Poly Implant Prothese (PIP) was a French company that manufactured silicone breast implants that were surgically implanted mainly for cosmetic breast augmentation. Of note, ‘cosmetic’ is used in the strict sense of the word meaning false and artificial and does not imply any medical need or health benefit. When silicone is implanted into the body a special medical grade silicone should be used.

This requires a higher form of preparation and incurs greater costs in manufacture than non-medical grade silicones. It was a significant act of self-deception when the owners of the PIP company thought that they could save costs and increase profits by using an industrial grade silicone rather than the medical grade silicone in the manufacture of their breast prostheses. Who would know about the substitution? Ultimately it was the unacceptably high rupture rate of the PIP implants that led to the downfall of the company and a worldwide scare that induced a range of responses from different national governments and regulatory bodies.

By 2011, the French government was recommending that 30,000 French women should have their implants removed. Who by, who pays, are they replaced, who by, who pays? A recommendation is easy to make but the logistics of implementation are very different. The subsequent fallout from the ‘PIP scandal’ is still playing out, but one of the outcomes is the Review of the Regulations of Cosmetic Interventions. This was the public face of the Department of Health demonstrating their concern about a massive industry that appears to be growing Hydra-like with seemingly little control or regulation. Prof Sir Bruce Keogh KBE, the National Medical Director for the NHS in England chaired a review committee that produced its report in April of 2013. Ms Judy Evans is commenting on this report in this issue (A Reaction to the ‘Keogh Report’ – page 22 of PMFA NEWS Oct/Nov 2013) and I will make no detailed remarks about the report here apart from the fact that I think it is an example of an opportunity wasted.

Surely the first part of any such report should be a definition of terms, but the report, supposedly on cosmetic interventions, jumps from surgical operations to medical procedures to non-medical and beauty treatments.The definition as stated in the glossary of the report is thus: ‘Cosmetic intervention: operations or other procedures that revise or change the appearance, colour, texture, structure, or position of bodily features, which most would consider otherwise within the broad range of ‘normal’ for that person.’ This is really so imprecise it relegates the recommendations within the report to mere political gestures, which have little moral, ethical or professional substance.

...whilst there may be a common view about how the service should be delivered, there is no such common ground about recognising who should deliver the service.

The whole issue is further trivialised by bringing up the analogy with purchasing a ballpoint pen or toothbrush and then by this very strange figure of speech appearing at the bottom of page five of the report: ‘These recommendations are not about increasing bureaucracy but about putting everyone’s (sic) safety and wellbeing first.’ So, in my opinion the Review panel has put in a lot of work to deliver a marginal performance and must try to focus more in the future.

Figure 1: This is the poster advertising the public lecture given by Mr Rana Das-Gupta.

Unfortunately the nursing hierarchy in the hospital took exception to the theme

of the symposium and the nursing staff were told not to attend.

The problem is that whilst there may be a common view about how the service should be delivered, there is no such common ground about recognising who should deliver the service. Unfortunately, the medical profession, or perhaps more correctly, a small number of specialists, appear to want to put their financial well being first and foremost when considering control and regulation. I am a little weary of the oft-repeated mantra of the less mature surgeons regarding the need to restrict interventions to only those for which the practitioner can manage all relevant complications.

This is a spurious justification for surgeons who want to try and control the lucrative dermal filler market. But it is fundamentally wrong. Mr Chris Munsch, a Consultant Cardiothoracic Surgeon and Past Chairman of the Joint Committee on Surgical Training for the Royal Colleges of Surgeons, was involved in compiling Appendix four: recommendations regarding training and education in cosmetic surgery, and here is recommendation number one:

Recommendation number 1: ‘The only person who should carry out cosmetic surgery is a doctor, fully trained in the technical, professional and cognitive aspects of the practice, and competent to handle any complications that may arise.’

It sounds reasonable until you consider the reality of medicine and in order to put an abrupt stop to a faulty line of reasoning we just have to ask how many of Mr Munsch’s interventional cardiology colleagues are competent in performing open heart surgery in the event of a complication with, for example, a coronary angioplasty that requires an emergency coronary artery bypass graft (<3% of cases)? It is also important to question the gobbledygook terms “technical, professional and cognitive aspects of the practice”. I have to raise these issues so that we do not move ahead thinking that all is well. All is not well and there is still much work to be done in the UK to bring all relevant parties together and in a fair and balanced manner find a solution to what all sectors of the industry accept is not acceptable.

There is still much work to be done in the UK to bring all relevant parties together and in a fair and balanced manner find a solution to what all sectors of the industry accept is not acceptable.

Meanwhile back in Hong Kong, the PIP saga did not really hit the headlines, but chance would have it that a crisis of another sort was about to unfold. There is a cutting edge and still largely experimental treatment that is offered to certain patients with malignant disease. DC-CIK immunotherapy can kill residual cancer cells. DC stands for dendritic cell, which is the most powerful antigen-presenting cell in the body. The cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cell is the lymphocyte. A peripheral blood sample can be taken from a patient and sent to a laboratory where the cells will be sorted and then a select population can be cultured and expanded.

The lymphocytes can be stimulated using specific antigens and subsequently, when re-injected into the blood stream, these new supercharged immune cells will seek and destroy any residual cancer cells. Essentially a very safe treatment, as the cells are autologous and as long as the culture takes place in a Good Manufacturing Practice accredited or compliant facility, everything should be okay. And so it was probably on this basis of a novel application for a hypothetical health benefit with low associated risk that the DR Beauty Centre chain started to offer it as a ‘wellness’ treatment. Of note, the owner of the chain is a medically qualified doctor and all procedures involving the client were performed by doctors. Apparently 40 or so treatments were performed with no adverse effect and then four clients became seriously ill and one of them died.

The responses from ignorant spokespeople from various sectors of the industry were predictable: irresponsible beauty clinics selling bogus treatments at highly inflated prices with no concern for patient safety etc., etc. What actually happened was that a batch of antibiotic used in the culture medium was contaminated with a commensal organism but when this became greatly expanded in culture it led to septicaemia. Tragic indeed, but a very similar thing had happened to a batch of steroid injections for back pain prepared in a facility in the USA and there were multiple deaths. The current count is 63 deaths so far (http://www.cdc.gov/hai/outbreaks/meningitis-map-large.html accessed 20th August 2013). Of course, deaths from an injection for back pain are very different from deaths from the immunological equivalent of colonic irrigation! Or are they?

And so what does the Hong Kong Government do? Standard practice the world over; form a committee and give them time to consider and debate issues and then report when the immediate excitement is all over. The Chairman of the Committee was the Secretary for Food and Health, who happens to be a doctor. The membership of the committee comprised such dignitaries as the deans of the two medical schools, the presidents of the Medical Council and the Medical Association, etc. – altogether an overwhelming representation from the medical professions.

And what were the terms of reference for this committee? Much the same as in the UK, there is a perception that there are a number of unscrupulous cowboys who are making lots of money selling false promises and putting profit before safety and that this is the modus operandi of the beauty clinics, so they need to be controlled (but let us not make it too obvious and look at the private hospitals as well as they have been getting a bit too cocky of late). So the committee has devolved into four working groups looking at specific areas of concern:

- Differentiation of medical procedures / practices and beauty services

- Defining high-risk medical procedures / practices performed in an ambulatory setting

- Regulation of premises processing health products for advanced therapies

- Regulation of private hospitals.

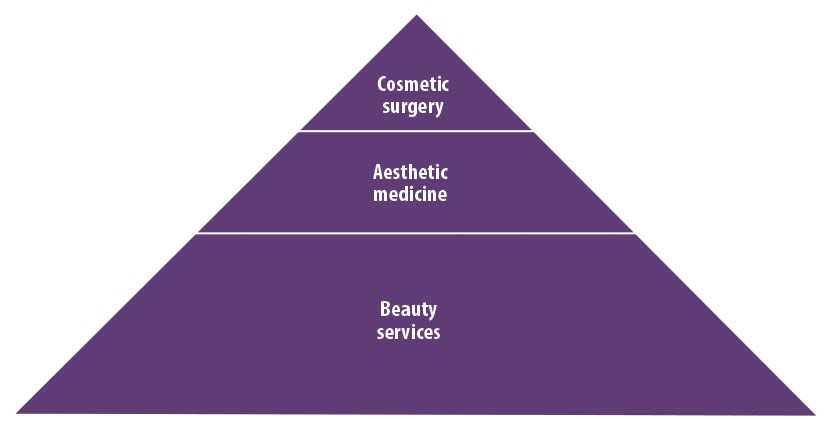

Figure 2: The pyramid can be flattened somewhat to reflect the differing proportions of those seeking treatments in different sectors of the industry, but also to reflect the number of providers in each sector. In Hong Kong there are over 500,000 working in the beauty services sector, a few hundred in the aesthetic medicine field and less than 100 in the field of cosmetic surgery (adapted from presentation by Dr Mary Lam). This is a representation of the numbers of patients / clients served by the various parties in the cosmetic intervention business. In reality there is more overlap and this is where the problems arise. Nevertheless, without looking at the denominator in the risk equation it is just not possible to say whether any practitioners are better than others.

Fast forward to a symposium I held at the Prince of Wales Hospital in Shatin in Hong Kong in June of this year. The theme, which was suggested by our wonderful nursing staff, was ‘In search of Beauty’. My major interest is post-burn reconstruction and in our field we see a major interplay between the reconstructive surgeons, the aesthetic medicine practitioners and the beauticians. I had invited Mr Rana Das-Gupta from Warwick and Coventry to address the topic of Aestheticology (Figure 1).

I had no hesitation in using this opportunity to invite representatives from the medical aesthetics and beauty industries to share with us their perspectives on collaborative working to achieve the best possible outcomes for our patients in terms of reintegrating into society. Doctor May Lam gave a very mature and responsible overview of her perspective of the role of medical aesthetician in what would, in UK terms, be the field of cosmetic interventions. Indeed, there is a numbers game at play and a hierarchical scheme of complexity, which can be demonstrated in a simple diagram (Figure 2).

I also invited Mr Nelson Ip, who is a publisher in the beauty industry and a representative of the beauty sector in the Working Group looking at the difference between medical and beauty treatments. Nelson also gave a very balanced, responsible and concerned overview of the beauty industry and how they see themselves as professionals, with training, experience and a high index of satisfaction amongst their clients. Subsequently, Nelson suggested a Q and A interview for his members to appreciate that not all of the medical profession have blinkered vision. The transcript of the interview follows at the end of this article.

...there is a perception that there are a number of unscrupulous cowboys who are making lots of money selling false promises and putting profit before safety...

The situation in Hong Kong is an unresolved mess and it will remain so whilst certain members of the medical profession try to muscle in on territory to which they have no rightful claim in terms of training, competence, certification and superior results. At the same time, it is important for some of the older (more conservative) members of the medical profession to wake up to a changing world and acknowledge that the beauty services industry does play an important role in the health and well being of many thousands of people in Hong Kong, indeed countless millions worldwide.

Back to the UK and this summer there was great consternation expressed by some about the winner of the UK version of The Apprentice with Lord Sugar, an astute businessman being lured into the trap of thinking offering beauty / cosmetic treatments equals money, money, money! It is a rather interesting reflection on the tendency to egocentricity in socially and / or professionally cohesive groups such as doctors that they expressed such surprise at the outcome of The Apprentice in view of the Keogh Report just a few months earlier. Mark Henley of the British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons suggested the outcome of the show trivialised “non-invasive cosmetic surgery procedures and suggested that the risks of physical and emotional harm were being ignored for the sake of financial gain and entertainment.”

The reality is that probably only a small number of people get worked up about fillers and botulinum toxin and it would appear the great British public doesn’t care who gives fillers so long as they work, are safe and are not too expensive.

...certain members of the medical profession try to muscle in on territory to which they have no rightful claim in terms of training, competence, certification and superior results.

So we have moved from PIP, to DC-CIK to reality TV and there are some interesting themes to pick out; territory, competence, holistic care, conflict of interest, professionalism, accreditation and certification. There are many more to explore; techniques, devices, procedures, materials, as well as blended and overlapping care from a multidisciplinary group, each member of which excels in their field. Perhaps I can finish by quoting myself when I wrote an Opinion piece for our local English language newspaper the South China Morning Post. This appeared on Saturday 13th October, 2012, just a few days after the Government had decided to try and introduce more regulation and control in the Beauty industry:

“The [Hong Kong] public needs to be protected from the greed and lack of professionalism of a minority of practitioners in the beauty and cosmetic industries. At the same time, people need to be protected from false or unrealistic claims in all health- and beauty-related businesses.

“How this can be achieved is another matter. Self-regulation is always a problem with inherent conflicts of interest. Legislation is a cumbersome tool. One way forward would be to bring all relevant stakeholders together to explore common ground and build on that. It can be in no one’s best interest to be regarded as reckless and dangerous.”

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.

Interview between Mr Nelson Ip, Representative of the Beauty Services industry in Hong Kong and Professor Andrew Burd, Professor and Chief of the Division of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong (Rtd).

Do you think it is realistic and reasonable for the government to try to differentiate some procedures as being either ‘medical procedures’ or ‘beauty services’?

It is reasonable but not realistic to try to differentiate between medical and beauty treatments until and unless you take the time to define and determine what is meant by a medical treatment on the one hand and by a beauty treatment or service on the other. To both the professional and non-professional people in the medical and beauty sectors there is probably an intuitive agreement that a medical procedure is one that has the intention of treating and / or curing some deviation from the health of a patient such that the health of the patient is restored. A beauty treatment or service is, however, one that is not necessary for the maintenance of health per se but one that can add to a more holistic wellness of being of a client.

Of course to use such terms as patient and client, health and ‘wellness of being’, require further exploration of meaning, definition and application.

So my impression is that the government’s desire to differentiate between two areas of practice is not for understanding but a political manoeuvre to create a precedent from which control and regulation can further evolve. Such an approach is NOT to be encouraged and I would only support such a strategy if it was undertaken by a completely independent body who are able to define their criteria in a way that satisfies all parties, i.e. those in the medical profession, those in the beauty services, the government and, last but perhaps most important, the public.

Do you agree with the saying that ‘procedures with risks (e.g. hair removal by using laser devices) = medical procedures’?

This is an easy one. This approach is nonsense and could only have been proposed by a very short-sighted member of the medical profession! Risk is part of the human condition. A slight diversion here is to just reflect on the original term the barber surgeons who were ‘medical practitioners’ in medieval times. It was their skill using knives and razors in cutting hair that naturally extended to their selection as a group to cut off injured limbs and bits of flesh from wounded soldiers. I would like to think that we are a little more advanced nowadays and I would never consider giving a lady a perm as being a medical procedure, and yet there is risk involved. Indeed look at the simple hair dryer used in all high street hair salons; this can cause deep burns if used by an untrained person. On this basis should it only be medically qualified people who run hair salons?

Are doctors the only ones qualified to operate energy-based devices or get the related training?

Absolutely not. Again look at nurses, radiographers, physiotherapists, occupational therapists. Thinking laterally, look at train drivers, pilots, firemen, soldiers, there are any number of people out there who are trained to use machines, devices, products that could be immensely harmful if wrongly applied. Doctors are not a separate or special sub species of humanity.

Do ‘aesthetic medicine’ and ‘cosmetic intervention’ exist in reality?

A recurring theme in my responses will be that confusion exists because terms and terminology have not been defined and discussed in a consensual manner. I see aesthetic medicine as a relatively new discipline which is focused on many areas of the physical, psychological and spiritual activity of people who are essentially healthy in terms of disease but have a concern about some deficiencies in their wellness of being. This stretches far beyond the simple focus on botulinum toxin and dermal fillers but must include attention to nutrition, exercise, psychological resilience and spiritual focus. In this respect, yoga, meditation and acupuncture can all create positive improvements in those who engage in regular practice. In this respect I see the effect of the aesthetic medical approach to have an incrementally more significant impact on the recipient than a cosmetic procedure, which is more superficial in impact.

The term ‘cosmetic intervention’ comes from the Keogh report and is defined thus: “operations or other procedures that revise or change the appearance, colour, texture, structure, or position of bodily features, which most would consider otherwise within the broad range of ‘normal’ for that person.”

They have tried to be inclusive but examination of this description or definition reveals fundamental flaws that in effect make this report and its recommendations a cosmetic political intervention but not something that is going to resolve issues of patient safety, consumer satisfaction and a fair and balanced approach to what are an extremely diverse collection of procedures which are, essentially, unessential (for health).

Do medical specialists in the market have sufficient and comprehensive training in cosmetic / aesthetic procedures?

This question is one that troubles me greatly. It is an indisputable fact that certain specialists and their senior representatives are perpetrating an absolute fraud, a deception on the people of Hong Kong. It is a great shame for me that it is the specialty to which I belong which is perhaps the worst offender in this case. I am from the old style British training, before limited working hours, when we followed our boss in the NHS, in the private clinics and operating theatres and were truly trained in the full breadth and depth of what is a wonderful specialty.

Things are different now. In Hong Kong, specialty training takes place in the public hospitals. For reasons that are not entirely rational the Hospital Authority (HA) does not allow cosmetic procedures to be performed on public patients in the HA hospitals. Plastic surgeons in Hong Kong are completing their training and getting their board certification with very little or absolutely NO cosmetic surgery exposure. This deficiency has been the topic of anguished debate by the Plastic Surgery Board in the College of Surgeons, by the specialty-working group for Plastic Surgery in the Hospital Authority and amongst the Society of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons. One major problem is the fixed and inflexible mindsets of certain key players who refuse to recognise that cosmetic surgery covers a spectrum of procedures which do not, as a whole, fall within the exclusive scope of any group of doctors, be they specialist surgeons, physicians or indeed generalists.

Now for some clarification and qualification for the previous statements, which I am confident, will be misquoted!

I have been involved in the training of quite a few of the plastic surgery specialists in Hong Kong and I have watched when they leave the public sector to set up their private practice. Many will go abroad for longer or shorter periods of time, often repeatedly to acquire the knowledge, skills and expertise in cosmetic plastic surgery. So let me say, and I cannot name names unfortunately, that there are some excellent cosmetic plastic surgeons in Hong Kong. Going through the rigorous training in managing trauma, tumour and congenital and degenerative diseases in the public sector have given them skills and an intuitive sense of tissue handling that serves them well when they go to acquire new skills of cosmetic surgery. But as in all specialties there are those who have clumsy surgical hands and erratic clinical judgment that make them difficult colleagues to work with, and so just completion of specialist training does not guarantee the high order competency that we would wish to be associated with all specialists.

A further point is that the dishonesty and deception as elaborated above in the context of plastic surgery training is not an exclusive Hong Kong phenomenon; in the UK there is a certificate of completion of specialist training (CCST), and with that on board the bold and the brave (reckless) new specialist will claim competency in procedures they may never even have seen. We call this in the trade the ‘first facelift phenomenon’. It is a fraud practised in Hong Kong, in Australia and in the UK. And it is one of the reasons I have advocated, in the past, to distinguish between training (based on theoretical knowledge and limited exposure) and competency (based on outcome-based clinical practice) and to continue with our exit exams in Hong Kong after four years of training but not award certification as a fully board certified plastic surgeon for another four years’ time, during which specialists can undertake further hands on clinical training in cosmetic surgery or indeed other sub-specialisations at home or overseas. An idea, by the way, which not surprisingly went down like the proverbial lead balloon.

What do you think we can do to effectively enhance clients / patients’ safety in receiving such services?

a) Education and training.

b) Certification not once but repeatedly over the professional lifetime.

c) Logbooks. With transparency, i.e. open inspection and records of outcomes, using photographic records and also patient assessed outcomes.

But this must be done within a practical and realistic context so that providing cosmetic and beauty services does not become such an onerously regulated process that only those who are well-funded can establish themselves. We need competition but it must be fair. We need advertising but it must be honest.

Last year I explored a tentative proposal of establishing a Postgraduate Diploma Course in Aesthetic Medicine in conjunction with the School of Public Health at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. There was widespread support for the idea apart from a small number of specialist plastic surgeons and dermatologists who could not free themselves from the limitations of a mindset that is determined by, yes, greed. Patient safety before physician profit is a fitting sentiment that the medical profession could well do to promote.

The market is potentially huge and there is room for all, with overlapping and complementary services provided by specialists defined by the Hong Kong Academy of Medicine and the Medical Council of Hong Kong, and specialists defined by common senses and expertise. We need the skills, expertise and unique contributions from the beauty services sector to give affordable, safe and effective procedures to a public that can enjoy the experience and not feel as if they are entering a lottery where outcomes are unpredictable and costs uncontrolled.

To view a response to this article by Lucie Michael, please see the article:

IN RESPONSE TO: From PIP to DC-CIK to the Sorcerer’s Apprentice: a medico-political minefield