I was recently attending a national aesthetics conference when I got talking to a very well-known opinion leader in the aesthetics world. During the conversation, I was astounded to be asked: “What do you think now that NICE has agreed that varicose veins can be treated in aesthetic clinics?” I was at a loss for words, which is a rare experience for me! I thought there must have been some new guidelines that I was unaware of, because the most recent National Institute for Health & Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines say nothing of the sort [1].

So I asked this person if they had actually read the guidelines and, if so, where in the document did this assurance lie? Light dawned when the person in question confessed that they hadn’t actually read the NICE Guidelines themselves, but assured me that “everyone was talking about it”!

With the increasing numbers of aesthetic clinics starting to offer vein services, it is clearly being seen as a growth area. Hence I can see why such rumours are going around the aesthetics world. There is a French phrase that sums this sort of behaviour up ‘Folie à Deux’. It is human nature that when people are unsure of something that they want to do, they often ‘bounce’ ideas off their peers. When they then hear the same idea coming back from others, they feel reassured that it is OK – even though they started the idea off themselves.

In the current era of increasing litigation in the UK and as a recognised vein expert who is seeing increasing numbers of patients upset with the results of poor vein treatments from different providers of ‘vein treatments’, this now seems an opportune time to discuss what the NICE guidelines actually say and to share some of the current research into vein treatments.

Before going through the NICE Clinical Guidelines, there are two very important concepts that need to be understood by anyone planning to enter the vein world.

Figure 1: Picture of varicose veins of left leg showing para-vulvar varicose veins at the upper inner thigh – signifying pelvic vein reflux. This patient needs leg and transvaginal duplex ultrasound scanning to plan treatment.

Concept 1: aesthetic clients vs. varicose veins patients

In aesthetics, the vast majority of people coming to see you are fit and healthy. They are not sick and do not have a medical problem. They are asking for a service and hence are clients. The area they want treated is usually localised to the area that they indicate.

Conversely, patients with varicose veins have a medical condition. Venous reflux disease (the underlying cause of varicose veins) is a systemic condition, affecting blood vessels remote from the area that the patients point out to you as the ‘problem’ [2]. Research has shown the link between leg varicose veins and pelvic vein reflux via vulval / vaginal varicose veins [3] (Figure 1), haemorrhoids [4] and dilated coronary arteries [5].

Hence, varicose veins patients are not clients, but are patients with a medical condition of their circulatory system – and if you take responsibility for assessing and treating them, then you need to be certain that you have the knowledge and facilities to do so, including the complications that might arise from your treatments in both the short and long-term.

Concept 2: assessment of what to treat

Aesthetic clients show you what they don’t like or what they want to change. This might be unwanted hair, skin discolouration, skin laxity or wrinkles, contour changes – either needing filling (using fillers) or removal (such as liposuction) or other ‘problem areas’. However, what virtually every aesthetic problem has in common is that it is local to the area involved and can be assessed visually. Moreover, treatments can usually be planned on a visual assessment alone.

Venous reflux disease is totally different. Although the manifestations might be seen in one area, such as a patch of thread veins or a varicose vein on the leg, the underlying cause of the venous reflux is not local to this area and cannot be seen on the surface. Indeed, the latest research has been shown that the underlying cause isn’t just restricted to the two main veins that are usually thought to be the problem (the great and small saphenous veins) but by studying recurrence after inadequate treatment has shown that underlying causes are often the anterior accessory saphenous vein [6], incompetent perforating veins [7] and / or pelvic veins [8].

Almost none of these underlying veins can be seen on the surface, although some clues can be seen by the experienced eye (Figure 1) – hence it is impossible to adequately assess and treat veins patients by a visual assessment alone.

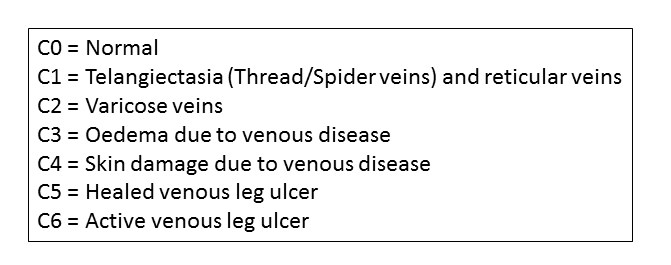

Figure 2: Clinical Score of the CEAP Scoring System.

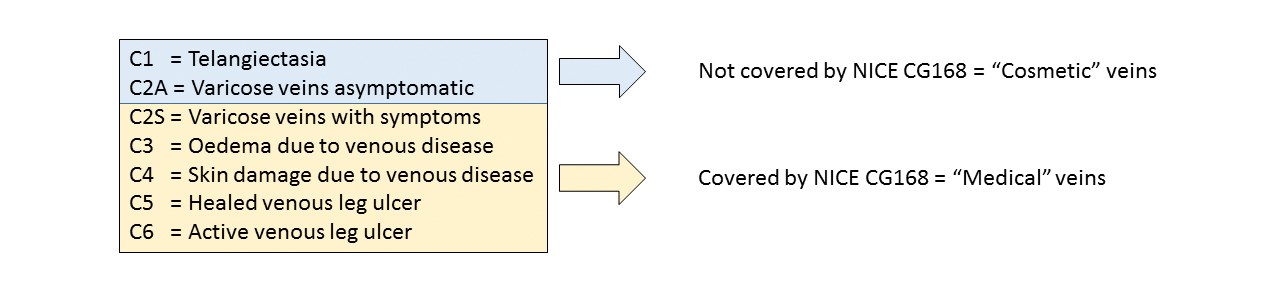

Figure 3 (Below): Veins separated into ‘cosmetic’ veins and ‘medical’ veins by Clinical Score.

NICE Clinical Guidelines 168 only cover the medical veins.

So what does NICE actually say about veins?

NICE produced their Clinical Guidelines (CG 168) for: ‘Varicose veins in the legs: The diagnosis and management of varicose veins’ in July 2013 [1].

Firstly, and very important for aesthetic practitioners to know, these guidelines deal with varicose veins that are causing symptoms or signs of venous disease. The NICE Guidelines do NOT cover thread veins (telangiectasia), reticular veins or varicose veins that aren’t causing any symptoms or other problems.

In the venous world we grade these different clinical entities by using a sort of short-hand. We use the clinical part of the Clinical Etiological Anatomical and Pathological (CEAP) score (Figure 2).

Using this grading system we can split the rest of this article into ‘cosmetic veins’, or more scientifically C1 and C2A veins, and ‘medical varicose veins’ C2S and C3 – C6 (Figure 3).

As this section is about the NICE guidelines for varicose veins, we can ignore the cosmetic veins (C1 and C2A) for now and we will come back to these later.

So what does NICE say about varicose veins C2S-C6? NICE CG168 tells us:

- What information you should be giving every patient with varicose veins

- Which patients should be referred for assessment

- Where they should be referred to

- What treatments they should be offered.

What should you be telling patients with varicose veins?

As with all patients that you see, you need to be able to inform your patients fully about their conditions and any treatments they could have for them to be able to consent to having treatment with you.

NICE states that you must provide information as to:

- What varicose veins are

- Possible causes

- Likelihood of progression

- Possible complications.

You also need to:

- Address any misconceptions about risks of developing complications

- Explain treatment options (symptom relief, an overview of interventional treatments and the role of compression)

- Give advice on weight loss, physical activity, factors that are known to make their symptoms worse and when and where to seek further medical help

- Tell the patient what treatment options are available (not just the treatment option you are offering)

- Explain the expected benefits and risks of each treatment option

- Explain that new varicose veins may develop after treatment

- Explain that they may need more than one session of treatment

- Explain that the chance of recurrence after treatment for recurrent varicose veins is higher than for primary varicose veins.

Which patients should be referred for assessment?

As NICE guidelines do not cover patients with ‘cosmetic’ vein problems, the criteria for referral reflect the medical nature of varicose veins. So if you are setting up a vein service, you need to be able to deal with these.

Criteria for referral:

- Bleeding varicose veins (need to be referred immediately)

- Symptomatic primary varicose veins

- Symptomatic recurrent varicose veins

- Lower limb skin changes (such as pigmentation or eczema)

- Superficial vein thrombosis (characterised by the appearance of hard, painful veins)

- A venous leg ulcer (a break in the skin below the knee that has not healed within two weeks)

- A healed venous leg ulcer.

The symptoms stated in the guidelines are said to be “typically pain, aching, discomfort, swelling, heaviness and itching.”

Where should varicose vein patients be referred to?

NICE is very clear about where patients with varicose veins should be referred to for assessment and treatment. In NICE CG168, all patients who need referral should be seen in a ‘vascular service’.

So what is a vascular service? In the context of assessing and treating varicose veins, NICE defines a vascular service as: “A team of healthcare professionals who have the skills to undertake a full clinical and duplex ultrasound assessment and provide a full range of treatment.”

For those wanting to treat varicose veins there are several points that need to be taken from this quite simple definition:

- There needs to be a “team of healthcare professionals.” This is not one doctor who does a session or two of veins in a clinic.

- The team needs to “have the skills to undertake ... duplex ultrasound assessment.” Hence, a doctor doing their own duplex scans doesn’t fit with the team required and research presented in New York in 2013 showed that doctors doing their own scans missed at least 30% of the underlying causes of varicose veins.

- A service needs to be able to “provide a full range of treatment” which, as a very minimum, would need to be endovenous thermoablation, ultrasound guided foam sclerotherapy and phlebectomies with the ability to scan for deep vein thrombosis.

Which treatments should be used?

NICE CG168 suggests that the optimal treatment is endothermal ablation, which they note is catheter based radiofrequency ablation or endovenous thermal ablation. If these are not available or suitable, ultrasound guided foam sclerotherapy is next best. Only if both of these are not available or suitable should stripping be performed – and in the last decade I have not had a single patient that requires this.

Assessment and treatment of ‘cosmetic’ leg veins

So what about the C1 and C2A veins? These are the veins that are usually looked at by aesthetic clinics wanting to start a veins practice. NICE does not cover these, but of course patients are protected by the law, and doctors and nurses are restricted by the requirement to act within their own competency and in the best interests of the patient.

Taking the conditions in reverse order, C2 are varicose veins without symptoms. All varicose veins have underlying venous reflux causing them, so they cannot be assessed without a duplex ultrasound scan. Although not covered by NICE directly, it is clear that for a doctor or nurse to act within their competency, then such a scan should be performed by a specialist who is part of a vascular service.

C1 veins (thread or spider veins, or medically called telangiectasia) have also been shown to have underlying venous reflux from reticular feeding veins in 89% [9], truncal vein reflux in 46% [10], and incompetent perforating veins in 15% [9]. It is impossible to identify the 11% that do not have underlying venous reflux without a duplex scan.

Turning to treatments, the treatment of C2A and C1 veins is the treatment of the underlying venous reflux first and then the visible veins on the surface. Therefore, for the most basic treatment there is requirement for radiofrequency ablation / endovenous laser and / or ultrasound guided foam sclerotherapy in a majority of these patients.

Veins as a ‘business opportunity’

Leg vein problems are very common, with 88% or women and 79% of men showing leg telangiectasia [11]. As such, many business minded aesthetic clinic owners see this as a good market to aim for – often stimulated by companies trying to sell devices for facial thread veins and claiming that they “do leg thread veins as well.”

However, as described above, people turning up with leg vein problems are patients and need to be treated with the understanding that there is probably an underlying condition. In order to treat these patients properly, aesthetic clinics need to either set themselves up as vascular services or have business links with established vascular services that have the required professionals, skills, protocols and equipment. Those in the aesthetics field are often shocked at the low profit margins realised as they see the prices being charged per procedure but not the costs of setting up such a vascular service with the required Care Quality Commission (CQC) registration, professional salaries, emergency cover and disposable equipment required.

Conclusions

To return to the original comment that started this article, the NICE Clinical Guidelines definitely do not state that varicose veins are now a cosmetic condition. In fact, it is quite the reverse, with the NICE recommendations showing that all patients with varicose veins of C2S or worse need to be referred to a vascular service.

C1 and C2A or cosmetic varicose veins are not covered by NICE. However, research exists showing that even these need to be treated as medical conditions, with all being scanned by a competent specialist as part of a team in a vascular service. Failure to do so would put any doctor and nurse involved into a position of potentially not acting within their competency and within the best interest of the patient.

With increasing litigation in medicine, aesthetic clinics taking on vein service need to be sure that they either comply with the definition of being a vascular service or form business relationships with recognised vein clinics, which do comply with these definitions. These can then perform the required assessments, treat any underlying conditions and then return the patient for treatment of the surface cosmetic problem.

References

1. Varicose veins in the legs: The diagnosis and management of varicose veins. National Institute of Health and Care Excellence.

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/

cg168/chapter/1-recommendations

Last accessed April 2015.

2. Mark Whiteley: Understanding Venous Reflux – The Cause of Varicose Veins and Venous Leg Ulcers. Whiteley Publishing Ltd: 2nd edition 2013.

3. Marsh P, Holdstock J, Harrison C, et al. Pelvic vein reflux in female patients with varicose veins: comparison of incidence between a specialist private vein clinic and the vascular department of a National Health Service District General Hospital. Phlebology 2009;24(3):108-13.

4. Holdstock JM, Dos Santos SJ, Harrison CC, et al. Haemorrhoids are associated with internal iliac vein reflux in up to one-third of women presenting with varicose veins associated with pelvic vein reflux. Phlebology 2015;30:133-9.

5. Yetkin E. Hemorrhoid, internal iliac vein reflux and peripheral varicose vein: Affecting each other or affected vessels? Phlebology 2015;30:145.

6. Garner JP, Heppell PS, Leopold PW. The lateral accessory saphenous vein - a common cause of recurrent varicose veins. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2003;85(6):389-92.

7. Whiteley MS. Part one: for the motion. Venous perforator surgery is proven and does reduce recurrences. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2014;48(3):239-42.

8. Whiteley AM, Taylor DC, Dos Santos SJ, Whiteley MS. Pelvic venous reflux is a major contributory cause of recurrent varicose veins in more than a quarter of women. Journal of Vascular Surgery: Venous and Lymphatic Disorders 2014:2(4);411-5.

9. Somjen GM, Ziegenbein R, Johnston AH, Royle JP. Anatomical examination of leg telangiectases with duplex scanning. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1993;19(10):940-5.

10. Engelhorn CA, Engelhorn AL, Cassou MF, Salles-Cunha S. Patterns of saphenous venous reflux in women presenting with lower extremity telangiectasias. Dermatol Surg 2007;33(3):282-8.

11. Ruckley CV, Evans CJ, Allan PL, et al. Telangiectasia in the Edinburgh Vein Study: epidemiology and association with trunk varices and symptoms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2008;36(6):719-24.

Declaration of competing interests: The author is a venous surgeon who runs a vein clinic that complies with the NICE CG168 definition of a ‘vascular service’.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME