality and quantity of clinical information on FCGS provider sites is poor, with erroneous information in some instances [5]. This field has been described “like the old Wild, Wild West: wide open and unregulated” [6]. The majority of FCGS procedures are poorly defined and there is no standardised terminology. The use of non-medical terms, such as ‘designer vagina’, ‘vaginal rejuvenation’, ‘laser vaginal rejuvenation®’ or ‘G shot®’, makes the scientific assessment of these operations very difficult.

The terminology needs to be standardised in an effort to avoid ambiguity and inconsistency [7]. Additionally, conflicts of interest prevent studying trademarked or proprietary treatments [8]. There is a well-recognised lack of robust evidence on the safety and benefits of these procedures [9]. In view of this, colleges and associations of obstetrics and gynaecology have issued warnings about the performance of such operations [10].

Ethical issues

The rising number of these operations has also highlighted the controversy about the relationship between FCGS and female genital mutilation (FGM). FGM comprises all procedures that involve “partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons” [11] and is a criminal offence in most of the western world countries. In the UK, the Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003 excludes surgical operations which are necessary for woman’s physical or mental health [12]. However, as there is limited evidence regarding the benefit of FCGS for physical and mental health, some campaigners suggest that medical practitioners performing such procedures should be prosecuted [13].

Another controversial issue is the funding of these procedures. The majority of the operations performed for purely aesthetic reasons are carried out in the private sector and are self-funded. But a share of the demand for FCGS is being absorbed by publicly funded health care services [14]. Health care providers should discourage the use of public funds for the performance of purely cosmetic procedures. Nevertheless, if FCGS procedures have physical or mental health benefits or are being performed for functional reasons, it might be justifiable to attract public funding. A clear and strict selection process of appropriate candidates for FCGS is required to allow allocation of government funding.

Normal anatomy and patient perception

A robust selection process would be impossible without understanding of the normal anatomy of the female genitalia. A small cross-sectional study reporting on the normal dimensions and exact positioning of the vagina, urethra, clitoris and labia, showed a wide natural variation of these features [15]. The mean labia minora width was 21.8 mm, but with a broad range of 7-50mm, and their length was 60.6 mm with a range between 20 and 100mm. These results have challenged a previous definition of labia minora hypertrophy, which used a width of 40mm as cut-off [16].

Surprisingly, labial measurements of a cohort of 33 women requesting labial reduction surgery were all within the published normal range [17]. A comparison of labial measurements between women seeking labiaplasty in an NHS gynaecology clinic and those in a private cosmetic clinic has shown that NHS patients appeared to have significantly greater labia minora width than the private patients (mean 40.27 vs. 28.09 mm, p<0.001) [18]. Increased access to genital pictures may narrow the social definition of normal and increase the desire to emulate what is perceived as being attractive. Considering the enormous natural variation of the topographical features of the female genitalia and the overlap between women seeking FCGS or not, it is difficult to use anatomic measurements as objective criteria for surgery.

Types of FCGS

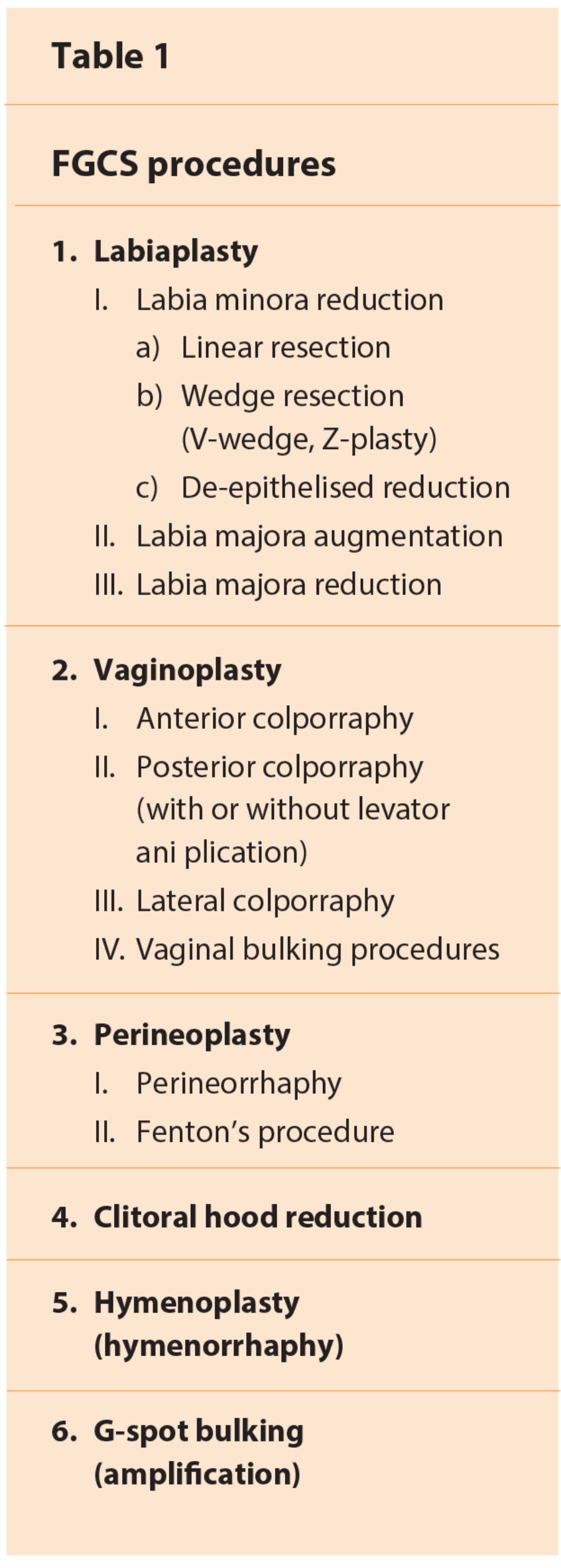

There are a number of procedures included under the umbrella term FCGS (Table 1). It is of paramount importance to use descriptive and standardised terms such as those employed in the field of urogynaecology / female urology, rather than trademarked or commercial names. The procedures could be further subdivided based on the operating instruments such as laser, radiofrequency, electrocautery or ‘cold knife’. For laser-assisted procedures, different types of laser (CO2, Er:YAG, Nd:YAG) have been used for excision or ablation [19]. For bulking procedures, the most commonly used materials are hyaluronic acid and autologous fat.

Indications

Women seek FCGS for aesthetic, functional, sexual and cultural reasons. A number of physical complaints are described by these women, such as pain, discomfort or irritation associated with clothing, exercise, sexual intercourse, as well as sensation of vaginal relaxation and lack of coital friction. In a retrospective study of 131 patients undergoing labiaplasty, 32% were seeking surgery strictly for functional impairment, 37% for cosmetic reasons only and 31% for both functional and cosmetic reasons [20]. In a different multicentre cohort of 258 women undergoing FCGS, 64% reported discomfort preoperatively, 48% cosmetic reasons, 33% wanted surgery for self-esteem and 30% for sexual enhancement [21]. In the same study, the majority of women undergoing vaginoplasty and / or perineoplasty expected increase in their (58%) or their partner’s (54%) sexual pleasure. Women referred to an NHS gynaecology clinic by their general practitioner are more likely to report functional reasons, compared to self-referred women to a private cosmetic clinic [18].

The request for hymenoplasty is rather different and raises further ethical issues. It is usually made by a different group of patients. They often come from specific ethnic / religious groups, especially African and Middle Eastern countries, where bleeding during post-nuptial intercourse and vaginal tightness are considered proofs of virginity [22].

Outcomes

Despite the increasing interest in FCGS, only limited outcome data have been published in the literature. The majority of the studies are retrospective, single-centre case series with short-term follow-up (Level of evidence III – IV), which report subjective, non-validated outcome measures. Every study shows a success / satisfaction rate of more than 80% [23]. In a large multicentre study, 97% of patients undergoing labiaplasty and 83% of patients undergoing vaginoplasty / perineoplasty felt that they achieved their goals postoperatively. Improvement of their sexual function was reported by 64% and 86% of women respectively [21].

The incidence of reported complications varies in the literature (3.8%-23.8%). A wide range of postoperative complications have been reported such as infection, haematoma, dyspareunia, localised pain, altered sensation, poor wound healing, scarring, wound separation and even bowel and bladder injury with fistula formation. The majority of these complications are considered as minor by the authors of the relevant papers, which do not apparently interfere with overall satisfaction [23].

Preoperative considerations

Women should be adequately counselled and provide informed consent about FCGS procedures. They should be educated about the wide variety of normal female genital appearance and be reassured about their genital anatomy. Special attention should be paid to younger girls, as the development of external genitalia continues throughout adolescence. Ideally, any surgical intervention should be delayed until development is fully complete. Women seeking FCGS should be made aware of the lack of robust scientific evidence about the safety and efficacy of these operations. Preoperative counselling regarding functional, sexual and cosmetic benefits should be balanced against potential risks to help patients develop realistic expectations. Physicians should declare any conflicts of interest for treatments, where commercial rights are involved.

The relevance of psychological issues in cosmetic surgery has been well established in the literature and the increased prevalence of underlying psychopathology in patients requesting surgery has been recognised [24]. Women seeking labiaplasty do not differ from controls on measures of depression or anxiety, but they have a worse body image quality of life (p=0.041) and they are more likely to suffer from body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) (18% vs. 0%, p<0.001)[18].

Consequently, screening for psychopathology during the preoperative interview is essential. Based on this, the surgeon could refer patients to a psychologist or psychiatrist and withhold FCGS from women with significant mental impairment. We recommend the routine use of the Genital Appearance Satisfaction (GAS) scale, an 11-item tool and the Cosmetic Procedure Screening Scale modified for labia (COPS-L), a nine-item instrument, which are both validated in women seeking labiaplasty [25].

Another challenging group are patients with sexual dysfunction. Although the majority of women undergoing FCGS, mainly vaginoplasty and perineoplasty, expect improvement of their sexual function, caution in the preoperative counselling is required. There is a lack of good-quality data regarding sexual outcome after FCGS and therefore patients should be aware that functional and cosmetic benefits are the basic indications for these operations.

Validated instruments of sexual function / dysfunction such as the Golombock-Rust Inventory of Sexual Satisfaction (GRISS) [26] or structured screening questions should be used preoperatively. Women with significant sexual dysfunction should be referred to a qualified psychosexual therapist before any planned surgical intervention.

Service provision

In the current unregulated environment of FCGS, gynaecologists, urogynaecologists, plastic surgeons and urologists perform these operations. Despite the absence of structured training programmes, the majority of the plastic surgeons in the USA (51%) offer FCGS with a mean workload of 3.68 procedures per year [27]. These procedures are not considered gynaecologic or urologic and generally are not taught during residencies, as there are no training guidelines. In view of the increasing demand of these operations the relevant surgical professional bodies should provide some guidance on training and practice requirements. As with other surgical procedures, service accreditation should be based on education, training, experience and demonstrated competence.

FCGS should ideally be provided by a multidisciplinary team (MDT) of health care professionals, similar to the model recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for the management of urinary incontinence in women [28]. The MDT should include at least two operating surgeons, a psychologist / psychiatrist, a psychosexual therapist and a physiotherapist. Having representation from professionals with different experience would allow a wider choice for patients and better patient selection.

An MDT review before all surgical procedures could save future problems arising from poor decision-making and potentially increase patient satisfaction. Furthermore, the MDT would also be able to make special clinical governance arrangements, audit interventions and continuously monitor and review outcomes. A national or international registry for FCGS procedures or an online database tool, similar to the one offered by the British Society of Urogynaecology for prolapse and urinary incontinence surgery, could create a regulatory mechanism in the field.

Conclusions

FCGS is a rapidly expanding and poorly regulated field of cosmetic surgery. Despite the controversies, the relevant surgical professional bodies should attempt to regulate training and performance of these procedures. The terminology should be standardised and descriptive in order to improve consistency and allow systematic review of the literature. Emotive terms such as ‘designer vagina’, ‘laser vaginal rejuvenation®’ or ‘G shot®’ should be abandoned in an effort to avoid confusion and develop realistic patient expectations.

Well-designed prospective randomised controlled trials or comparative studies with long-term follow-up, which use validated tools and patient reported outcomes, are needed. Patients should be carefully counselled and selected preoperatively ideally by a multidisciplinary team. Clinical governance arrangements should be made to allow continuous monitoring of FCGS provision and to facilitate auditing of the service. The request for FCGS may be reasonable and whilst we all respect the right to choose, there needs to be increased regulation in this controversial area of medicine.

References

1. Liao LM, Creighton SM. Requests for cosmetic genitoplasty: how should healthcare providers respond? BMJ 2007;334:1090-2.

2. Hospital Episode Statistics – Health and Social Care Information Centre:

www.hscic.gov.uk.

Accessed September 2013.

3. Yurteri-kaplan LA, Antosh DD, Sokol AI, Park AJ, et al. Interest in cosmetic vulvar surgery and perceptions of vulvar appearance. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;207:428.e1-7.

4. Braun V. In search of (better) sexual pleasure: female genital cosmetic surgery. Sexualities 2005;8:407-24.

5. Liao LM, Taghinejadi N, Creighton SM. An analysis of the content and clinical implications of online advertisements for female genital cosmetic surgery. BMJ Open 2012;2(6). doi:pii: e001908. 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001908

6. Goodman MP. Female cosmetic genital surgery. Obstet Gynecol 2009;113:154-9.

7. Mirzabeigi MN, Jandali S, Mettel R, Alter G. The nomenclature of “vaginal rejuvenation” and elective vulvovaginal plastic surgery. Aesthetic Surg J 2011;31:723-4.

8. Cain JM, Iglesia CB, Dickens B, Montgomery O. Body enhancement through female genital cosmetic surgery creates ethical and rights dilemmas. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2013;122:169-72.

9. Liao LM, Michala L, Creighton SM. Labial surgery for well women: a review of the literature. BJOG 2010;117:20-5.

10. Committee on Gynecologic Practice., American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee opinion No 378. Vaginal “rejuvenation” and cosmetic vaginal procedures. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:737-8.

11. World Health Organisation. Female Genital Mutilation. Fact sheet No 241. Updated February 2013.

12. Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003.

www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/

2003/31/pdfs/ukpga_20030031_en.pdf

13. Berer M. It’s female genital mutilation and should be prosecuted. BMJ 2007;334:1335.

14. Liao LM, Creighton SM. Requests for cosmetic genitoplasty: how should healthcare providers respond? BMJ 2007;334:1090-2.

15. Lloyd J, Crouch NS, Minto CL, et al. Female genital appearance: “normality” unfolds. BJOG 2005;112:643-6.

16. Rouzier R, Louis-Sylvestre C, Paniel BJ, Haddad B. Hypertrophy of the labia minora; experience of 163 reductions. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;182:35-40.

17. Crouch NS, Deans R, Michala L, et al. Clinical characteristics of well women seeking labial reduction surgery: a prospective study. BJOG 2011;118:1507-10.

18. Veale D, Eshkevari E, Ellison N, et al. Psychological characteristics and motivation of women seeking labiaplasty. Psychol Med 2013:1-12. [Epub ahead of print]

19. Iglesia CB, Yurteri-Kaplan L, Alinsod R. Female genital cosmetic surgery: a review of techniques and outcomes. Int Urogynecol J 2013 May. [Epub ahead of print]

20. Milkos JR, Moore RD. Labiaplasty of the labia minora: patients’ indications for pursuing surgery. J Sex Med 2008;5:1492-5.

21. Goodman MP, Placik OJ, Benson RH, et al. A large multicentre outcome study of female genital plastic surgery. J Sex Med 2010;7:1565-77.

22. Van Moorst BR, van Lunsen RH, van Dijken DK, Salvatore CM. Backgrounds of women applying for hymen reconstruction, the effects of counselling on myths and misunderstandings about virginity, and the results of hymen reconstruction. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2012;17:93-105.

23. Goodman MP. Female genital cosmetic and plastic surgery: a review. J Sex Med 2011;8:1813-25.

24. Hasan JS. Psychological issues in cosmetic surgery: a functional overview. Ann Plast Surg 2000;44:89-96.

25. Veale D, Eshkevari E, Ellison N, et al. Validation of genital appearance satisfaction scale and the cosmetic procedure screening scale for women seeking labiaplasty. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2013;34:46-52.

26. Rust J, Golombok S. The Golombock-Rust Inventory of Sexual Satisfaction (GRISS). Br J Clin Psychol 1985;24:63-4.

27. Mirzabeigi MN, Moore JH Jr, Mericli AF, et al. Current trends in vaginal labioplasty: a survey of plastic surgeons. Ann Plast Surg 2012;68:125-34.

28. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Clinical guideline 171. Urinary incontinence in women. Sept 2013.

http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/

live/14271/65144/65144.pdf.

Accessed 30 October 2013.

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.