In the following article and case study, the condition of body dysmorphia disorder (BDD) is examined in the context of its pathogenesis and the role of the cosmetic practitioner. BDD is a problem that affects patients on a deeply personal level and some patients are particularly vulnerable to it partly due to bombardment of imagery on social media, TV, advertisements and various other forms of entertainment.

A person with BDD may be fixated on one particular physical flaw, or spend a disproportionate amount of time comparing their physical appearance with that of others. They may also spend an excessive amount of time looking in mirrors, or alternatively they may avoid mirrors completely. It should be kept in mind that BDD is a particular type of mental health condition that causes considerable psychological distress and severely impacts quality of life for the sufferer.

In this article, the author outlines a novel encrypted screening approach to detecting potential BDD in a non-surgical consultation that may help cosmetic practitioners in the important area of appropriate patient selection. The objective is to avoid applying surgical solutions to psychological problems.

Background

BDD is an increasingly recognised issue for cosmetic practitioners. Its incidence in the cosmetic setting is estimated to be between 5-15 times higher than that found in the general population [1]. However, surveys of practitioners have shown that it is severely underdiagnosed.

The author has had experience of one particularly challenging case and has since provided a BDD questionnaire (BDDQ) to all prospective patients. It was subsequently fed back by patients that they were uncomfortable being screened, and some refused to complete the questionnaire. More interestingly, however, several patients proposed the hypothesis that if someone with BDD was determined to be treated, the possibility of falsified answers must be considered.

The pathogenesis of BDD has been attributed to three key components by Weiffenbach et al [2]. These include multiple biological (i.e., neurological, genetic and impaired processing), psychological, and sociocultural factors. There are two internationally recognised diagnostic manuals: the International Classification of Diseases (ICD); and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Additionally, in the UK there are guidelines published by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), which in 2005 launched its own diagnostic guidelines for BDD [3].The role of the cosmetic practitioner, however, is to provide an effective screening tool and make sure that cosmetic solutions are not provided for psychiatric conditions.

Case report

A 42-year-old female presented to an aesthetic medical clinic for consultation. She had previously had three anti-wrinkle injection treatments in this clinic, having stated that the author was the only doctor who managed to ever do her Botox properly.

She was interested in dermal fillers for moderate mid-face ageing, including mild-to-moderate fat pad ptosis resulting in a deep pre-jowl sulcus and loss of jawline definition. During the consultation, she claimed she had previously attended a competing clinic one year prior for jawline contour but was dissatisfied with the result. Of note, the previous injector was a former colleague and injector of excellent repute.

She also disclosed various personal difficulties to the clinic manager in conversation, including the terminal illness of her mother and a legal dispute with a neighbour, which were causing her considerable distress.

Despite several ‘red flag’ signs, the patient said she had received dermal filler many times before and her expectations were realistic, reassuringly stating that she wasn’t expecting miracles. After a thorough facial assessment and discussion of a treatment plan, she was booked back in two weeks later to allow for a cooling-off period. Of note, she expressed an unusual knowledge of dermal filler brands, specifically asking for the Juvéderm Ultra range.

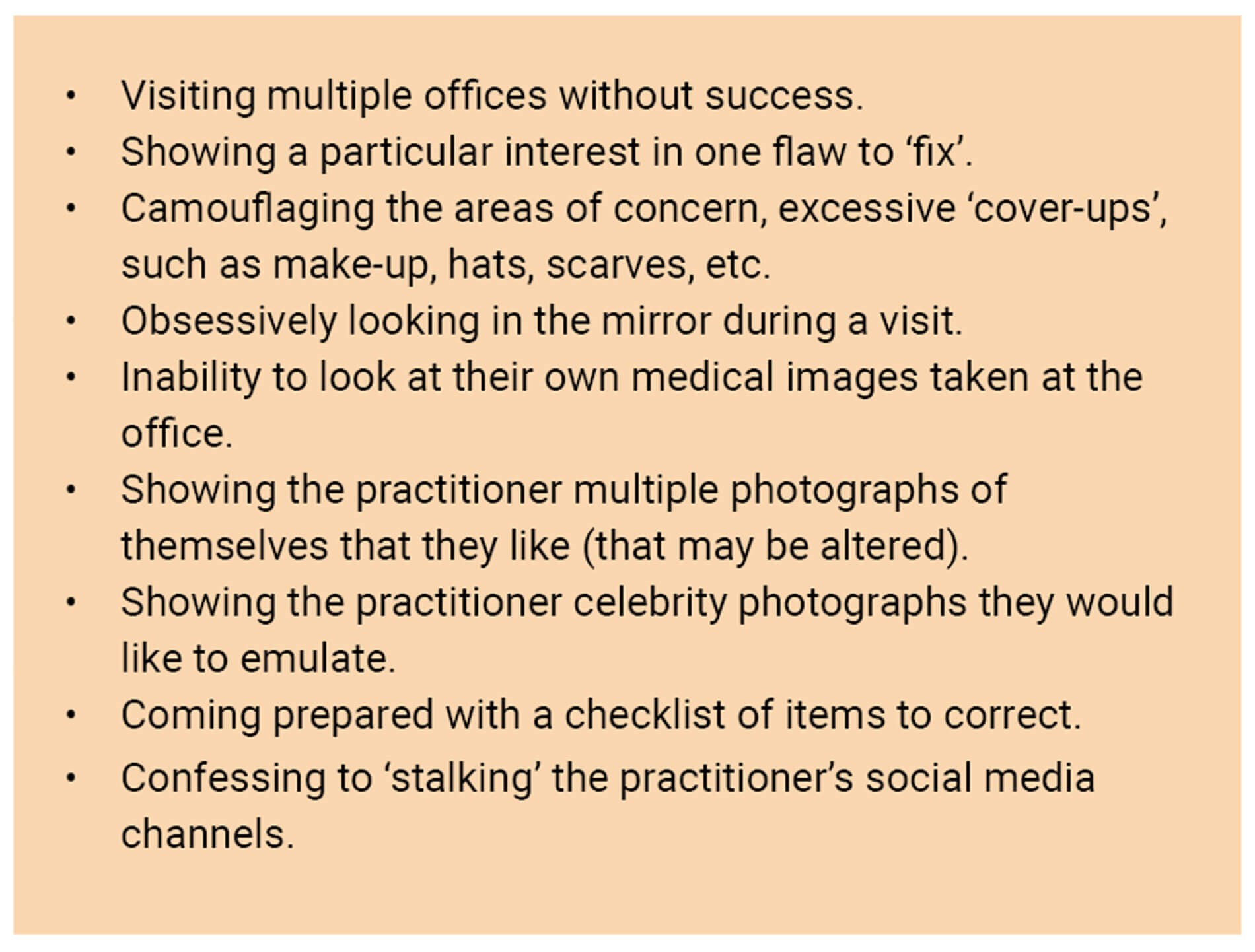

Figure 1: BDD ‘red flags’ during a consultation.

After her treatment was performed, she seemed pleased. However, she subsequently reattended the clinic on three occasions for review of an unsatisfactory aesthetic result and demonstrated a number of ‘red flags’, which are highlighted in Figure 1 above [4].

In our final conversation, it transpired the author was the fourth injector she had attended within 12 months. She subsequently wrote many irate emails, including instructional YouTube videos, demands for compensation and legal threats.

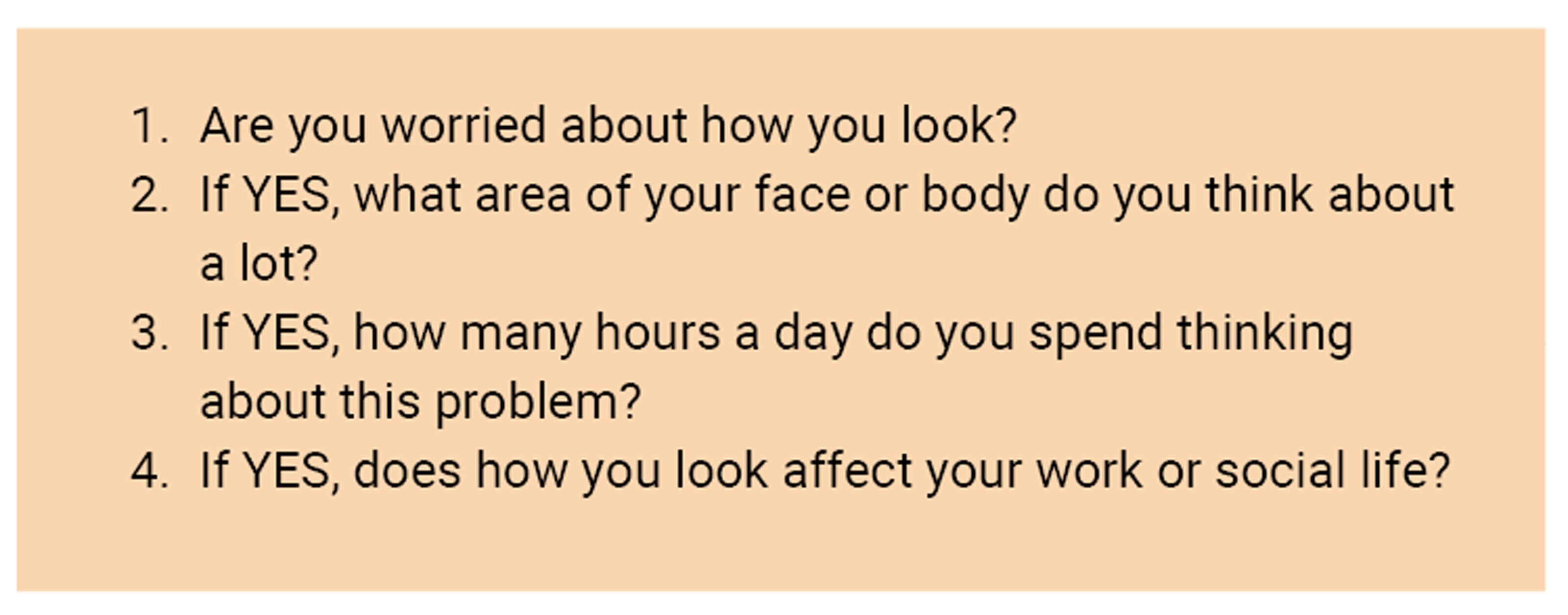

Figure 2: BDD screening questions for medical consent form.

Objective and method

The author aimed to create and apply a novel rapid screening tool to pick up potential underlying BDD characteristics in prospective patients presenting for aesthetic procedures. The author reviewed all current screening tools and chose from the BDDQ and NICE guidelines the four most pertinent questions to implement into the standard aesthetic medical consent form (Figure 2).

Each patient was given a standard three-page A4 aesthetic medical consent form. The consent form also contained four embedded questions in an untitled section of the questionnaire relating to body image dissatisfaction. Before entering the consultation room, the clinic nurse scanned each consent form and flagged any patient who had answered ‘YES’ to any of the four questions and alerted the doctor to the positive finding before ushering in the patient.

Results

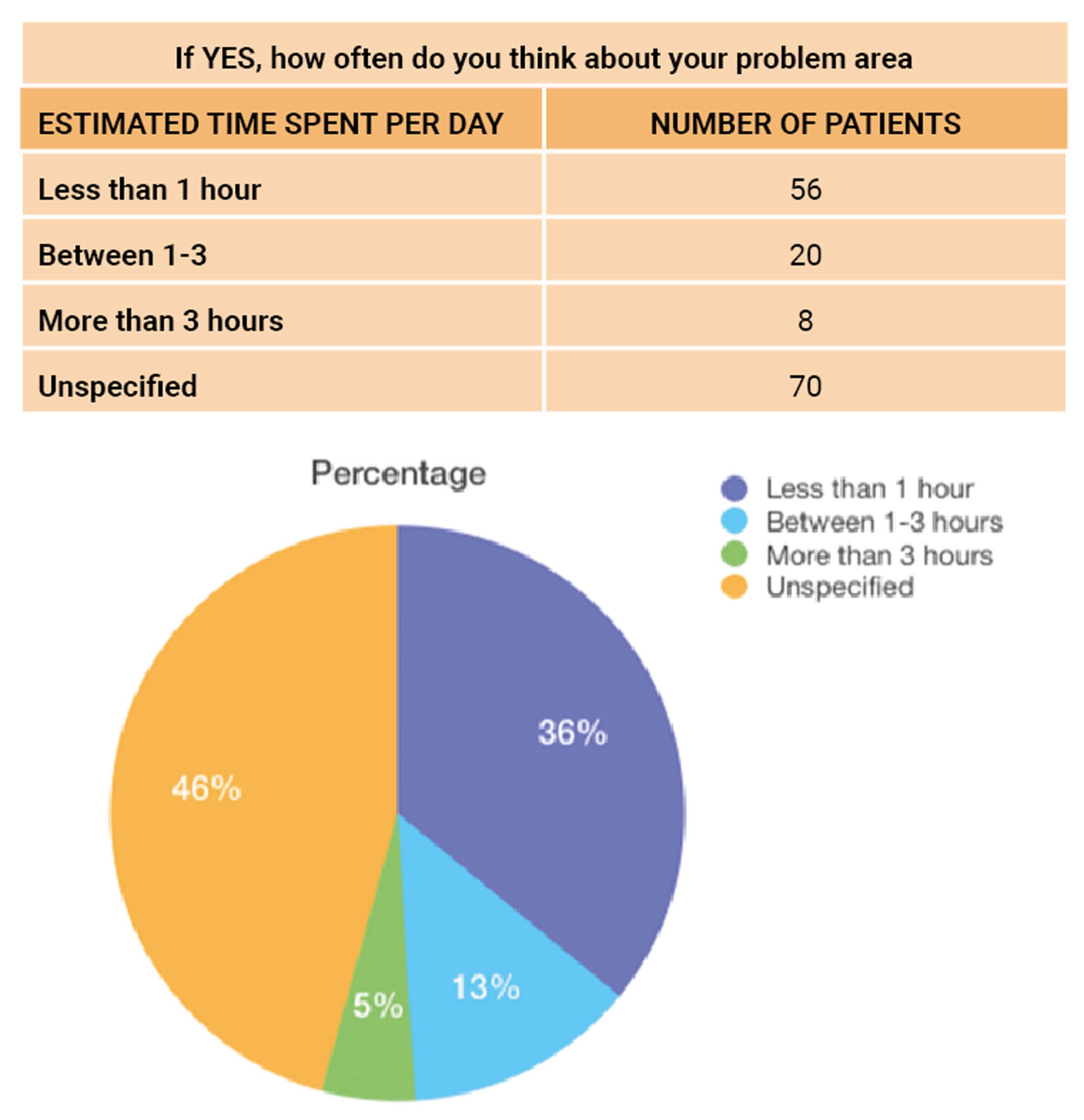

Over a six-month period across three different clinics in the greater Dublin area, the total sample size of participants was n=488. Of the total respondents, 335 said ‘NO’ to Question 1 (‘Are you worried about how you look?’), while 153 said ‘YES’. Seventy patients did not specify how long they spent thinking about their body part / parts. Fifty-five said they spent less than an hour per day, 20 patients spent one to three hours, and eight patients spent more than three hours thinking about the body part / parts (Figure 3). Only three patients declared that the way they looked affected their work or social life. The most common areas identified by respondents as causing concern were the upper face, under eye area and body shape.

Figure 3: Synopsis of results for question, ‘If YES, how often do you think about your problem area?’

Discussion

In a 2015 meta-analysis, it was shown that suicidal intent among patients with BDD is four times higher than seen in the general population [5]. It is therefore the responsibility of aesthetic practitioners to choose a suitable method for BDD screening and take the necessary steps to evaluate further when required. Its importance is underpinned by the knowledge that BDD patients will rarely be satisfied with the cosmetic treatments they receive and have a marked increased risk in both suicidal thoughts and threatening behaviour towards their provider. The initial exposition on BDD by Katharine Phillips [6] provides a comprehensive overview of the scope, scale and treatment options for BDD. Several different questioning tools are available and with appropriate use will provide the practitioner with a useful tool for screening patients. Blackburn and Blackburn [7] produced a more indirect assessment tool based on questioning the patient – the SAGA mnemonic – to assess the background and reactions of the patient. This may also provide an alternative method to be of use in the clinical setting.

Conclusion

In this article and case study, the author has proposed a novel screening tool that may help aesthetic practitioners to identify patients who may suffer with BDD and are seeking a surgical solution to their issues. The screening tool helps practitioners to evaluate certain behavioural aspects of the patient in a non-surgical consultation. Part of this process is to help determine how the patient’s self-perception is impacting their lives, both personally and professionally.

The screening tool includes targeted questions contained in a medical consent form. The clinic nurse then scans the form, and if ‘YES’ is answered to any of the four basic questions, the cosmetic practitioner is advised of the results before the patient is given access to the consultation. This study shows how cryptic questioning can be effective in flagging potential BDD during the non-surgical cosmetic consultation.

As illustrated in the article, many patients with BDD may have undergone a number of previous procedures and expressed displeasure with the results on each occasion. Taken to its extreme, this can result ultimately in legal difficulties for the practitioner. The case study illustrates how some patients with potential BDD may threaten legal action, or even ‘stalk’ their practitioner via social media. The proposed novel screening tool outlined above may be helpful for aesthetic practitioners in the vital area of patient selection.

References

1. Aouizerate B, Pujol H, Grabot D, et al. Body dysmorphic disorder in a sample of cosmetic surgery applicants. European Psychiatry 2003;18(7):365-8.

2. Weiffenbach A, Kundu R. Beauty and Body Dysmorphic Disorder 1st Ed Boston, MA, USA; Springer International PU: 2016.

3. NICE. Obsessive-compulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorder: treatment. 2005.

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg31

[accessed 22 June 2023].

4. Fletcher L. Development of a multiphasic, cryptic screening protocol for body dysmorphic disorder in cosmetic dermatology. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology 2021;20(4):1254-1262.

5. Angelakis I, Gooding P, Panagioti M. Suicidality in body dysmorphic disorder (BDD): A systematic review with meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review 2016;49:55-66.

6. Phillips KA. The Broken Mirror 2nd Ed. Oxford, UK; Oxford University Press: 2005.

7. Blackburn VF, Blackburn AV. Taking a history in aesthetic surgery: SAGA – the surgeon’s tool for patient selection. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery 2008;61(7):723-9.

Declaration of competing interests: The author is a trainer with the RELIFE Ireland affiliate and has been paid by the company to write this article. The company had no input into the content of this article. The research was carried out as part of an MSc dissertation and ethical approval was not required.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME