Cleft lip and palate surgery is a life changing event. In many regards the surgery itself is relatively straightforward without major physiological consequences and the opportunity of making an impact for little risk is highly attractive. Medical missions offer the framework for medical personnel to deliver their skills in a location where need outstrips supply, and it all seems a perfect fit.

However, despite good intentions, medical teams visiting foreign lands to provide services can end in disappointment or even disaster for all concerned. Unfortunately, no ‘try before you buy’ is possible for a surgeon considering joining these missions, and the step to participate requires substantial commitment. Hence, the decision to become involved with this type of work warrants consideration of issues beyond those usually faced in day-to-day practice in the developed world.

This article aims to provide some background, and ‘food for thought’ to enhance the likelihood that the experience will be enjoyable and beneficial for all concerned – a ‘stay out of trouble guide’.

The environment

Outreach surgical care can be delivered either by fitting into an existing hospital framework or temporary platforms of variable independence. The latter essentially creates a field hospital that is able to deliver care to areas of need that are beyond access to local services. Such an environment is by its nature limited in the services it can safely provide, a fact that can impact upon the outcome quality despite the capabilities of the surgeon – this is an important issue to accept [1]. Temporary surgical facilities are by far the most common in the delivery of cleft services in low income countries.

The consistent feature of charitable teams is an environment that is unfamiliar in almost every aspect. Surgeons, often unbeknown to themselves, are creatures of habit and, dare it be said, tend to control their environment, perhaps to reduce variables and ensure reproducibility. For such a surgeon, the mission environment can result in considerable upset and can affect performance. This, in itself, compounds the issue, especially for a surgeon who, on home ground, is well versed in his / her art. In this light, it is prudent for a seasoned mission surgeon to be paired with newcomers to surgical mission work.

In the surgical field hospital one is brought face to face with local ‘need’. The waiting list is gone – replaced by people – people in ‘need’. One can be overwhelmed, both physically and emotionally, perhaps realising for the first time what it means to deliver healthcare on a humanitarian level.

No man is an island – it takes a team.

A week’s work – whiteboard theatre list, with natural tropical airflow.

What to leave behind and what to bring

One of the most common questions asked by new team members is, “What shall I bring?” The answer to this question is both simple and complex: “Bring only the essentials, and also bring all you have – because you will need it.”

For a surgeon it is necessary to confirm what resources are locally available, including those needed to handle unexpected complications, such as bleeding and airway issues. Tangible baggage that is necessary for a surgeon should be pared to one’s personal ‘essentials’ that really make the difference when one is working, e.g. a portable headlight. Other intangible essentials include factors that impact quality of care and ethical considerations [2,3] – do not leave these behind.

Participation in such an undertaking is an opportunity to practise surgery with more medicine. Often local medical services are limited, meaning that for potential patients this may be their first medical examination and, given the population of some countries, rare conditions may present with unexpected frequency. One needs to be on the lookout for syndromes and clinical associations, with a high reliance on astute physical examination. Furthermore, largely due to poor living standards, underlying cardiac and respiratory disease is not uncommon, and particularly in some areas, nutritional deficiencies may be prevalent. As a result, screening assessment looms large in determining safe delivery of care, and for many doctors schooled in the developed world or whose practice is mostly private, there may be a significant re-learning curve. All this plays into prudent decisions of patient selection for the environment.

Entrance to the hospital is through the waiting patients.

Expect the unexpected – cyanotic heart disease.

Of medical missions – humanitarian aid

Following the principle ‘form determines function’, the framework within which organisations work is largely determined by their underlying reason for being. This is the yardstick by which it will be evaluated or judged. If the purpose is the provision of service then it is appropriate to use the term ‘mission’ and evaluation becomes one of efficiency and cost. However, unless one is being competitive, service delivery is not a main motivator for most individuals of these surgical teams. A more frequent motivator and facilitator of these multifaceted arrangements is a willingness to help fellow human beings, without distinction. This is humanitarianism, and the provision of ‘services’ from this stance is humanitarian aid, a term that more accurately encompasses the undertaking, and by which undertakings are evaluated.

Common pitfalls

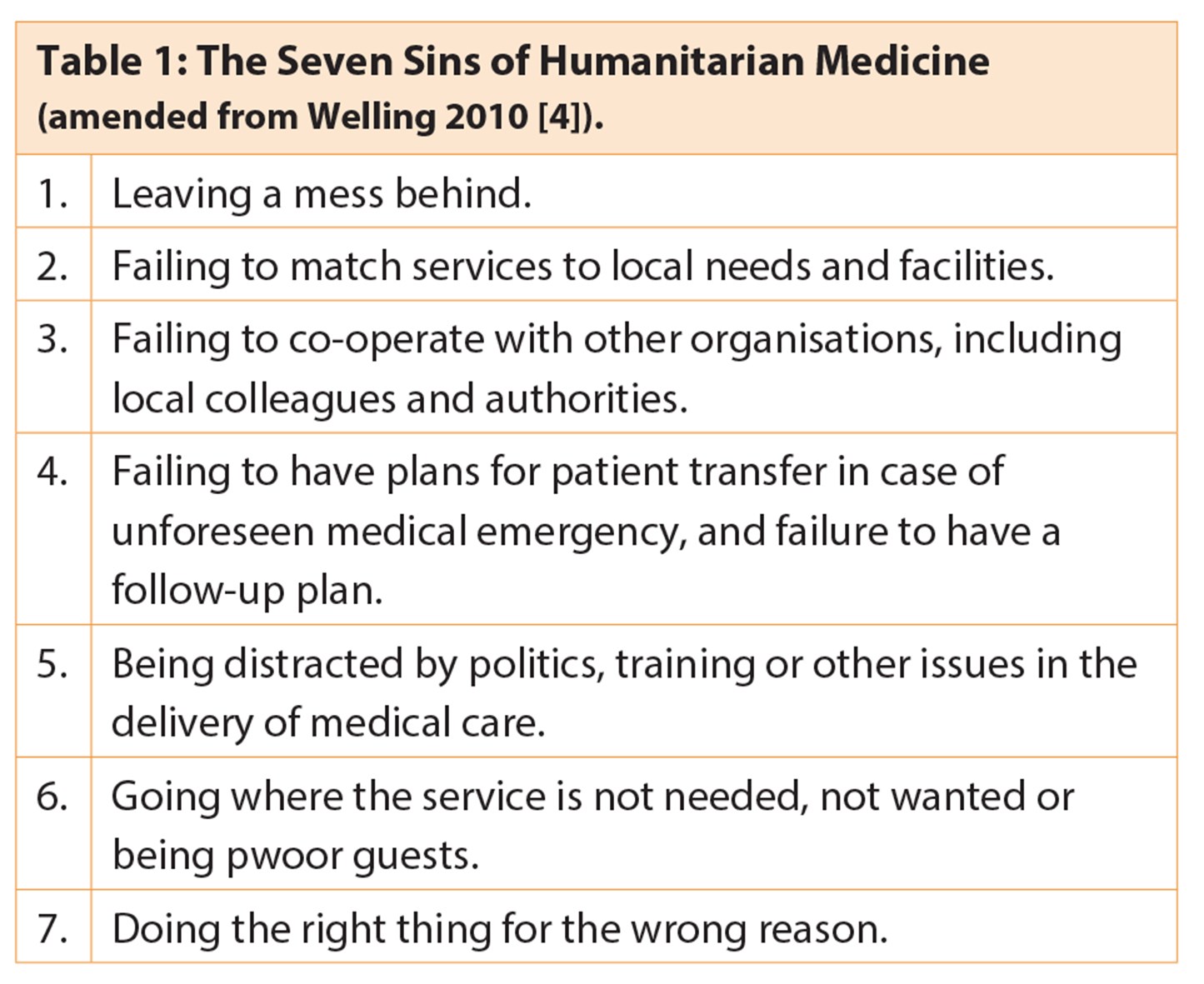

There are multiple definitions of ‘success’ and ‘failure’ depending on the criteria, and the perspective of the assessor – be it organisation or individual. In 2010 Welling grouped the major reasons for failure at an organisational level in humanitarian medicine under the banner ‘The Seven Sins’ (Table 1) [4]. On the whole these represent the ‘lingering bad taste’ that a well-intended team can leave with the host, representing a mis-alignment between the two.

As an individual joining a team, it is easy to assume that these background arrangements have been attended to, and yet this is not always the case. It is therefore useful to have an idea of the prevailing framework with which the international team views the delivery of medical aid and work to ensure that it is appropriate.

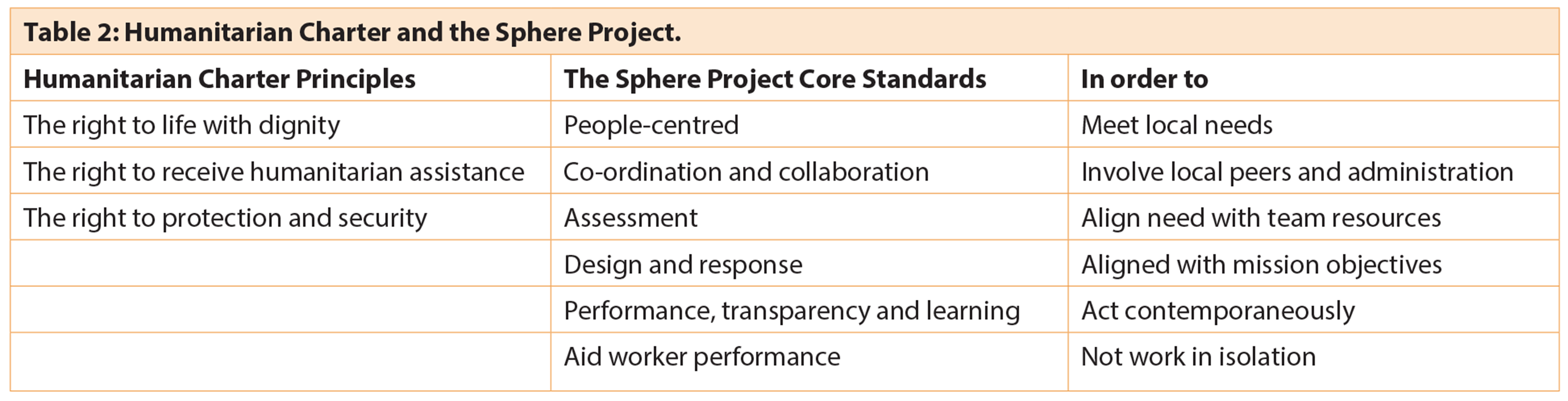

Humanitarian aid – a framework

In 1997 a group of humanitarian non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement initiated the Sphere Project [4], with the aim of improving the quality of their actions during disaster response and to be held accountable for them. Although formulated around disaster or conflict the resultant Humanitarian Charter and Core Standards are based in international law and include process standards that are applicable to the delivery of all medical aid, at the heart of which is the inclusion of the affected population, and processes to enhance quality and accountability (Table 2).

The Humanitarian Charter and its Minimal Standards provides useful guidance when providing medical aid, based as they are on the principle of humanity. Implementation of a globally recognised code of conduct would go a long way to bring the delivery of medical care into an accepted framework of accountability and prevent the ‘Seven Deadly Sins’.

Organisational preparation

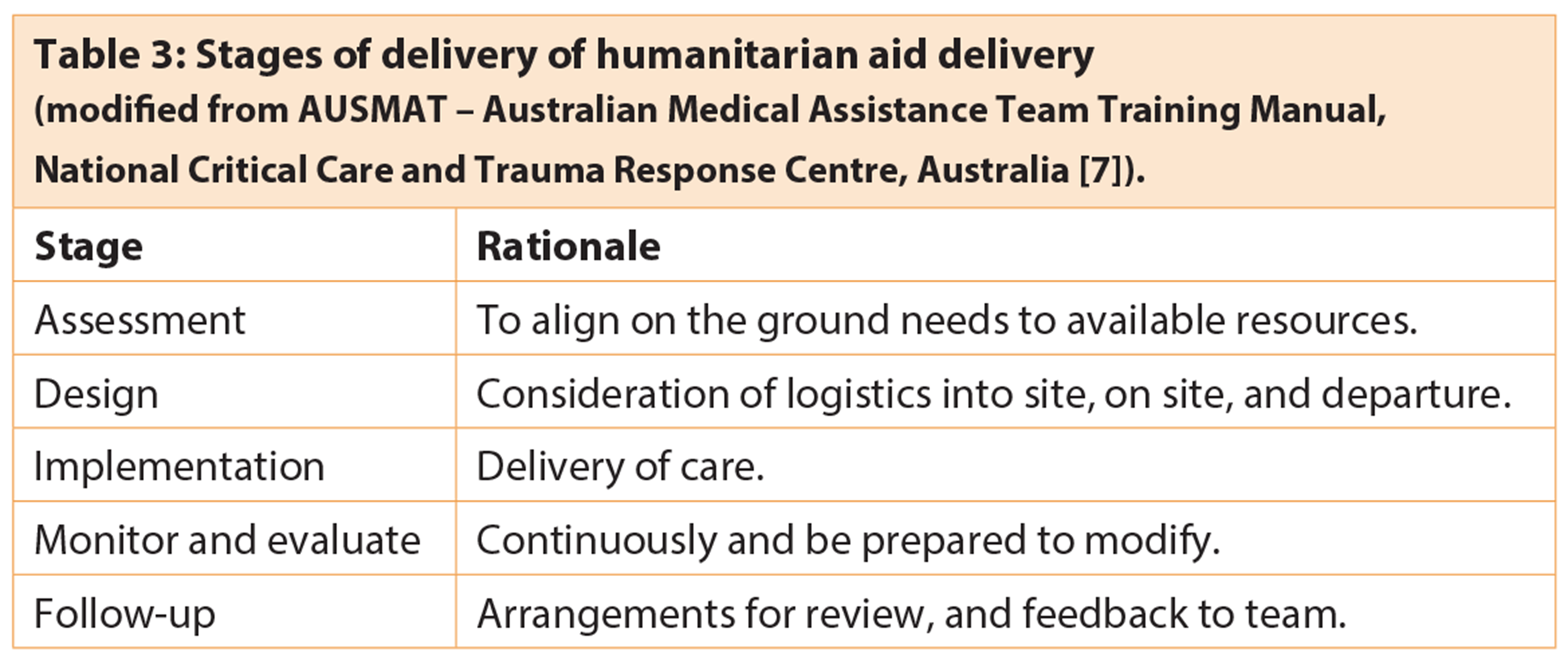

Most significantly, cleft lip and palate (CL+P) teams can be arranged and delivered in a more organised manner than in conflict or calamity [5,6]. As a surgeon, focus is almost habitually on delivery of care, however a significant amount of this preparation is undertaken months prior to the mission. It can be a deflating experience to turn up, full of enthusiasm and willingness to help (after all that is the nature of most healthcare providers) to find oneself almost impotent because of lack of planning and consideration of facilities; those things that most of us take for granted in both our daily lives and our working lives – facilities without which we cannot move into action. A general schema for the roll-out of a temporary aid platform is given in Table 3 [7].

Controversies and cautions

The yardstick by which outcomes are judged is controversial, and there are a number of criticisms made towards ‘fly-in / fly-out’ teams. However, it is salutary to bear in mind that aid is being delivered in an area of need, where sometimes the only choice is between care or no care at all, and while recognising that the highest quality result possible is desirable, this may not be a realistic goal. In such circumstances it is sometimes necessary to apply the concept of ‘best care under the circumstances that cannot be bettered’.

A word of caution – it is common to be called ‘experts’ when providing services, and while it may be justified to call teams and team members this, it is also true that there will usually be local experts, who on their home turf get little recognition. It is tempting to assume this title, as it is often offered with respect, and at the same time it is essential to acknowledge the local expertise, which is often of high calibre.

It can be useful to imagine the roles being reversed – a team of ‘experts’ comes in, operates and leaves. All would agree that is a poor handover; a situation that planning and communication can largely alleviate. A substantial burden to local resources and staff can be the postoperative surgical case load. Appropriate scheduling of cases that will take longer to heal planned early in the schedule, allows complications to be determined and managed, or at least appropriate arrangements made with local staff. Ideally local healthcare personnel, who are familiar with the postoperative care of such patients, can be arranged to review, manage and feedback, while teams with a scheduled return can maintain continued care.

Another criticism heard is the provision of training under the guise of service provision. Those surgeons working in a teaching and training environment will be familiar with embedding these processes into daily work. For healthcare to be sustainable teaching and learning must be continual and part of the framework that includes local and visiting team members.

Conclusion

Despite all the challenges, many surgeons return year-in year-out providing humanitarian aid across the world, and overall this input increases the volume and quality of cleft care [8]. Although the benefits are many, it is also demanding on many levels and the decision to join a team providing surgical services requires individual consideration. It may be that ‘once is enough’ or one may return year after year. Nonetheless, perhaps one of the most salient lessons is that ‘no man is an island’.

Anecdotes from the edge

Approaching the throng of parents and children that filled the undercover basketball court come triage area, all awaiting our arrival, I felt very small and very overwhelmed by the humanity in front of me, full of great expectations. We were outnumbered – just two surgeons, a small team and a few rooms. By the end of the week, we were done. Many families surrounded us, smiling faces and crying eyes. Relief all round. However, potential problems are never far away, and the biggest is airway. During one case, having spent the best part of an hour battling ongoing ooze from a routine cleft lip repair, while wondering what the anaesthetist was doing to make my life so hard, I was relieved to be finished. Midway through the next case, the recovery room nurse came to inform us that our last patient was breathing strangely, and there was a lot of blood coming from the wounds. The operating list was full and this interruption was difficult, however, the nurse was experienced and insistent. Upon review, the patient had stridor and was covered in blood. The lip was inordinately swollen, and even the needle marks from the nerve blocks were purpuric. To make what could be a case report short, it turned out that the child had been declined surgery by other surgical teams on the basis of her proclivity to bleeding and bruising. Realising this was an issue, the parents withheld that information. The diagnosis? Vocal cord haematoma due to an unknown bleeding diathesis. It could have been disaster, and probably would have been if the surgery had been palatoplasty.

Expect the unexpected – bleeding diathesis, vocal cord haematoma – reintubated.

References

1. Shrime MG, Sleemi A, Ravilla TD. Charitable platforms in global surgery: a systematic review of their effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, sustainability, and role training. World Journal of Surgery 2015;39(1):10-20.

2. Chu KM, Trelles M, Ford NP. Quality of care in humanitarian surgery. World Journal of Surgery 2011;35(6):1169-72; discussion 1173-64.

3. Ott BB, Olson RM. Ethical issues of medical missions: the clinicians’ view. HEC Forum: an interdisciplinary journal on hospitals’ ethical and legal issues 2011;23(2):105-13.

4. Welling DR, Ryan JM, Burris DG, Rich NM. Seven sins of humanitarian medicine. World Journal of Surgery 2010;34(3):466-70.

5. The Sphere Handbook Accessed from

http://www.spherehandbook.org/

en/what-is-sphere/

6. Taub PJ, Lin AY, Cladis FP, et al. Development of Volunteer International Craniofacial Surgery Missions: The Komedyplast Protocol. The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery 2015;26(4):1151-5.

7. AUSMAT – Australian Medical Assistance Team Training Manual, National Critical Care and Trauma Response Centre, Australia.

8. Purnell CA, McGrath JL, Gosain AK. The Role of Smile Train and the Partner Hospital Model in Surgical Safety, Collaboration, and Quality in the Developing World. The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery 2015;26(4):1129-33.

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME