Female genital mutilation / cutting (FGM/C), aka female circumcision, is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “All procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia for non-medical reasons” [1].

Practised in Africa and other parts of the world, the WHO recently estimated that over 250 million females have been circumcised so far, and an additional three million are at risk of circumcision each year, nearly 8000 cases a day [2].

First recorded in Egypt in the 5th Century BC, and noted on a papyrus from Memphis in 2nd Century BC, its historic background goes back more than 3000 years. Some ancient Egyptian mummies were found to have been circumcised.

FGM/C awareness has increased globally in the past 20 years, due to an increased influx of African immigrants and refugees, with 680,000 cases in Europe and 513,000 in the United States, putting a heavy burden on the healthcare systems of the host countries. It is a destructive procedure, criminalised by law in most countries, and considered a crime against humanity [3].

The area excised usually includes the:

- clitoris

- clitoral hood

- labia minora

- labia majora

FGM/C has no medical benefits, the reason for the practice is purely traditional with a false religious pretext in some cases. It is usually performed before puberty, but can be done at any age [4].

FGM/C in practising communities is regarded as:

- purification and cleanliness

- perquisite for growing into womanhood

- preserves virginity and family honour

- provides better marriage prospects for girls

- prevents promiscuity and adultery

- saves face for family within the community

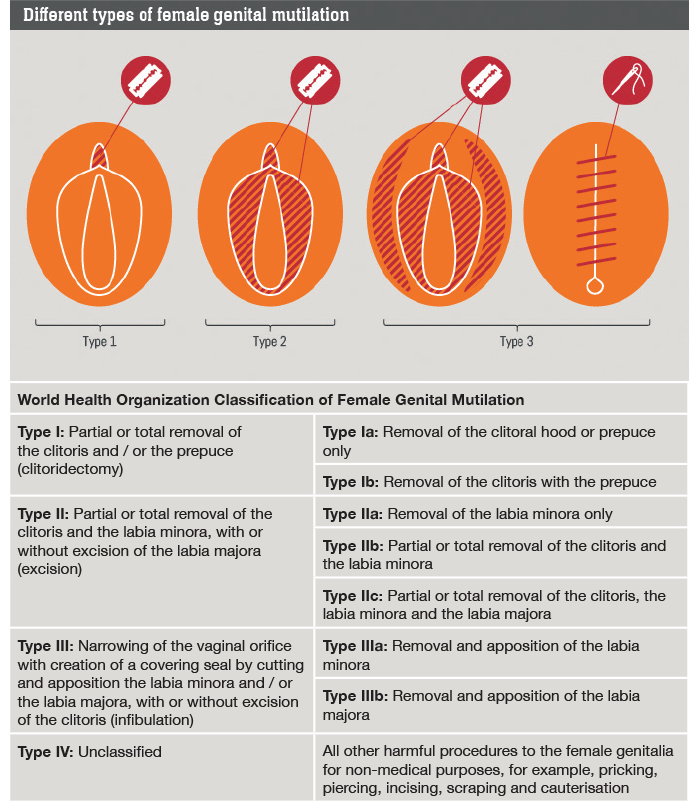

Figure 1: WHO classification of FGM.

Types: The WHO classifies FGM/C in four types (Figure 1) with varying degrees of cutting, ranging from a simple nick on the prepuce, clitoral excision, labial (minora and majora) amputation, to complete infibulation.

Under this classification, simple aesthetic gynaecology procedures such as labiaplasty and clitoral hood reduction are unjustifiably categorised as FGM.

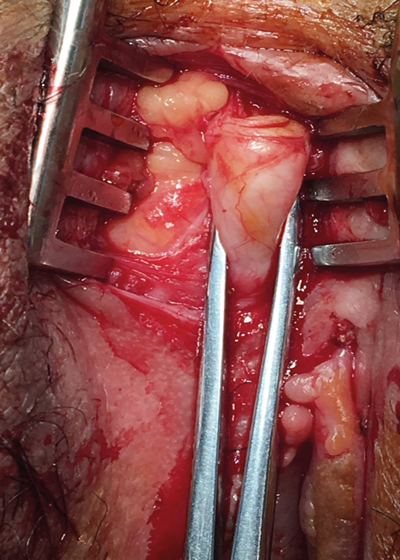

Figure 2: Pharaonic infibulation.

In some African communities, the clitoral body is partially excised and both labia (minora and majora) are cut and the skin gap is sutured together forming a covering skin seal acting as a chastity belt and creating a small opening at the lower end of the vagina for urine and menstrual flow (Figure 2). This is called Pharaonic infibulation, and in some cases the opening is too narrow to allow consummation of marriage and a surgical procedure known as defibulation is performed to open the vulva skin cover to allow sexual contact [5].

Complications of FGM/C:

- haemorrhage, neurogenic shock, sometimes leading to death

- infection by HIV, hepatitis and tetanus

- trauma to surrounding structures (urethra and vagina)

- implantation inclusion cysts, keloid and scar tissue formation

- decreased clitoral response in desire, arousal and orgasm

- increased materno-fetal morbidity and mortality during labour

- pain, dyspareunia and dysmenorrhea

- psycho-sexual disturbances: - low self esteem, shame, embarrassment with partner - post-traumatic stress disorder - anxiety and psychosomatic disorders - flash back to traumatic event

Management: The complexity of symptoms are best managed by a multidisciplinary approach provided by a group of gynaecologists, psychologists, midwives and social workers. Main guidelines are psycho-sexual assessment, sexual education, comprehensive physical exam, and surgery (defibulation and clitoral restoration) if needed [6].

Clitoral reconstructive surgery (CRS)

FGM/C victims still retain the ability to reach orgasm after clitoral excision, the clitoris is a highly sensitive organ and can be modified to function as a new clitoris [7].

a

b

Figure 3: a) Releasing clitoris from adhesions.

b) Mobilising clitoris by cutting suspensory ligament.

Although many FGM/C victims are unaware of the availability of genital reconstructive surgeries, the demand for genital reconstructive surgery both for functional and aesthetic reasons, has dramatically risen in past years due to increased patient awareness, better education, and modern aesthetic and sexual health trends (Figure 3).

Method:

- removing peri-clitoral adhesions

- releasing and mobilising the clitoris by cutting the suspensory ligament

- preserving the dorsal neurovascular bundle

- restoring clitoris to its normal anatomical position in the frenulum (if present).

Platelet rich plasma (PRP) injections, directly into the clitoris, improve clitoral sensitivity by increasing blood flow, growth factors and stimulating stem cells in the region [3].

Postoperative follow-up, counselling and reassurance provide a holistic management protocol for FGM victims.

Results: Our study included 107 patients; results vary from no improvement to 90% improvement in sexual desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm and decrease in pain. Better results were found in younger women with better education and higher socio-economic status. These marked improvements were especially noted in young adult women with type I and type II FGM/C, and probably attributed to the psychological benefits of the procedure, which may exceed the physical benefits [3].

Conclusion

FGM rates are declining globally due to changing socio-cultural and economic factors. Genital restorative surgeries have provided hope for FGM/C victims to regain their dignity, improve sexuality and quality of life. We have noted an improvement in aesthetic appearance and reported functional outcome, self-confidence, female self-image, partner and parent relationships after the procedure and support.

We therefore suggest that the clitoral reconstructive procedure should be made available to FGM/C victims. The possibility of such surgery should be more widely promoted in the community and also in hospitals when patients are presenting with aesthetic and sexual function complaints. Finally, it is important to be able to meet increased demand through the training of more surgeons in the art and practice of female genital reconstructive surgery.

References

1. World Health Organization, Department of Reproductive Health and Research (2008) Eliminating female genital mutilation: an interagency statement. OHCHR, UNAIDS, UNDP, UNECA, UNESCO, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNIFEM, WHO. World Health Organization, p Geneva.

2. WHO (2012) Female genital mutilation, Fact sheet N241. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

3. Seifeldin A. Genital reconstructive surgery after female genital mutilation. Obstet Gynecol Int J 2016;4(6):00129.

4. Foldès P, Cuzin B, Andro A. Reconstructive surgery after female genital mutilation: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 2012;380(9837):134-41.

5. Foldes P. Reconstructive surgery of the clitoris after ritual excision. J Sex Med 2006;3(6):1091-4.

6. Abdulcadir J, Rodriguez MI, Petignat P, Say L. Clitoral reconstruction after female genital mutilation/cutting: case studies. J Sex Med 2015;12(1): 274-81.

7. Thabet SM, Thabet AS. Defective sexuality and female circumcision: the cause and possible management. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2003;29(1):12-9.

Declaration of Competing Interests: None declared.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME