By Professor Andrew Burd

1 April 2020. It is past midday so this is real. Just under three weeks ago, 9 March, I was invited to write a guest editorial for the Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery. I described the impact of SARS on surgery. I will share some of this with you, but I will keep this first letter short and focus on two things: fear and masks.

1. Fear

I do not know how many of you are familiar with a gentleman called David Icke. David was born in Leicester in the same year I was born in Bristol. David went onto become a football player, a manager and ultimately a writer. His particular genre is conspiracy theories. David very publicly called me out suggesting I was guilty of hyperbole when expressing my fear in March 2003.

Let me put it in context. The world had been put on standby that a mighty coalition force was gathered on land and sea around Iraq with the intention of overthrowing the regime of Saddam Hussein. The ‘justification’ for this war was that Saddam had weapons of mass destruction and he had to be stopped from using them. The world waited with bated breath. What were these weapons of mass destruction?

10 March 2003 was a Monday. One of our all-day plastic surgery lists, and we were embarking on a big case. I was operating with my dear friend, the great Indian orthopaedic surgeon, Shekhar Kumta. We were dealing with a girdle tumour (Figure 1). These are not simple operations and we wrote up a series a few years later [1].

Figure 1: Professors Kumta and Burd and the plastic surgery team.

What we did not know then was that just a few weeks before, on 23 February, a 64-year-old doctor from Guangzhou had been visiting Hong Kong and stayed at the Metropole Hotel. He had been in contact with several people, including a 29-year-old man who was admitted to the Prince of Wales Hospital on 4 March. It is estimated that at least 99 hospital staff, including 17 medical students became infected whilst treating that 29-year-old. On the 12 March 2003, WHO issued a global alert about a new infectious disease and thus the ‘severe acute respiratory syndrome’ (SARS) was born. That week was like no other I have ever experienced. I had friend in the BBC, and he phoned me up. I told him what was going on and the BBC published a news feature based on this: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/2851487.stm

I am going to quote some of the feature directly:

“On Thursday morning (that would have been the day after the WHO global alert), we had the first evidence that we were all in the front line. Arriving for the early morning round we were given facemasks and told to wear them. These were no ordinary surgical masks, but the all-enveloping masks worn by the DIY fanatic who is building up a dust storm on a British Sunday afternoon with his sander.

As we trailed from ward to ward to visit our patients, we saw more and more staff wearing these bright green masks.

We felt somewhat self-conscious and joked about alien dust and then sat in offices and took the masks off and wondered what it was all about.”

We did not know what was going on and it was difficult initially to process information that seemed somewhat abstract from our personal experience. But then within days, we had over 60 cases with 40 of them being medical staff and students. The ICU was full and we stopped making jokes about masks.

My comments in 2003 concluded thus:

“We have colleagues fighting for their lives. We have an invisible killer in our midst. We are professionals and we have a job to do. Now, as I sit at home with my young son quietly sleeping and my wife pottering in the background, I wonder what tomorrow will bring? We are at war, but our enemy has no name, no identity.

This reality easily eclipses the nightmare fantasies of Bush and Saddam. For the moment, Iraq is no longer an issue in Hong Kong. “

Our fear was real. Your fear will also be real. And this is where David Icke comes in. He read the bit in the BBC and I was annoyed by his dismissive comments. It is easy to see things differently when we look back or look from afar. Fear of the unknown, is something you experience in the present when looking forward. We all experience fear and the fears will be different. As professionals we should be able to compartmentalise our fears in order to get the job done. But that does not remove the fear, and it is still essential to remain connected with others and find time to share concerns. Our children, elderly relatives, finances, food, our ability to cope and the ability of the system to survive. We should embrace our fears, own them, share them and overcome them.

2. Masks

It is more than just masks. I am now morphing from a paediatric burns surgeon to a post-graduate student in public health working in the field of epidemiology. What an incredible time to be finishing off the final revisions of my PhD (oral defence passed). My PhD has been looking at the epidemiology of burns in Hong Kong. A key point for me is precision in language and when there are terms open to multiple definitions, I like to define my use. There is a great difference when comparative data is presented solely on the basis of geography and when it is presented on the basis of human behaviour and geography. The key elements for me with regard to epidemiology is that it is the science which studies the distribution and determinants of health-related conditions, in a defined population, and the use of that knowledge to address the challenges of that condition. We need data to demonstrate associations / correlations which support the identification of possible determinants that can give clues to preventing the dissemination of the ‘disease’.

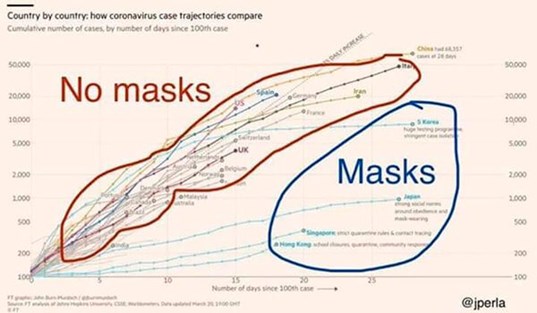

There is now a figure being shared on the web of the patterns of the increase in cases in countries over the world and the patterns are very different between those countries where people wear masks and those that do not.

Figure 2.

I was watching the infomercial on the BBC website talking about the need to “cough into a tissue” when in public. Looking at the WHO website they talk about how the public should behave, and I quote:

“Maintain social distancing

Maintain at least 1 metre (3 feet) distance between yourself and anyone who is coughing or sneezing.

Why? When someone coughs or sneezes they spray small liquid droplets from their nose or mouth which may contain virus. If you are too close, you can breathe in the droplets, including the COVID-19 virus if the person coughing has the disease.”

The problem is described but the solution is not. The spray from a cough or sneeze can spread more than one meter. What is need is to stop the spray at source and THAT is the reason why everyone in the public should be encouraged to wear masks. These are not the N95 mask, a fine thread, folded cotton handkerchief tied like the wild west bank robbers would be effective if they gave the right message. Cough responsibly.

Healthcare workers, who are having to deal with potential virus carriers, need more protection and this is where the fitted N95 mask comes in. These should be worn in conjunction with safety glasses, shields or goggles to protect the eyes. You do not need to change the N95 between patients in general clinics and I can recall we were all provide with brown paper bags to put our masks in after our ‘shifts’. When science does not have a convincing answer as to best practice, common sense is an alternative. There is no need to ‘burn’ through massive stocks of PPE unless it is no longer protecting the health professional or the patients they are treating.

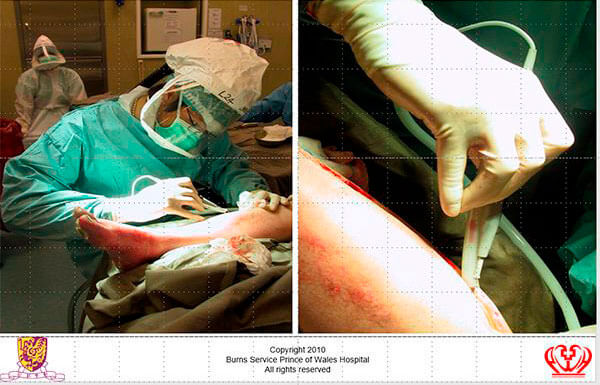

The third type of mask is shown in the next figure. This shows a case of decompression in the time of SARS. Performing surgery on an infective case requires an even greater level of care. Decompression of a burn, in theatre, should be performed by diathermy set on coagulation mode [2]. This will create an aerosol (smoke) which is far more intrusive than droplets. In our case each surgeon, anaesthetist and nurse had their own personal respirator with the input being a high specification filter.

Figure 3: Protection from potentially infected aerosol.

We got through SARS but it did need radical changes in the ways we worked. There were also radical changes in the way people behaved within Hong Kong. It became a ghost city for a while. Social distancing, wearing masks, frequent hand washing and obsessive cleaning. Healthcare workers are now at particular risk and must be protected. How countries fare in this current crisis will be a function of the effectiveness of the respective public health disciplines, but also the honesty of the politicians. This is not a warning. This is not a drill. It is the real thing and I hope and pray that humanity will be able to hold it together long enough to get through this. When we do, I think I must look up David Icke and see how he fared. I wish him, and I wish you all, well.

References

1. Burd A, Wong KC, Kumta SM. Aggressive surgical palliation for advanced girdle tumours. Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery, 2012;45(1):16-21.

2. Burd A., Noronha FV, Ahmed K, et al. Decompression not escharotomy in acute burns. Burns 2006;32(3):284-92

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME