The specialty of plastic surgery has roots stretching back centuries. Here HS Adenwalla, renowned cleft surgeon, provides a fascinating account of the development of the median forehead flap.

In the early 1970s a young boy of 16-years-old was brought to me with the soft anterior part of his nose bitten off by a rabid dog. He was already covered by the old anti-rabies vaccine which at that point was made at the Pasteur Institute in Coonoor. I used the classical median forehead flap to reconstruct the nose.

The result of the surgery was excellent and created quite a stir in what was then a small mission hospital in Trichur. The flap was divided on the 14th day and the boy was sent home the next day. The story, however, has a tragic ending, a week later the boy was readmitted with severe headache, fever and convulsions. A diagnosis of post-vaccinal encephalitis was made and in spite of all that we could do the boy died a few days later. A rare complication of the old anti-rabies vaccine.

After this I had reason to use the median forehead flap or the ‘Indian method’ as it was often called on several occasions and I began to search the history of this very useful procedure. I found that its origin lay in antiquity, and could be traced back to the great Indian Ayurvedic surgeon Sushruta.

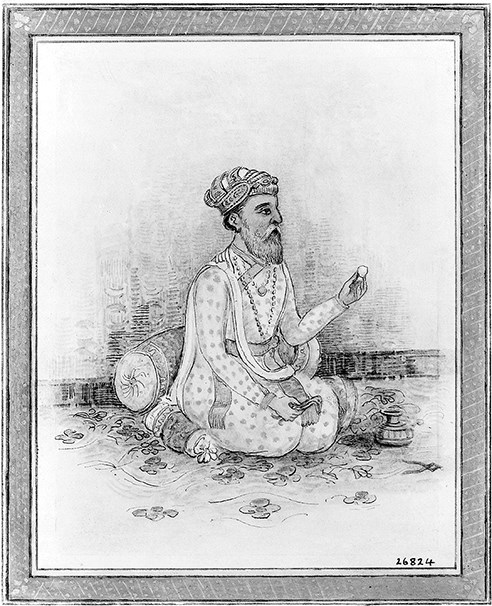

Figure 1: Watercolour portrait of Sushruta. Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

By: H Solomon. Wellcome Images, http://wellcomeimages.org

Ayurveda means the knowledge of longevity and its origin is clouded in legend. It is said that it was founded by Dhanvantari, the God of Indian Medicine. Dhanvantari was to Indian medicine what Aesculapius is to Greek medicine. He is supposed to have risen from the churning of a sea of milk. He was so moved by the sufferings of mankind that he asked to be born as a prince in Varanasi and the gods yielded to his request. He practised the art of healing and after a time retired to live as a hermit in the forest where he wrote the basics of the science of Ayurveda for the benefit of mankind.

Five hundred years BC in an age of peace and plenty there lived a remarkable man called Kashipati Devedasa, a great teacher of the art of healing; long before Hippocrates he enunciated the principle that “Above all do no harm.” This enlightened teacher taught his students only as much as they could assimilate and made them vow that they would not practise anything beyond what he had taught them. He was Sushruta’s teacher, and to him he taught all that he knew and prophesied that Sushruta would one day rise to greater heights and would surpass his teacher. The prophecy came true and culminated in the first written evidence of Ayurvedic medicine, known as the Sushruta Samhita. This, and the Charaka Samhita which came later, are the two massive manuscripts which form the twin pillars of Ayurveda. Ayurveda has no connection with the Vedas written in the Vedic period, but the philosophy of the Vedas must have influenced the science of the “knowledge of longevity.”

Figure 2: The Sushruta Samhita or Sahottara-Tantra (A Treatise on Ayurvedic Medicine).

Source: Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Sushruta was not only a great and versatile surgeon but was also an inspiring teacher. He innovated major operations and created a variety of surgical instruments, and it is said that plastic surgery originated with Sushruta. In days gone by, cutting off the nose was a common punishment in females for infidelity and in males for a variety of offences (indeed it is still continued in India, though not on such a large scale). It is commonly believed that Sushruta was the first to devise the median forehead flap (the Indian method) for reconstructing the nose, but this is not true. Sushruta’s procedure was actually to use a cheek flap. One of his pupils realised that the cheek flap left a bad scar on the face and that the pedicle often kinked, jeopardising the blood supply to the flap frequently ending in disaster. It was this unknown and unnamed student of Sushruta who devised the median forehead flap as we know it today. The scar he said could be easily masked by some of the Indian jewellery that women wore and men could mask it by the religious marking on their forehead. It has often happened in the history of medical science that a major contributor is forgotten or is not recognised.

“It has often happened in the history of medical science that a major contributor is forgotten or is not recognised”

The first public documentation of the ‘Indian method of rhinoplasty’ was recorded in Poona in 1793. A Parsee gentleman by the name of Cowasjee, a bullock cart driver in the English army, was captured by Tipu Sultan’s soldiers in the Mysore war of 1792. His nose and his hand were cut off. His four colleagues suffered the same fate. The man that Cowasjee consulted was not an Ayurvedic physician but a common brick layer or clay potter who had learnt the art from the Ayurveds. Cowasjee and his four associates were given new noses. The clay potter’s surgery was witnessed by Thomas Cruso and James Findlay, both British surgeons serving the Government of the Bombay Presidency. Their graphic description was published in the Medical Gazette and later reported in the October 1794 issue of the Gentlemen’s Magazine. Every step of the operation was described in great detail.

Figure 3: Tribhovandas Motichand Shah.

The story published in the Gentleman’s Magazine was then read by JC Carpue, a 30-year-old surgeon practising in London. He used the procedure for the first time in 1816, thus introducing the ‘Indian technique’ to the West.

The next documentation of interest comes from Tribhovandas Motichand Shah, Chief Medical Officer of Junagadh State in India. His paper ‘Rhinoplasty: A Short description of a 100 cases’, was published by the Junagadh Sarkari Press in 1889. He was a man of the most humble beginnings, coming from a very poor Jain family and working his way through school. People laughed at him when they heard him say that he wanted to be a doctor, for they thought that such a career was beyond his reach. There were then only two medical schools in India; one in Calcutta and one in Bombay, called the Grant Medical College which was affiliated with the Sir Jemsetjee Jejibhoy Hospital. With great difficulty Tribhovandas travelled the 400 miles to Bombay and enrolled himself at the Grant Medical College and obtained the qualification of Licentiate in Medicine (LM). It was the only qualification open to an Indian student at that time. Tribhovandas worked for a spell in the suburbs of Bombay dispensing bottles of medicine. He collected some money in his practice there and then migrated to Ahmedabad and obtained clinical experience in surgery at a private hospital. Over a few years he attracted the attention of the Nawab of Junagadh, who began to take a personal interest in this young doctor who had a flare for surgery. The Nawab induced him to return to Junagadh and appointed him as Chief Medical Officer of the Junagadh State Hospital. It was here that this modest young man blazed a trail in reconstructive surgery, performing 100 median forehead flaps for reconstructing noses in four years and 300 of the same in his short professional life span. A record never to be equalled by any plastic surgeon in the world. The story goes that this volume of work was provided to him by a famous local ‘dacoit’ by the name of Kadu Makrani. This dacoit robbed, raped and cut off people’s noses. Tribhovandas published his work in 1888 in the Indian Medical Gazette, and then a monograph on the subject in 1889. In all these cases he used the median forehead flap; in some cases when he needed more tissue for lining he also used cheek flaps.

Professor Charles Pinto wrote a tribute to Tribhovandas which was published in the journal Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery: “We today must assess this man’s contributions to modern plastic surgery, not only for its intrinsic scientific value but also for the appreciation of the unhappy victims of this nasty brigand chief. There still exists a Gujarati saying “Kadu kape nak, Tribhovandas sande,” the literal translation is “Kadu the bandit cuts off noses and Tribhovandas repairs them.” One must also appreciate his versatility, he did more cataract surgeries, inguinal hernia repairs and caesarian sections than he could keep count of. He wrote books on maternal and childcare. He also wrote books on anatomy, surgery and physiology and a large monograph on Indian medicinal plants. Tribhovandas was no ordinary man and deserves to be remembered as a giant in his field. Dr Shah died at the age of 54 years of coronary thrombosis. He left two massive monuments for posterity: 1) He carved with his own hands 10,000 steps into a mountain face for pilgrims to reach a Jain temple, his personal expression of a deep commitment to his religion; 2) His work in rhinoplasty which was his personal legacy to plastic surgery.”

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME